It is innately human to wonder about oneself—likely a side-effect of our big brains and our even bigger egos. How much do we need to wonder though? Not as much as you might think. The human origin story is studied exhaustively by palaeoanthropologists and archaeologists. They could tell you about the structure of your spine and they could tell you why you want so desperately to be part of the in-crowd (hint: it has something to do with limited resources and high levels of cooperation). The catch is, they might tell you different things.

It is an indisputable fact that modern humans—Homo-sapiens—came to be through the process of evolution. The fossils make that clear. How we spread across the world, though, and how we define the “height” of civilisation, is an idea much more complicated. Even science cannot exist in a vacuum, and the stories often told about who we are as a species and how we came to be are not immune to the sociopolitical pressures of our modern world.

That does not mean we do not know what we know. What it does mean though is that there is robust and informed commentary to be read outside the Western bubble as well as within it. In short, the mathematics of addition and not division should be used to govern the narrative we accept about the origin of our species. It is, after all, a global story, for which we need a broad coalition of global storytellers.

In our interview series, It Began In Africa, we invite you to sit in conversation with a few of these scientists—they'll tell you a bit about who you are, and more, who we are.

Dr Sheela Athreya is a biological anthropologist and associate professor at Texas A&M University-Qatar. Her work centres on the study of human evolution in Eastern and Southern Eurasia through DNA and fossil records, with a wider focus on decolonising the human origin narrative. Dr Athreya is an advocate for the narrative to move away from eurocentrism—she believes that decolonising is not just about amplifying an alternative point of view, but it is also about not centring it in the colonial point of view in the first place. In our conversation, we scratch at the surface of the popularised theories and uncover some of the colonialism and European bias driving them.

I wanted to talk first about the quote from your study that reads “the marginalised non-Western lands and their peoples leaving the order of superior and inferior more or less unchanged through the history of the discipline.” I found that fascinating and wanted to have you expand on that a little bit.

That came about from my co-author, Becky Ackermann. She’s been working in South Africa for the last 20 some odd years, and I gave a talk about how the Asian fossil record has been represented, and she was frustrated because she pointed out that no matter how the narrative goes, Africa is always at the bottom. If it’s the site of human origins, they’re primitive. If it was the last place to become human, they’re primitive. So they can’t win. So it came about from her frustration and observation that the starting point was the primitiveness of Africans and the elevation of Europeans. The irony is that the youngest fossil record for our species and some of the latest developments were in Europe, and somehow, that’s still the pinnacle of our achievement. Everything is now framed as “these various [other] places had art, but it all came together in Europe,” whereas before, in the 1940s and ‘50s, it was “it all started in Europe and no one else became civilised until after we developed art.”

Your study seems to talk quite a bit about the subjective judgment of early human’s civility and how it was used as a weapon to “other” certain sects of the population. Can you expand on that idea and if it has changed at all today?

I think we’re definitely still recycling or reproducing that, just in different ways. Two examples off the top of my head: there’s this field called human evolutionary ecology; it is a field that kind of bridges cultural anthropology and biological anthropology. I don’t want to paint it with too broad of a brush, but it’s problematic in that it looks at non-industrial societies, and oftentimes tries to draw these really Darwinian inferences about human behaviour. First of all, non-industrial societies have been reconstituting themselves over the last 40,000 years just like ours have; it’s not as if they’re stuck in the past. They’re very much a present-day manifestation of how humans interact with their environment, and they’ve been problem-solving over the past 40,000 years too. The second way in which they reproduce that is by arguing that observing the behaviours of non-industrial societies gets us closer to aspects of Darwinian selection. We’re all equally using culture to buffer selection, and so to imply that somehow we can access selection more by studying them is implying that they’re somehow more animal-like.

I’ve avoided that literature so completely, but there are probably people who do it well, and I just don’t know about them. People I respect do think that some of that literature is good. But I think that it’s premised on a very problematic idea.

Another area where I think it’s reproduced is within archaeology. The unbelievably myopic view by some archaeologists that human culture should follow this linear projection towards technological complexities is so embedded in how they frame their findings, and some archaeologists have no problem making the very simple one-to-one correspondence—that if you see a certain type of stone tool, you have a more primitive hominin. The number of sites that have actually yielded Neanderthal fossils is far fewer than the number of sites that have yielded stone tools that archaeologists assume were made by Neanderthals because they’re less sophisticated. So the marker of being a human the way we’re human is to be more technologically advanced, and if we apply that same mentality to living humans, then we’re ignoring the way that culture mediates how you adapt to your environment—you could use a fork or you could use your hands, but you still eat.

Biological anthropologists, for the most part, don’t do that. If you don’t have a fossil clutching a stone tool in its cold dead hand, you don’t assume you know who made it. The division I’m referring to is: if you see upper-palaeolithic tools that are called blade tools, then it’s a modern human site; if you see a flake tool, then it’s a Neanderthal site. That paradigm is still really influential where I work in India.

