The name Bibha Chowdhuri is practically unknown in the world of physics—not unexpectedly for a field that is notorious for its lack of diversity.

Historically, women’s achievements in science often remained in the shadows of the men who led them. Chowdhuri’s story, despite her determination and her achievements, is no different.

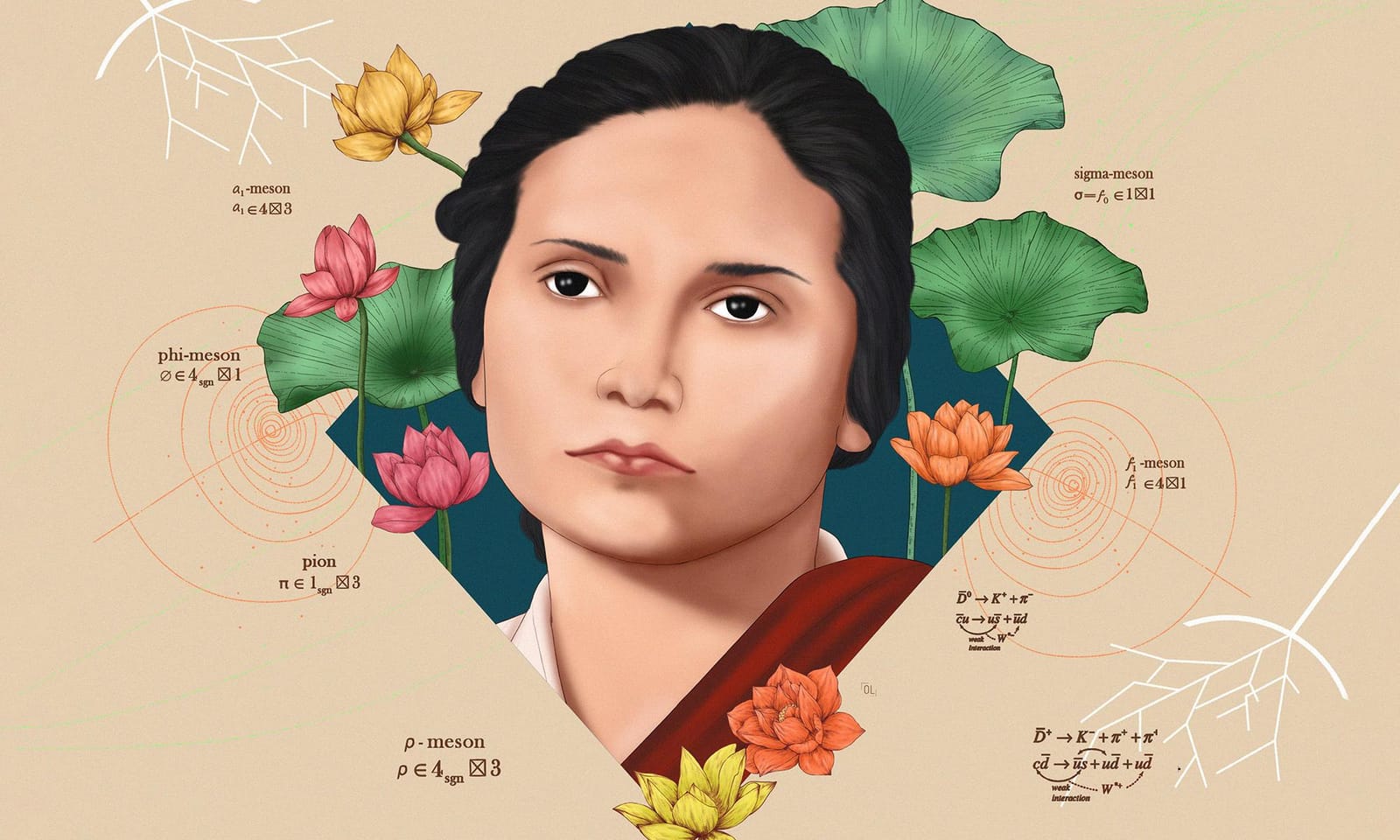

She was the first woman particle physicist in India and made significant strides in the study of cosmic rays and the discovery of mesons. But she was virtually unknown until recently. She was never elected a fellow in any of the Indian academies of sciences and was mostly discussed only in relation to the achievements of particle physicist Debendra Mohan Bose (or D. M. Bose as he’s commonly known) whose research group she was part of.

