Note: This piece is fictional and is part of our satire section, A Reflective Laugh. Many of our pieces are inspired by real-life experiences and ideas submitted by our community, using satire to explore social and environmental issues. Through humour and wit, we aim to provoke thought, spark conversation and bring awareness to the complexities of the world around us.

Walter Wallsup has spent most of his life perfecting the art of self-sufficiency. While others invested in their pension plans, Wallsup invested in an air-tight emotional vault that no one could penetrate. To him, being self-sufficient isn’t just a lifestyle choice—it’s a survival strategy. He refers to himself as an “emotional minimalist,” holding onto only what’s absolutely necessary and tossing out the rest, especially when it comes to relationships.

In the harsh and unpredictable world of early humankind, survival wasn’t just about physical prowess, it was also about social bonds. Different environments and circumstances called for different strategies. For this reason, even in those early days, humans developed a range of attachment styles, each suited to a specific set of challenges.

“Secure attachment was like the social glue that held early human groups together,” explains Dr Sara Floresiensis, an evolutionary psychologist who studies the origins of human behaviour. “When resources were plentiful and danger wasn’t imminent, forming close, reliable bonds made perfect sense. It ensured cooperation, shared resources and protection for the young and vulnerable. These were the people who built strong communities, who thrived on interdependence.”

But life wasn’t always so accommodating. There were times and places where forming attachments could be a liability rather than an asset.

“In more unstable environments, where threats were frequent and resources scarce, it wasn’t always advantageous to be attached,” Dr Floresiensis continues. “In those situations, an avoidant attachment style could actually be a survival advantage. It kept individuals focused on their own survival, unencumbered by the emotional weight of losing loved ones or being tied down in a high-risk area.”

This divergence in attachment strategies allowed early humans to adapt to a wide range of environments. Secure attachment flourished in stable, cooperative settings, while avoidant attachment provided a way to stay emotionally resilient in more volatile circumstances.

“It wasn’t just about the environment, though,” Dr Floresiensis points out. “Individual upbringing played a huge role. Children who had consistent, nurturing care from their caregivers were more likely to develop secure attachment styles. They learned to trust others and to expect that their needs would be met.

“However, in more precarious situations where caregivers were stressed, absent or inconsistent, children often developed an avoidant attachment as a way to cope. They learned early on that relying on others might not be safe, so they became self-reliant.”

Wallsup likes to think of himself as a product of these early survival strategies. A descendant of those who had to prioritise self-sufficiency over connection. He sees his avoidant style as a badge of honour, proof that he’s carrying forward the instincts that kept his ancestors alive.

“It’s like my brain is saying, ‘Trust no one, depend on yourself and you’ll survive,’” Wallsup explains. “Why get attached when you can just ghost? My ancestors didn’t survive sabre-toothed tigers by exchanging mixtapes. They were too busy inventing the wheel, not writing love letters. My family tree is basically one long history of people who would rather outrun a mammoth than commit to a date night.”

But while this strategy might have served Wallsup’s ancestors well in the wilds of prehistory, it’s not winning him any points in the modern world.

“The problem is, Walter’s stuck in a survival mode that doesn’t really fit today’s world,” says Wallsup’s friend, Mark. “Back in the day, maybe it was useful to keep your distance, but now? Secure attachment is where it’s at. That’s what helps people build strong, lasting relationships. And let’s be honest—Walter’s missing out because of it. Sure, he’s prepared for the next Ice Age, but he’s missing out on the pleasure of debating the correct way to load a dishwasher.”

Secure attachment: the human superpower

While avoidant attachment might have been useful in certain contexts, secure attachment is often seen as the best one in today’s world—for good reason. It’s not just about being comfortable with closeness; it’s about the resilience and flexibility that comes with knowing you can trust and rely on others.

For early humans, secure attachment would have been invaluable in stable communities. It facilitated cooperation, ensured the survival of the group’s young, and created a sense of belonging and mutual protection. Those with secure attachments were likely to thrive in cooperative environments, where trust and teamwork were essential for survival.

“People with secure attachment styles tend to navigate life’s ups and downs more effectively,” Dr Floresiensis says. “They have a support system they can rely on, which helps them manage stress, recover from setbacks and enjoy richer, more fulfilling relationships. Secure attachment doesn’t mean you’re dependent. It means you’re interdependent, able to give and receive support in a balanced way.”

“It’s a bit ironic,” says Sarah, a former girlfriend of Wallsup. "The traits that would have made him a survivor in a more chaotic time are the same ones that are holding him back now.”

As Wallsup grapples with the realisation that his survival instincts might be outdated, he’s beginning to see the benefits of secure attachment—though old habits die hard.

“I get that secure attachment is the way to go," Wallsup admits. "But it’s tough to rewire something that feels so deeply ingrained. My ancestors survived by keeping their distance, and that’s what’s been passed down to me.”

His friends are hopeful that Wallsup will eventually find a way to balance his innate self-sufficiency with the modern need for connection. They believe that if Wallsup can tap into the potential for secure attachment, he might finally find the emotional fulfilment that’s been eluding him.

