It is innately human to wonder about oneself—likely a side-effect of our big brains and our even bigger egos. How much do we need to wonder though? Not as much as you might think. The human origin story is studied exhaustively by palaeoanthropologists and archaeologists. They could tell you about the structure of your spine and they could tell you why you want so desperately to be part of the in-crowd (hint: it has something to do with limited resources and high levels of cooperation). The catch is, they might tell you different things.

It is an indisputable fact that modern humans—Homo-sapiens—came to be through the process of evolution. The fossils make that clear. How we spread across the world, though, and how we define the “height” of civilisation, is an idea much more complicated. Even science cannot exist in a vacuum, and the stories often told about who we are as a species and how we came to be are not immune to the sociopolitical pressures of our modern world.

That does not mean we do not know what we know. What it does mean though is that there is robust and informed commentary to be read outside the Western bubble as well as within it. In short, the mathematics of addition and not division should be used to govern the narrative we accept about the origin of our species. It is, after all, a global story, for which we need a broad coalition of global storytellers.

In our interview series, It Began In Africa, we invite you to sit in conversation with a few of these scientists—they'll tell you a bit about who you are, and more, who we are.

Dr Curtis Marean, in conversation about the issues of human behaviour, explores the ways in which politicians have taken advantage of our evolutionary predispositions and the hope for using them to combat the climate crisis. Dr Marean is a professor and associate director at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University. He is also an honorary professor and international deputy director at the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University, South Africa. Dr Marean's research focuses on the evolution of modern humans and their behaviours.

How would you pose the argument for evolution and the linear evolution of the human species to somebody that was skeptical?

The simplest thing is to have people sitting down with the actual skulls on a table. Even though human evolution is not linear, there are multiple branches that go extinct and so on over time, there is a trajectory that is easily observable when you put the evidence in front of somebody. That's how we do it in the classroom: we show the timeline and the material evidence and we walk them through the material evidence in a systematic way and explain what happened to these branches that eventually end up going extinct. You have to tell that whole story. There are some species like Neanderthals that go extinct but hybridised with modern humans, and we have some of their genes in us—at least Eurasians do, Africans don't. That's a different kind of ending; they go extinct but have snippets of DNA that survive in us. So we really have these two lines of evidence—we have the fossil record and we have the genetic record, and that's increasingly become important.

To communicate the genetic evidence to people you really have to give them the background on genes and how we construct lineages through genes. That's not an easy task—you have to either have the time to give people the background properly or you have to have a public that trusts science. And as we all know, that's a problem—just look at what's happening today.

Is there any trait that we see then that has been impacted by our crossing, years ago, with Neanderthals or Denisovans before Homo sapiens reigned triumphant? Are we able to see that in any physical markers or mental phenotypes?

The answer is yes, and we're learning more and more about that. The first thing that happens is that we identified the genes that come from Neanderthals and Denisovans. Once you identify those genes, you can start to try and figure out what those genes do; that's the sequence. There's a couple of important things that have been seen. One is that some of the genes that are held by Eurasians, some of those genes associated with Lupus come from Neanderthals. It is already showing up that people with significant amounts of Neanderthal DNA are more susceptible to COVID. Tibetans, indigenous habitants of Tibet, have specific adaptations to high altitude which are basically adaptations to low oxygen levels. Those genes seem to have come over from Denisovans. Over time, we're going to learn more and more and more what these genes are that were introgressed into modern humans.

So if we have these pieces of other species, where is the line drawn? Is there a way to truly define species, and, if so, what are the innately human qualities that set our current iteration apart from previous evolutionary episodes?

We used to define species as the fact that they had a reproductive barrier in between them. Generally speaking, different species don't interbreed. But you have to put the emphasis on generally speaking, because occasionally they will, and, in fact, in ecology, there is an entire sub-field that looks at inter-species hybridisation. Normally, hybrids between species have lower fitness than non-hybrids. Normally, hybridisation is not successful, but when you're dealing with humans, hybridisation is a different thing because modern humans almost certainly saw Neanderthals as being like them. A lot of what is going on between them is probably thought out and probably involves quite a bit of aggression, because, when one group is coming into the landscape of another group, it is often a violent interaction. That's probably the context of what happened.