The version of the paradigm that I’ve had to work is: there is a type of tool called a microlith which is a really small stone blade and several are hafted into a piece of wood or a bone. Microlithic tools were first found in the Near East and were associated with agriculture, so that came to be considered the end of the Stone Age since microlithic technology was considered technologically more advanced. Then microlithic tools were found in South Africa and they dated 70,000 years ago, so it’s like one bizarre exception. But then, over the last 10 years, microlithic tools have been found in India in very solidly stratified deposits around 40 to 50,000 years ago. What is being said is “this is a marker of modern human; we have to ask when did they come here and why did they bring this” instead of “microlithic technology clearly does not need to be built upon blade technology which is what came before it.”

We thought it was part of this cumulative knowledge development process, but it’s clearly not. Therefore, how is this technology mediating adaptation to different environments at different times in human history? That’s what we should be asking, but instead, the dominant narrative—in terms of what I have to frame my grants or publications within—is what does this say about modern humans in India? I don’t think that’s the question. Again the narrative is, “well, microliths are advanced, therefore microlith makers are more civilised, therefore they’re more modern and more human, so we’re going to use that as a marker for moderns.”

Do you think it’s fair to say that you feel that there is an overly linear structure being imposed on this story? Or is it more that you feel we should scrap the whole thing and start anew, coming from different angles? I guess I’m trying to get to: what is the “cardinal sin” in terms of the way this narrative has been structured?

At its heart, the problem with the way this narrative has been structured is that it’s a Judeo-Christian narrative structure. On some level, I’m embarrassed to be painting my points with these broad brushes, but at the same time, there are absolutely patterns and commonalities that are valid and that people who are Indigenous and who do study their own knowledge systems would argue. Also, just to qualify my bonafides a bit, I think the reason that none of this ever made sense to me is because I’m Indian American. I was born and raised in the US, but my dad is a real Hindu scholar, so I learned a lot about Hindu philosophy growing up that I just internalised. Hindu philosophy is very much an Indigenous knowledge structure; it shares way more with that than with Western science—that’s why I think it speaks to me.

Where I’m going with all of this is that the cardinal sin is that Western science aims to find universalities and generalisations, versus Indigenous knowledge where the norm is to take a local approach. Trying to create one narrative for all of humans, for the whole world—maybe it’s not a cardinal sin so much—unless people insist on doing it knowing that they’re doing it, then it’ll be a sin—but right now it’s just a lack of scholars who have that framework being part of the process. That’s one of the problems—Western scholars are speaking to each other in such an echo chamber that no one is reflecting back to them how monolithic and myopic the views are. It’s really inappropriate to try to come up with a universal model that explains the entire human fossil record across a range of ecological systems.

The second thing that I think is a product of the Western Judeo-Christian mind is the idea that you have this one pure form, that it has a creation and that it goes out and spreads its goodness throughout the world. If you read cross-culturally different origin myths, that’s just not common; it’s actually really weird.

The way that the scientists have engaged in this has been equally very embedded in their own local biases, which makes sense—to create this binary between “out of Africa” versus “regional continuity” and “archaic” versus “modern”. Not every society organises itself around these oppositional binaries.

So, obviously there’s a need to diversify the field.

Hell yeah.

What does that look like in a more concrete sense?

There are a couple of ways that we do this better—we do the science better. Some of them you can decolonise without even bringing in other voices. One of them is to obsess way less on species names and labels and way more on evolutionary histories.

The work that I’m doing in India is at this site where we have this rare co-occurrence of fossils and stone tools and art—actually, oddly enough, there’s painted rock shelters. We are not even asking the question “when did modern humans arrive in India and are these modern?” We’re not engaging in the naming question; that’s just really Linnean. Instead, we’re asking about evolutionary history: how did biology and culture vary in the past? What features of biology and culture and genomes co-occurred in India 40,000 years ago? How did that change from 40,000 to whatever the next youngest level of the site is? Technically our job is to be reconstructing our evolutionary history, and that doesn’t start with naming and that doesn’t start with looking for types—those are really Linnean; and Linneaus didn’t believe in evolution!

Because you are saying it’s really important to stray away from this Linnean idea, how can that then be modelled into still teaching that evolution is how we came to be, even though it’s not the evolution that’s in our textbooks?

Those don’t necessarily seem oppositional [sic] to me. It’s more about: if evolution is change over time, then what is the history of how we changed over time? Making it more regional. Good biology is done locally. I don’t come up with a theory for the evolution of all salamanders all over the world, and similarly, it’s not appropriate to do that for humans. That’s a weird biblical thing. If we embrace some of the benefits of non-Western knowledge systems and make it about looking at histories and looking locally as opposed to naming things and trying to do them globally, I think we get better answers that are still testable and repeatable. It’s still science.