In her biography A Jewel Unearthed: Bibha Chowdhuri—The Story of an Indian Woman Scientist, authors Rajinder Singh and Suprakash C. Roy write that she “continues to be a forgotten heroine of Indian science.”

Not much is known about her and what we do know is through the accounts of a few people who knew her personally. Her biographers Singh and Roy took great pains to collect information on her and in their book explain that the reasons for her invisibility are manifold: “Bibha Chowdhuri took up research at a time when the number of women in India involved in active scientific research, and that too in experimental physics, was very small.”

Chowdhuri was born in 1913 in Kolkata, the capital city of the state of West Bengal. She was the third of six children, five girls and one boy; her father was a doctor named Banku Behari Chowdhuri, and her mother was Urmila Devi. Her mother’s family were devout followers of Brahmoism, a reformist religion with a doctrine that rejected polytheism, rituals and the caste system, contrary to Hinduism from which it broke off. The Brahmo Samaj, or the society of Brahmo, held progressive and liberal social and religious ideas and put righteousness at its core—its founder Debendranath Tagore declared it “the freedom of reason from the bondage of ancient spiritual authority.” It also promoted education, especially among girls and women.

This kind of upbringing may have been the source of Chowdhuri’s razor-sharp focus on her career, especially since the India outside her home was in sharp contrast to the ideals she lived by. In pre-independent India, the pursuit of higher education among women was almost non-existent; women were expected to marry young, have children and be supportive wives to their husbands. On the occasion that they challenged the norms and prioritised career over family, they were—at best—discouraged, their abilities underestimated and their achievements undermined. Chowdhuri’s personal resolution combined with her progressive household no doubt gave her the freedom to pour herself into her work, which was a rare privilege for most Indian women of her time.

First career milestones and the missed Nobel Prize

In 1934, Chowdhuri joined Calcutta University to pursue a master of science degree in physics. She was the only woman in her class of 24. She graduated in 1936 and became the third woman to have received a postgraduate degree in physics from the university. After graduation, she continued at Calcutta University to conduct research under physicist D. M. Bose. This was an important milestone in Chowdhuri’s career as when she first approached Bose with her interest to join his research group, Bose shooed her off saying he didn’t have any research projects “suitable for women.” Nevertheless, she convinced him to accept her.

This aspect of Chowdhuri’s journey draws parallels to many of her female contemporaries. The most notable of examples would be Kamala Sohonie who, on the basis of her gender, was refused admission to the Indian Institute of Science’s master of science program by India’s first Nobel laureate in physics C. V. Raman, who accepted her only after she went on an indefinite strike outside the institute. Sohonie went on to become India’s first woman to receive a PhD and made important contributions to the field of biochemistry.

The condition of women in science was no better in the West. Astrophysicist Cecilia G. Payne was the only woman student under the famous British physicist Ernest Rutherford, who was known to humiliate her in front of the rest of his students at the beginning of every lecture.

Astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell, the first person to discover pulsars (rotating neutron stars) is another person worth noting. In 1974, her supervisor Anthony Hewish received the Nobel Prize for the discovery but she wasn’t given a single credit. Plenty more examples can be found in the bowels of history, as well as in the present day, especially those involving women of colour.

In 1938, Chowdhuri, along with Bose’s other research students, moved to Bose Institute in Kolkata when D. M. Bose became its director. Chowdhuri worked there until 1942, and it was during that time that she made major contributions to the discovery of a type of subatomic particle known as the ‘meson’ (the heavier sibling of the electron). Chowdhuri and D. M. Bose used photographic plates to detect mesons and published three papers on this in the famous science journal Nature. However, the lack of resources to acquire more sensitive photographic plates during World War II led them to abandon the pioneering project.

Unfortunately for them, seven years later, the English physicist Cecil F. Powell, equipped with sensitive photographic plates, used the same technique as Chowdhuri and Bose to detect two different kinds of mesons known as pions and muons and won the Nobel Prize in physics for his discoveries. Had Chowdhuri had access to better facilities, she may have become the first Indian woman to win a Nobel Prize. It remains a title yet to be achieved.

