“I didn’t choose to be a storyteller; it chose me.”

This is the response I receive from Indigenous Canadian storyteller Kung Jaadee upon asking her why she became a storyteller—and it makes sense. Watching her perform, she is entirely in her element. Her power, grace and authenticity resonate from head to toe, even through a computer screen. Yet, she assures me that before she started telling stories, she was like a little mouse—too shy and too reserved. A woman who had been taught from childhood to be ashamed of who she was. For Kung Jaadee, telling stories was a path towards not only accepting herself but being able to love herself.

”Love is the most powerful force in our universe. I teach little kids this, and I teach really old people this because our world needs more of it every day,” she says.

Kung Jaadee, whose birth name is Roberta Kennedy, is a professional storyteller, educator and published author belonging to the X̱aayda (Haida), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) First Nations. Following Haida tradition, she was gifted the name Kung Jaadee, which means Moon Woman, by her cousin at her great uncle’s memorial feast.

“My ancestors used to believe someone didn’t become a human being until they had their name, their traditional name,” she explains.

For Kung Jaadee, becoming a storyteller was not a choice but it wasn’t an accident either. Her uncle tricked her into it. Under the impression of being invited to sing with him at a performance, Kung Jaadee found herself alone on the stage after her uncle announced he had to go and change his regalia. She laughs as she remembers the moment. A laugh that resonates throughout her body. Her fondness for her uncle and the impact he had on her storytelling is evident.

While her uncle’s trick was certainly a starting point, it was not until she was telling stories at her son’s kindergarten class that she realised just how important storytelling was. For the session, Kung Jaadee brought in her button robe, handmade by her 86-year-old great-grandmother, and told the story of its creation.

“When I was finished telling the story, all of my son's peers looked at my son, and they switched the learning,” Kung Jaadee says. What she is referencing is the negative Indigenous rhetoric which ripples through countries with legacies of colonisation. From a young age, children within such nations are fed shallow and skewed understandings of Indigenous peoples and their cultures, which are often carried with them into adulthood. It was while telling this story that Kung Jaadee realised she could change the narrative. They turned to her son, she remembers, and "they said 'you are so lucky,’ and my little boy sat up so tall, and he was beaming from ear to ear, and I was sitting there, and as clear as day, I remember thinking, ‘That's why I have to do this, I have to do this for him.’”

Kung Jaadee finds strength and healing through storytelling. She shares personal stories, like the story of her button robe and what it was like growing up Indigenous. One of the stories she tells recalls her experiences of discrimination from a young age. She vividly describes a time she was surrounded by 17 children who spouted a seemingly endless number of negative Indigenous stereotypes, until she eventually thought to herself, “there’s so many, it must be true." The bullying she experienced at school silenced her to the point that she stopped speaking altogether. It was only when she performed her story in front of her son’s class years later that she realised she could no longer be ashamed for who she was; otherwise, her children would grow up to be ashamed of who they were.

The shame that Kung Jaadee talks of is a result of colonisation—the oppression and years of abuse that Canada's Indigenous population have had to endure. It's a shame that has been passed down through the generations and has become a vicious cycle—one that Kung Jaadee is dedicated to breaking.

Kung Jaadee's family, like many Indigenous peoples in Canada, were subject to church and state attempts “to kill the Indian in the child.” This was approached through the institution of Indian day schools and Indian residential schools. Day schools allowed Indigenous children to continue to live with their families and remain in their communities throughout their attendance, while residential schools forcibly removed children from their families for extended periods of time. Many grew up never knowing their families. Kung Jaadee's mother and siblings were forced to attend the day schools and her paternal grandfather was taken to a residential school.

“My cousin’s mother was taken to residential school when she was 6 years old, and she was returned home when she was 16 years old,” she explains. “She didn’t get to go home in 10 years. Not a single summer. She returned to her parents as a stranger, her parents strangers to her.”

The sole purpose of both day schools and residential schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into the dominant Euro-Canadian culture. Attendance at these schools was mandatory for all Indigenous children from the age of four upwards. Children were permitted to speak only English, were stripped of their clothing, made to cut their hair to mimic Euro-American styles and were forced to change their Indigenous names to European names. Any parents who tried to keep their children at home were arrested. Many of the children who attended residential schools died due to horrific living conditions or while trying to escape. Due to inconsistent record-keeping, it is still unknown exactly how many children died, but it is thought to be anywhere between 3,200 and 6,000. Many of these children were buried without their parents' knowledge. In all, over 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend these schools.

Within both day schools and residential schools, many children suffered from physical, mental, verbal, emotional, spiritual and sexual abuse. On release from the schools, children were expected to return to their communities and institute change from within. Many children struggled on returning as they were unable to recognise the cultures they had been taken from. For those who did not return, they faced alienation when they were not accepted by the Euro-Canadian culture they had been forced to adopt. The last residential school closed in Saskatchewan in 1996. To this day, the fight to recognise the survivors of these schools continues.

“The end result of the Indigenous children attending the schools is a lot of post-traumatic stress, alcoholism and suicide,” Kung Jaadee explains. “Suicide continues to rise amongst young people in our communities across the country. I’ve had nine cousins commit suicide since I was 13.”

