It is innately human to wonder about oneself—likely a side-effect of our big brains and our even bigger egos. How much do we need to wonder though? Not as much as you might think. The human origin story is studied exhaustively by palaeoanthropologists and archaeologists. They could tell you about the structure of your spine and they could tell you why you want so desperately to be part of the in-crowd (hint: it has something to do with limited resources and high levels of cooperation). The catch is, they might tell you different things.

It is an indisputable fact that modern humans—Homo-sapiens—came to be through the process of evolution. The fossils make that clear. How we spread across the world, though, and how we define the “height” of civilisation, is an idea much more complicated. Even science cannot exist in a vacuum, and the stories often told about who we are as a species and how we came to be are not immune to the sociopolitical pressures of our modern world.

That does not mean we do not know what we know. What it does mean though is that there is robust and informed commentary to be read outside the Western bubble as well as within it. In short, the mathematics of addition and not division should be used to govern the narrative we accept about the origin of our species. It is, after all, a global story, for which we need a broad coalition of global storytellers.

In our interview series, It Began In Africa, we invite you to sit in conversation with a few of these scientists—they'll tell you a bit about who you are, and more, who we are.

Dr Chris Stringer is a professor and research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London and a fellow of The Royal Society. Stringer's work as a palaeoanthropologist has led him to promote the recent African origin model of human evolution. In our conversation, we explore the fossil record itself and the story he thinks it tells about the birth of our species and its incredible staying power on Earth.

I know you're a proponent of the out of Africa theory which in recent years has shifted to the multiregional African origin theory. Can you explain that shift? What important new evidence has been found?

The multiregional in Africa model is a term I have used, but I think some of my colleagues who agree with the model don't think it's a good name for it. If we go back to the 1980s and 1990s, there were these two polarised models: pure out of Africa—that modern humans only originated in Africa and we evolved there. Then we came out and replaced all the other humans around the world like the Neanderthals. At the other extreme, there was the multiregional model identified with people like Milford Wolpoff that said actually there was this earlier form of human that most of us call Homo erectus, and this earlier species was around in Africa, Europe, Asia and Indonesia, and it was there 1.5 million years ago in each of these places. Then in each area, it evolved towards modern humans. So modern humans didn't evolve in any one place, they evolved all over; everywhere where ancient humans lived, they evolved toward modern humans. They didn't speciate, they didn't go in different directions because they were interbreeding with each other across that whole range, so basically it's the evolution of one species for 1.5 million years. That's the classic multiregional model.

In the last, let's say 20 years, the genetic data built up to show that if we look at our genome, most of it undoubtedly comes from a recent African origin. But, what we've also learned is that it's not 100 percent; there was interbreeding outside of Africa. When the ancestors of Homo sapiens came out of Africa, maybe 60,000 years ago, they encountered Neanderthals, and they encountered Denisovans. They did a bit of interbreeding with them, which means that today most of us in the world have around 2 percent DNA from Neanderthals, for example, so it's not 100 percent recent African origin. It's more than 90 percent but with a bit of Neanderthal DNA added in, and over in the Far East and Southeast Asia, a bit of Denisovan DNA added in as well.

Once we agree that modern humans have their main origin in Africa, the question is how did that happen in Africa? Some people have favoured the origin of modern humans just in one region and then spreading out from there. East Africa is maybe the favoured area for a number of people. There's also another group that thinks that South Africa was actually leading in the evolution of Homo sapiens and then, having evolved there, Homo sapiens spread across the African continent and then out of the African continent.

Recently, as we've got a better fossil record and better dating for some of the fossils, what we can see is that there isn't—at least in my view and the view of a number of us now—there isn't evidence for a single place of origin. What we find is that modern human features are appearing in different places around the same time. Ethiopia, Morocco, South Africa—each of them has fossils that show some modern human features. If we look at the time between let's say 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, it looks like modern humans are evolving bit by bit in different parts of the African continent and they're interchanging genes with each other. This is what's become known as African multiregionalism.

Because of the previous usage of multiregional—that global model that's been pretty well disproved—a lot of my colleagues who argue for multiregional African origin prefer to call it a pan-African origin.

So let's talk about the pan-Africa model. Africa, we know, is a huge place, complex climates—for example, at times the Sahara Desert is [as] huge as it is now, and the populations in North Africa were isolated from populations in East Africa and Southern Africa. You've got this big empty space; no humans could cross it. These populations were pinned back in their own little areas, and if things got very bad, some of them probably died out. But at times, the Sahara Desert [would] become well-watered, and when that happened, we know from archaeology, from stone tools, that people actually spread along those lakes and river courses and across the Sahara. That meant these populations could come in contact with each other; they could exchange genes through interbreeding; they could exchange cultural ideas.