Neanderthals and modern humans are very different anatomically and there's absolutely no doubt that the variation between them skeletally would lead most scientists to call them different species.

And that's the slimmer build and the bigger cranial cavity?

There's lots of characteristics: different shape to the torso, different limb proportions relative to torso size. It's a significant difference.

I read an article you wrote in Scientific American about the MIS6 climate change phase, so selfishly I guess I'm looking for some concrete evidence that human beings are largely adaptable and can adapt to a major shift in the climate. Is there a key lesson that you think we can learn from our ancestors in terms of moving with a changing world, or a lesson that we're failing to learn right now?

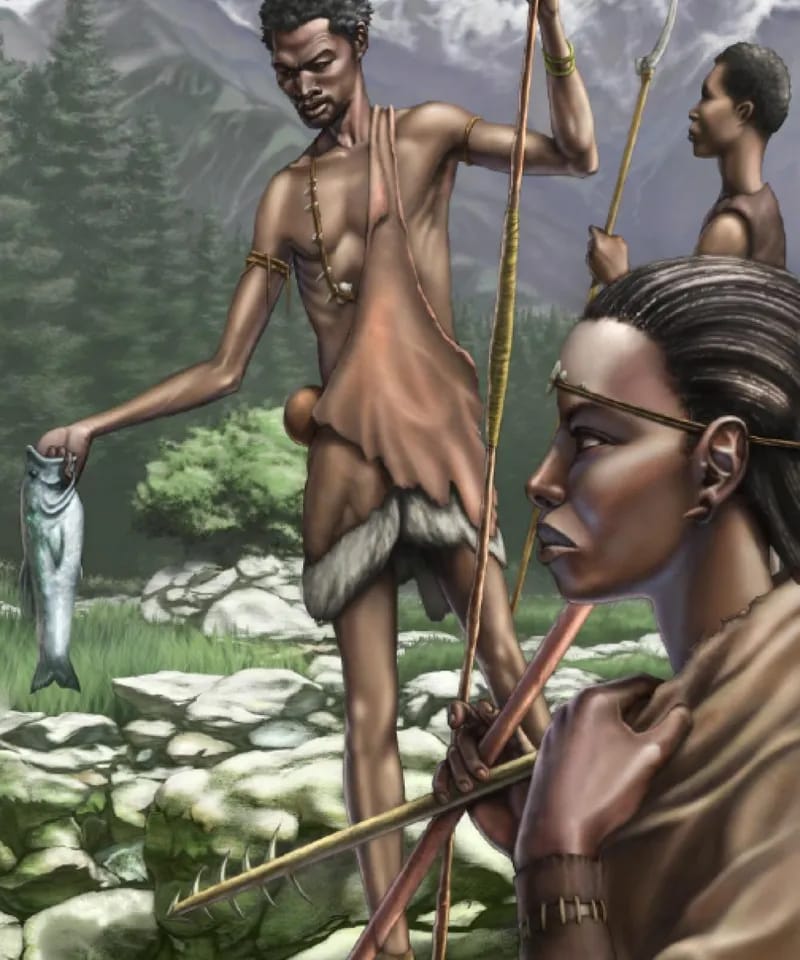

Look, modern humans are super adaptable. More adaptable than any other animal that's ever existed on the planet, and that's because our primary adaptation is culture. Most animals adapt to changes in the environment through natural selection and physiological and anatomical changes, but those happen very slowly, and humans adapt through cultural shifts, technology and so on. But the thing to remember is that 190,000 years ago when Marine Isotope Stage 6 begins—which is a significant glacial phase—humans are hunter-gatherers, they are not dependent on domestic plants and animals. A hunter-gatherer can change its food selection, it can change its hunting behaviour, it can move to get out of the way of environmental catastrophe, but we don't have those luxuries. We are tied to very specific, quite narrow set[s], of foods. If those foods go down in productivity, you're looking at tens of millions of people dying. It's because we live at such high population densities, so we don't have the ability to adapt as easily as hunter-gatherers.