I want to talk about the out of Africa model. When I started this story, there was no doubt it seemed in the literature I was encountering that this is the theory; this is what’s accepted; this is what we know. I’m curious about this quote that “its success has as much to do with the sociopolitical dimensions of palaeoanthropology as the actual data.”

Historically, the initial understanding of human evolution was that different regions had different histories. The model that became the multiregional model had its own sort of dark associations, so there was sort of a vacuum to fill. The first person to look at the fossil record broadly was Franz Weidenreich, and he saw a lot of continuity within regions, so the name ‘regional continuity’ was the original concept. This is basic evolutionary biology—there is continuity within regions, and there is gene flow between regions. It was just this very boilerplate concept of a geographically dispersed species.

And then in the 1960s, it was bastardised by this guy named Carlton Coon.

He took it to mean that different people crossed the threshold into Homo sapiens in different regions at different times, and that was actually directly correspondent to how civilised they were as a society. It was revealed later that Coon was a horrible racist. The entire field was trying to grapple with being relevant in the Civil Rights Movement, and so there was sort of a vacuum to fill. Because he took Weidenreich’s model and eliminated the concept of gene flow and added this idea of ‘threshold of humanities,’ it was kind of taboo for a while to work with that.

Then in the late 1980s, when the mitochondrial DNA study came out it coincided with this really interesting time where a Chinese and Australian scholar Wu Xinzhi and Alan Thorne published a paper that said, “Here’s what I’m finding in Australia; are you finding this in China? Yes, okay, cool.”

Then Milford Wolpoff came in and worked with them to bring their ideas into the mainstream. It was really just this idea that made sense from the view of every evolutionary biologist; that when you have a really broadly dispersed gene pool, evolution at the edges is going to look different than evolution in the centres. The mitochondrial DNA study came out at the exact same time, and in addition to all of the debates that were happening with how we’re interpreting the fossils, some of it became this racial debate. Like “you're racist because you’re picking up on Coon’s model” and “no, you’re racist because you’re saying only Africans were human first, and everyone else is sub-human.”

They really were trying to win this debate in a racial context. I personally think that one of the things that made the out of Africa model more successful was that it is much more consistent with this Cartesian view of science that the West has—that everything can be understood by its smallest irreducible part. That’s very Cartesian science, and the multiregional model is very Indigenous science; it’s very holistic, and it’s also voice: it’s the voice of two scholars from two very marginal regions in terms of palaeoanthropology—the Chinese and Australian.

Part of it is because genes are just cool, and we think that genes are identity because it doesn’t occur to us how crazy that is. Trying to use genes and putting genes in this really complex, holistic, cultural model of identity is just way too much work. It’s so much easier to just be like, “I have the M1 C-to-G transition, I’m Native American.” It’s so much easier to just do that than to think how complexly does a Dakota identify as a Dakota because they sure as shit don’t care whether or not they have a C-to-G transition at the seventh locus of their mitochondrial genome.

It came along with this division in American anthropology, of science versus non-science. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a ton of anthropology departments split, and the biological anthropologists went into anatomy and biology, and the cultural anthropologists went into their own social spheres. Genetics just speaks to how—you see this with 23andMe—it’s just really familiar and comfortable to think of ourselves in that way. Most human societies don’t constitute identity that way. I think it’s a real cultural bias, and like I said, very Cartesian. That’s certainly not a global way to conduct science; it’s a very culturally specific way.

We don’t really realise how much our knowledge is mediated, especially science, because we think it’s objective. The only reason I ever critique this is because it’s always bothered me that Homo erectus as an evolutionary dead-end is part of the narrative. That never made sense to me. If I said it didn’t make sense to me, though, it was like “well, Asians are so biased.” I have been told that to my face by so many people. So the lack of reflection of everyone being biased and the Eurocentric bias is part of why we just keep perpetuating these things. I think that’s why out of Africa became the dominant narrative.

My training at Washington University—I was with, I think, just like the most genius people in the world. It [the out of Africa model] wasn’t actually the thing where I was trained; no one took it for granted. It was really heavily critiqued from the point of view of good genetics; it was considered bad genetics based on bad population inferences. There’s a lot of literature out there by really prominent people that critiques this. There’s a certain confirmation bias. Alan Templeton, for example, is a globally renowned population geneticist, and his papers are all over the place talking about how problematic the inferences are and how there’s no data whatsoever to support a uniquely out of Africa model—and he’s not some fringe dude. Even within anthropological genetics, there are people who have been doing population genetics way longer than they’ve been doing human origins; they are the one who are like, “oh, you can’t say that”—like Jonathan Marks. I was trained by these guys, so I learned solid population genetics theory first and then interpretation second. One of the things that’s so apparent is that the results of finding roots in Africa for all of your trees is absolutely a product of population size and not just a single unique origin. It’s not even like I’m saying that; it was published right away in science.