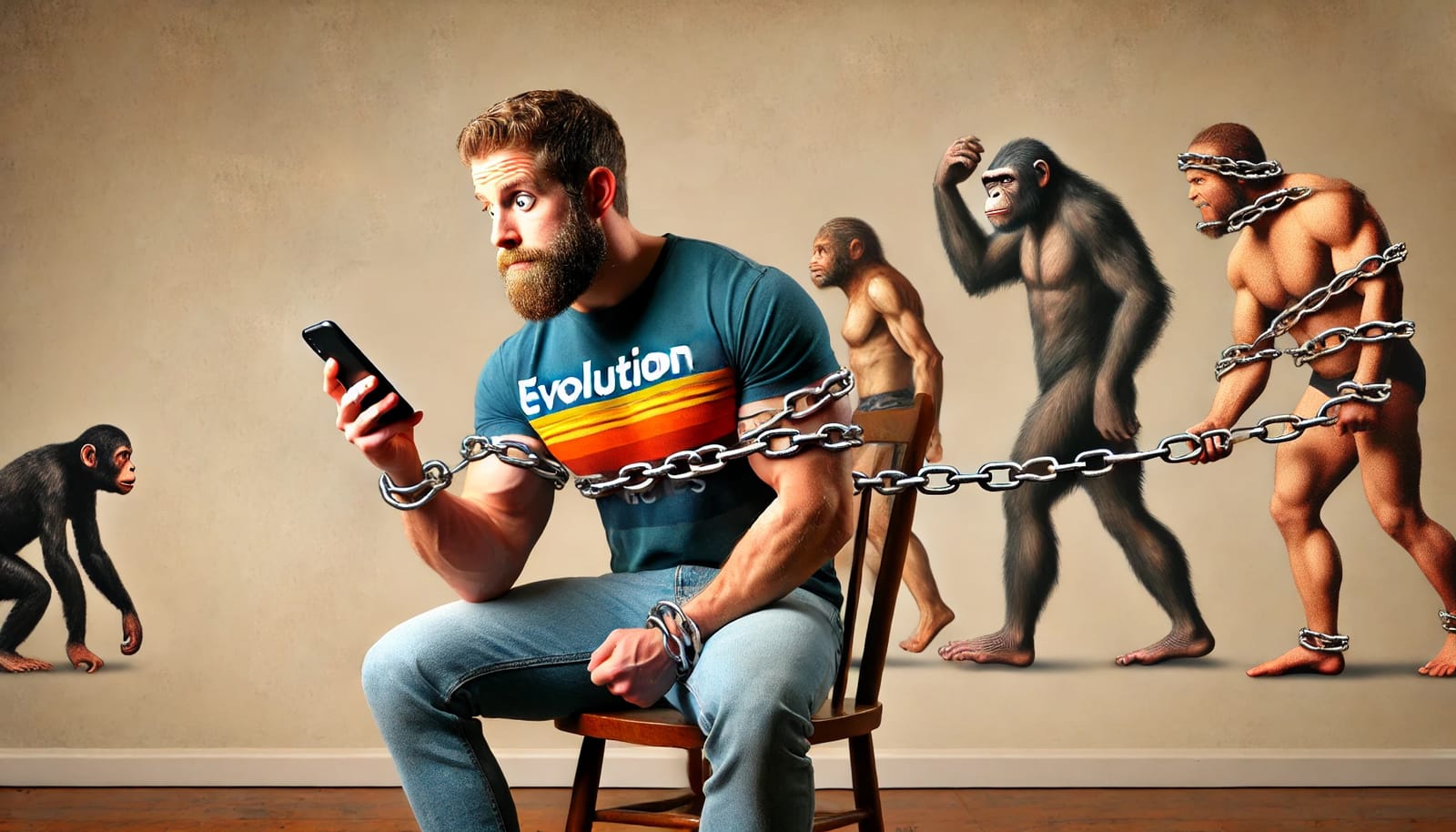

Breaking free: evolution isn’t destiny

For much of his life, Wallsup has seen himself as a prisoner of his evolutionary inheritance, bound by instincts that were created in a world vastly different from the one he inhabits now. But as he reflects on his experiences and the advice of those who care about him, Wallsup is beginning to realise that he doesn’t have to be a slave to those ancient forces.

“I’ve been using evolution as a crutch,” Wallsup confesses. “It’s easy to say that I’m just following my instincts, but that’s not the whole story. The truth is, I have a choice. I don’t have to be stuck in survival mode. I can learn to trust and connect, and to embrace the kind of attachment that works in today’s world.”

While evolutionary forces have shaped the foundations of human behaviour, they don’t dictate the entirety of our lives.

“We’re not just products of our environment or our genes,” Dr Floresiensis says. “We have the power to shape our own paths, to choose how we want to live and what kind of relationships we want to build. Evolution might have given us a starting point, but it doesn’t have to determine the outcome.”

With this new perspective, Wallsup is slowly beginning to explore what it means to break free from his evolutionary chains.

“Maybe I don’t have to be the lone wolf anymore,” Wallsup says. “Maybe it’s time to try something new. After all, if my ancestors could cross entire continents without GPS, I can probably figure out how to reply to a text message without needing three days and a detailed escape plan.”

As humans, we have the ability to learn, to change and to build the kind of lives—and relationships—that work for us in the here and now. Evolution might have brought Wallsup to where he is today, but it’s his choices that will determine where he goes next.

SUBMIT TO OUR SATIRE SECTION

Kia ora, yá'át'ééh, hola, tânisi, namaste, marhaban, nǐ hǎo, olá, zdravstvuyte, konnichiwa, sat sri akal!

We are always looking for new ideas and experiences and would love for you to submit to our "A Reflective Laugh" section. We seek content that tackles social or environmental issues with a hefty dose of satire. Social issues can range from period poverty and world hunger to tongue-in-cheek takes on the human condition and our place within the world.

If you have an experience you wish to share anonymously, this section is the perfect platform. You may choose to add your own byline or keep the piece anonymous—it’s entirely up to you. We can either write about your experience on your behalf or you can submit your own work. Our goal is to make the process as easy as possible for you.

Please email editor@thelovepost.global with the subject line "A Reflective Laugh" and we'll send a submission form your way!