Perhaps the only other story that is more unfortunate than Chowdhuri’s was that of her peer, Austrian physicist Marietta Blau, who was the original developer of the photographic plate technique used by Powell to detect mesons. Being Jewish, she was forced to leave her home institute in 1938 to escape persecution by Nazis, thereby being cut off from the mainstream of physics and possibly from a shared Nobel Prize with Powell. Blau was exceedingly modest and did not look for acclaim for her achievements, much like Chowdhuri, as Singh and Roy write in A Jewel Unearthed. Though Blau’s achievements were later studied and well-documented, Chowdhuri’s contributions remained obscure as she “did not have friends or colleagues who could highlight her scientific achievements.”

In search of greener research pastures

According to Singh and Roy, the lack of resources at Bose Institute prompted Chowdhuri to leave Kolkata and go abroad to pursue her PhD. In 1945, she joined experimental physicist and to-be Nobel laureate Patrick M. S. Blackett’s cosmic ray research lab at the University of Manchester. This was a time when cosmic rays—subatomic particles that travel through space at the speed of light—were a booming research topic and Blackett spearheaded their detection using detectors called cloud chambers.

It was during this period that Chowdhuri was for the first time acknowledged by the news media for her contribution. In an article by a local newspaper The Manchester Herald titled ‘Meet India’s New Woman Scientist: She has an eye for cosmic rays’, reporter Bridget Maxwell wrote that Chowdhuri studied the “extensive air showers caused when cosmic rays enter the earth’s atmosphere from the interstellar spaces” and that “Miss Chowdhuri is trying to discover the how, why and wherefore of this process.”

In the interview, Maxwell asked Chowhuri why she decided to specialise in physics, to which Chowdhuri simply replied, “I followed my inclination.” Chowdhuri also expressed to Maxwell her thoughts on the state of women in physics: “It is a tragedy that we have so few women physicists today. In this age when science, and physics particularly, is more important than ever, women should study atomic power; if they don’t understand how it works, how can they help decide how it should be used? I can count the women physicists I know both in India and England, on the fingers of one hand."

In 1949, she returned to India and continued research until 1957 at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, now a leading institute at the frontiers of Indian science. She then spent a year in the United States at the University of Michigan. Not much is known about her time there but one of the university’s records shows that she was paid a stipend of 2500 USD for her position as the Physics Department Visiting Lecturer.

Following this role, she returned to India and joined the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad, in the state of Gujarat. During these years she led remarkable projects in particle and high energy physics. The renowned Indian plasma physicist Dr Yogesh C. Saxena was Chowdhuri’s PhD student at the lab, and he described her as being a good teacher who took great care in guiding the scholars she supervised: “At that time there was a feeling in the research scholars at PRL that she was a tough person to work with, which turned out to be totally misplaced as I discovered during my work with her for [the] next several years.”

In the 1960s, she took voluntary retirement from the Physical Research Laboratory and moved back to her home town in Kolkata. There she continued her research in high energy physics by collaborating with various institutes and participating in conferences. She actively held on to her passion for research till her last breath in 1991. We know this because of a paper she authored and published in the Indian Journal of Physics in 1990.

Maxwell wrote in her Manchester Herald report that she was certain Chowdhuri would “try to persuade more Indian girls to follow in her own distinguished footsteps.” Sadly, this prophecy could not be fulfilled as Chowdhuri’s grit, dedication and contribution to the world of particle physics, and physics at large, remained unacknowledged during her lifetime and for the many years that followed. However, recent efforts to revive her story, especially by her biographers Singh and Roy, has resulted in more people in India and beyond learning about her life and contributions. In 2019, she was honoured by the International Astronomical Union who named a white yellow dwarf star after her. “Bibha” is located 340 light-years from Earth in the Sextans constellation and forever seals Chowdhuri’s once forgotten place in history. In the male-dominated field of physics, her legacy will continue to serve as inspiration for many starry-eyed girls and women to follow their inclinations no matter the obstacles.