Since we’re tossing out of Africa, what is the framework with which we should look at this story of who we are as a species and how we came to be? Is there a different name that you would give to understand the science or is it just a piece of advice—something like “make your mindset more flexible”?

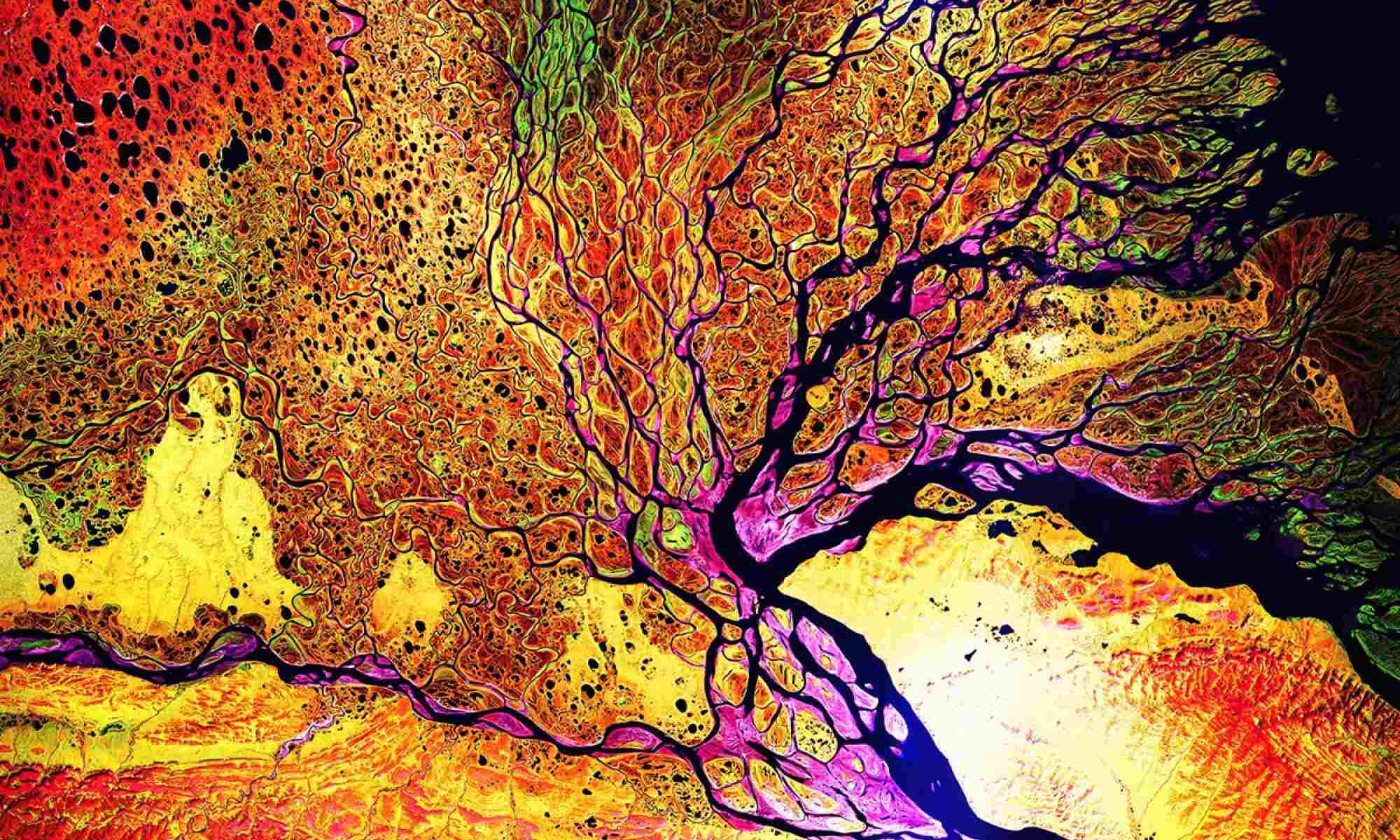

The braided stream model has a lot of appeal to me. It was first described, maybe not exactly in those terms, by a colleague of mine in China, Wu Xinzhi, and he’s around 86 now, so he described it 20 or 30 years ago. My friend Becky, my co-author, independently, without knowing he had published that, also came up with that concept. I think they conceive of it a little differently but the foundational idea is the same—that in the past when you had lower population densities, populations would branch off for a while in terms of evolutionary trajectories, then they would come back together. Some of the streams would rejoin, some of the branches would just kind of dry out. That’s why I like that concept.