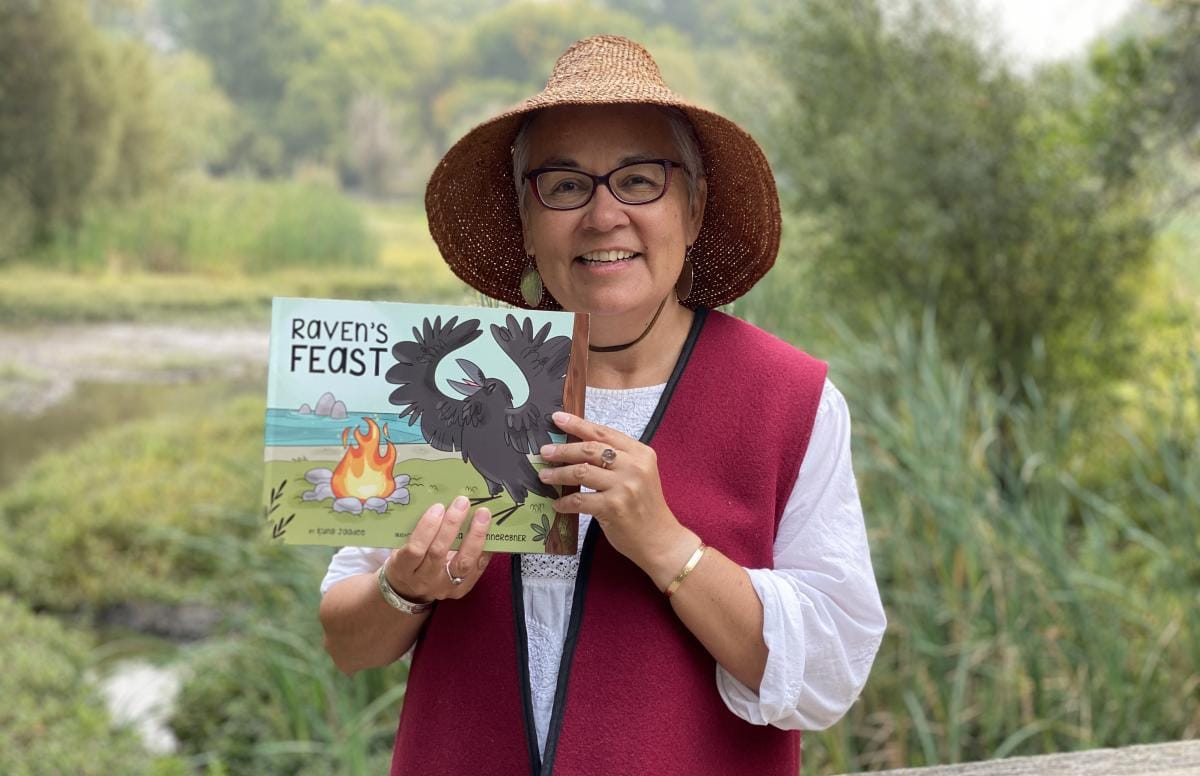

Alongside personal stories, Kung Jaadee uses her storytelling to reinvigorate her people’s traditional legends. These stories teach listeners morals like loving and caring for one another and sharing what you have. Having authored four children's books, she is known best for her stories which centre around Raven, a heroic mythological creature that appears in traditional Indigenous creation stories.

“Raven is our trickster and creator, both. He often tries to trick others, and because of that, he is tricked himself. He loves food and will eat all the fish, or all of the berries. He’ll blame someone else though. He created the world from flying in the darkness for aeons of ages. The flapping of his wings helped to create our world," Kung Jaadee tells.

These stories were not easy for her to find. The impact of colonisation on her people and the disconnect that it caused between generations has meant she has had to go on a journey to find the stories themselves. In a way, her journey to gather them has become a story in and of itself.

“I didn't know that we actually had stories in our elders. You know, if I had known that, I would have gone to see those elders and recorded them telling the stories just to keep them alive,” she explains.

Her grandfather was known to be a great storyteller; however, the lasting impact of a lifetime of abuse meant he, like many others, closed himself off as a way of coping. Instead, Kung Jaadee found herself beginning with the research of a European man called James Deans. It was not long until she realised he knew a lot less than he claimed, even incorrectly referring to her people as the Haidari. As she progressed further into her research, she found many of the stories out there to be incomplete, or in the case of Deans, simply wrong. This was where her uncle came in; he may have tricked her into telling stories, but he made sure to teach her how to find them.

“My favourite story is ‘The Berrypicker in the Moon’,” she says. “It was a story I researched and only found part of it. So I asked my uncle about it, and he smiled a cheeky smile at me, and he asked me, ‘What does your heart tell you about how it ends?’ I had to trust the ending would come to me and it did.”

Kung Jaadee has an innate trust in the spirit of her ancestors and their guidance, and so far, they have delivered. They have provided her with light through the tunnels of integenerational trauma, and helped her realise what she is here to do.

“My work is to try to make this world a better place," she says. "I want others to do the same. I really believe that every single nation, and I’m thinking there are four main nations on our planet, we all hold the secrets to life in our world. And we’re meant to actually figure out what those secrets are, come together and share them with one another so that we can make a better world.”

Every culture, no matter where, is built on a foundation of stories. It is through them that we learn who we are, what we stand for and why we are here. For Indigenous peoples within colonised countries, storytelling has become an act of defiance. For years, they have been silenced, their cultures exploited and their voices overwritten. They have had to fight to keep their stories alive. Now, Indigenous storytellers like Kung Jaadee are changing the narrative.

If you wish to find out more about Kung Jaadee, she encourages you to reach out to her through her website and her agent’s website, where you will be able to learn more about the work she does.