I think that climate change is going to be a catastrophe and we're already seeing some of that. Sea level rise alone is going to displace hundreds of millions of people. Where are they gonna go? Where are the people of Miami going to go? Don't buy land in Miami; it's going to be underwater. They're already having high tides on a regular basis running through main street. If I remember correctly, the estimate is 40 percent of the world's population is in the space that we expect high sea level to eventually flood. Because we live at such high population densities, the challenge to our adaptation is going to be enormous.

The out of Africa theory and the way we talk about the evolution of the human species—do you think that conversation is influenced by sociopolitical or socioeconomic factors at all?

In the sense that humans are emotional organisms, so all scientists are emotional organisms with prejudices and biases and all that baggage we carry with us. So there's no doubt that particularly when we're talking about the human sciences—anthropology, sociology, history and so on—it's fraught with potential bias, but we work hard to use the principles of scientific method to eliminate as much bias as we possibly can.

I have a second article in Scientific American that tells the story of how the switch to coastal resources which are dense and predictable triggered the evolutionary selection context for very high levels of cooperation, which we see among modern humans, which is a unique characteristic of our species—high levels of cooperation with unrelated kin. We're the only species that does that. But, it argues that that particular evolutionary move happened in conditions of warfare and then gave modern humans the ability to rapidly expand out of Africa at the expense of all other competing species like Neanderthals and Denisovans. That's a general theory I've constructed for what I like to call the great human diaspora which is the explosion of modern humans out of Africa into every corner of the planet, now continuing into space. Scientific American, I think, titled it the most invasive species because we are, and we use our cooperation and our technology to be invasive, move into any area we want to move into, and then we fight over those new areas we move into. And unfortunately, Neanderthals and Denisovans were in our way.

So the colonial spirit is genetic? Conquering and dispersing and fighting over that land is genetically a part of the way we cooperate with one another?

Look, I wouldn't say that we have a genetic predisposition toward colonisation; that's a little bit specific. I would say that we have an evolved emotional psychology to cooperate at very high levels with unrelated kin and, oftentimes, in situations of conflict against outsiders, the “other”. That evolved emotional psychology—that's a psychological machinery that's evolved in our cognition, and in an emotional context, ends up being exploited by demagogues like Trump or other people who look for divisions based on race and religion and economic status and so on. They manipulate it and unfortunately, most people are completely unaware of what's being done to them. Colonisation is a bi-product of that. So when resources get low, what do they do? They take land and figure out reasons why that's okay.

So it's not the predisposition itself that is a political thing, but it can be warped into that by people to take advantage of it?

Yeah, shaped and manipulated and the people who do it don't even need to know the science behind it; they just need to know human nature. We've seen it again and again through history. Cooperation has a dark side, and it has a light side. We need to cooperate at very high scales to confront climate change. We have yet to find the leadership who can lead us there in the United States; let's hope that this new leadership can do that.

There's blame on both sides, and we have to figure out a way to understand that people are going to differ a lot on these opinions, but we have to rally around the big problems. And figuring out how to, in a sense, nudge the psychology of people in that direction is not easy.

One of my primary research interests is the evolution of cooperation. I think we're making important progress in science on this from multiple fields. But it hasn't bled over into policy particularly well.

I want to talk for a second about the out of Africa theory which is one of the few phrases from the scientific world that has passed over into common language. Do you think that means people understand it at a basic level? If they don't, what makes you bang your head against a wall and say, “That's wrong, I wish you could understand it this way.”

Most people who accept evolution seem to have some basic knowledge of the out of Africa theory because most people who accept evolution do at least some reading in general science literature, and the advances happening in our field are constant. They know the basics; they might have the dates wrong, but that's okay.

We talk a lot about genetic inheritance of physical traits and the evolution of anatomy, brain size got bigger and bipedality evolved, but it's a different thing to talk about the evolution of behavioural traits—emotional psychology and stuff like that. Yet, behaviour is under natural selection just like anatomy. A lot of that I think has to do with the history of people trying to argue that [there are differences between] races—and science accepted long ago that races don't exist the way that they were defined—but people have in the past argued for differences between the races in intelligence and stuff, so there's been this complete rejection of the idea that behaviour and so on has a genetic component to it, so we don't really talk about those things.

For example, the proclivity to cooperate. Modern humans have a proclivity to cooperate with unrelated individuals. That's not just learned by infants, it's evolved. It's an emotional psychology that has a machinery behind it, and our policies should be informed by that. Unfortunately, we don't seem to be at that level yet, but if we could get to that point, I think it would help us make some progress. If we could accept the fact that some negative emotional proclivities that humans have are genetic, we can also figure out ways to not trigger them. There's lots of evolved patterns of human behaviour that we overcome with culture, norms and so on. We just need to kind of start with science.

I hadn't ever thought about that.

The reason you haven't thought about it is we just don't talk about it much. It frightens people to think about it and talk about it because of the history. For example, cooperation is an evolved feature, therefore there are certain triggers that must cause responses of cooperation, but there are also triggers that cause things like out-group bias (negative categorisations, feelings, or ideas about people who are not part of our ingroup). Well, if we understand the evolutionary characteristics of those, we can figure out policy to enhance cooperative behaviours and to dampen down things like our group bias. But if we don't accept the evolutionary characteristics, then we're just gonna be floppin' around.

Nelson Mandela is a hero of mine. I have a long history in South Africa, of research there and spending a lot of time there. He seemed to have an intuitive understanding of quite a bit of this, and I'm not quite sure how he got that. He had these ethnic groups in South Africa that absolutely hated each other. Afrikaners, which are Whites of Dutch ancestry and most of the African people. Yet he came up with this amazing strategy to get them to rally around the rugby team to win the world rugby cup, and that brought people together at a crucial time when tension between them had to be dampened down. So in reality, what he was doing was triggering between-group altruistic behaviours by, in a sense, distracting them toward rallying around a team—it was just absolutely brilliant, and it fits everything we know about evolutionary theory applied to behaviour. How he figured it out I have no idea; just a genius person.

If you're inducting fossils or findings into the human origin story hall of fame, and you can only choose five, which are those really important ones?

Well obviously, the origins of bipedality is one of those. That happens at least four and a half, five million years ago, maybe longer. That's game-changing.

Then I would say the shift to technology as our primary adaptation, and we're very actively researching that question now, so I can't give you a date. But the thing to remember is that almost certainly the origins of technological adaptation predate the first stone tool technologies; those technologies could have been wood, bone and so on. We really need to figure that out.

Those two are really crucial, and I think the evolution of bipedality and the shift to a technological adaptation sets up the selection suite for increasing brain size. You now enter this kind of feedback loop where, as hominins increasingly shift toward a technological adaptation which, in my way of seeing things, evolves into the cultural adaption, there's strong selection for increased intelligence and cognition. You can't really put a date on the cognition thing because it happens slowly over a long period of time. Cognition is co-evolving with technology.

The third is the evolution of advanced cognition in humans.

Then I would put as the fourth—modern humans have a very unique special form of social learning where we focus on the process of social learning and replicating that process in high fidelity. I don't know if you have much experience around kids; I have two that are both in college now, but really little kids are obsessed with making sure that the process of what they're learning is always replicated. Like if you tell them a story that they love to hear, and then two days from now you tell them that same story but with a slight change, they'll correct you and they'll say go back all the way to the beginning and get the story right. Modern human children are obsessed with a slavish reliance on copying processes, and what that allows us to do is replicate the process of the production of culture in high fidelity. I know it's a complicated thing but it's absolutely the foundation of culture and technology. No other animal learns that way.

Modern human children are born expecting to be taught and expecting replicate process at high fidelity and if they don't get that, terrible things happen in their upbringing. So the evolution of that very special form of social learning is the fourth thing that I would argue is most important.

And then the fifth thing is the evolution of hyper-pro-sociality. Really high levels of cooperation with non-kin. Now, if there was a sixth one that you would fit in there somehow, I would say the shift to being a committed omnivore. Hunting and eating meat and so on; that's important. I used to think that was the number one thing, and I've been convinced over time that it's important but it's not the biggest one. I've replaced it with social learning.