In Southern Africa, it's a similar story. So we end up with a complex picture of populations, at times, evolving on their own in their own direction, and at other times, exchanging genes and cultural ideas. There's no single origin for modern humans—we evolve[d] in various parts of Africa, kind of in parallel with gene flow.

Do you think there can be a true definition of species given that it's not one group that we're following in a linear evolution?

It's a tricky one because obviously there are many different species concepts. The biological species concept says that species don't interbreed with each other, they're reproductively isolated, but we know from many DNA studies that that model doesn't work for many closely related bird and mammal species. Interbreeding between closely related species is actually quite common in nature, and it certainly happened with us.

So, I don't apply the biological species concept if I'm talking about humans. Even though we interbred with Neanderthals, if we want to decide if we're the same species as Neanderthals, we need to look at the morphology—what's present in the fossils. When we do that, modern humans are clearly a distinct species; we have a set of shared features. We've got a high and rounded skull. We've got small brow-ridges, or maybe no brow-ridges at all. We've got a small face tucked under the braincase. We've got relatively small teeth particularly at the front of the jaw. We've got a chin on the lower jaw, and, in our skeleton, we've got a narrow and tall ribcage compared with the Neanderthals and Homo erectus. We've got a narrow pelvis that's not flared. For me, those separate us from those other humans.

We can look for those features in the fossil record, and if we do that, we can find them in Africa some 200,000 years ago. There's a partial skeleton from Omo Kibish in Ethiopia, and that's about 195,000 years old, and that skeleton, as much as we can determine its features, it’s a modern human. The problem is, as you go further back, some of those features may not have evolved yet. This is the issue: how to recognise Homo sapiens as we go back in the fossil record.

In my view, if there are enough features to show it's on our line of evolution after the split from Neanderthals, I will call it Homo sapiens, but it won't have all the features of modern humans because obviously evolution happened along that line. I take an evolutionary species concept that basically, it's a lineage, based on the split with the closest relatives, which in this case are the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

Can you talk a little bit about why Homo sapiens reigned triumphant over the Denisovans and Neanderthals? Is it those evolutionary qualities that made them more likely to survive?

This is one of the big questions. When we look at big the picture, 100,000 years ago, there were at least five kinds of humans around the earth. We'd been evolving in Africa, the Neanderthals had been evolving in Europe and Asia, the Denisovans had been evolving over in the Far East, on the island of Flores you've got Homo floresiensis, on the Philippines you've got Homo luzonensis, another dwarf species. Maybe Homo erectus was still surviving in Java, we don't know that for sure. It was a pretty complex story 100,000 years ago, and yet today there's only once species and that's us. All those others have gone, at least physically—a bit of Neanderthal lives on in us in the DNA, a bit of Denisovan lives on in many people in the Far East and South East Asia in the DNA.

But physically they've gone and why is that? We really don't know. There are many different ideas about it. It was probably a combination of factors. For the Neanderthals, the genetic data shows that they were quite low in diversity and probably quite low in numbers. I think they might have suffered attrition from regular repeated climate change. From about 100,000 years onwards, we know that the Atlantic Ocean changed regularly and rapidly from being nearly as warm as it is today to being bitterly cold, so Europe was suffering these regular climate insults. The Neanderthals and everything in Europe—the animals, the plants—they were suffering the climatic stress of these regular changes, and I think the Neanderthals never had a stable playing field to really build their numbers up. I think Neanderthal diversity was whittled down, and by the time modern humans encountered them 60,000 years ago, I think they were probably already a threatened species, and it may not have taken much to push them over the edge to extinction. Modern humans, just by entering Neanderthal's territories, wanting to eat the same food, wanting to collect the same plant resources, wanting to live in the best sites, the best valleys and so on, there would have been an economic competition. There's been a recent suggestion that there was basically long-term warfare between us and the Neanderthals. I don't believe that. I think that the Neanderthals would have moved away if there was a dangerous situation; they're not going to fight, especially if they're low in numbers and low in population density. What they would do is move to another location. The Neanderthals and modern humans were in an economic competition where they shared resources, and modern humans were maybe just a little bit better at exploiting those resources.

Something that comes into play is this idea of energy efficiency. So recent research suggests that Neanderthal lungs were probably 20 percent bigger than our lungs—they were very high energy, they were high in their demands, they needed more energy than we did to basically just conduct their everyday lives. Modern humans are a more economical model of human—our hipbones are narrower, our lungs are smaller, we can get by on less energy resources. That means on any given land with plants and animals, you can have more modern humans than you can Neanderthals, given the same resources. So perhaps, it was a matter of energy efficiency. Our technology, perhaps, was also a little more efficient in gathering plants and animals. It's not a simple matter—it's partly anatomy and physiology, social system differences. Maybe we had bigger networks of people, we shared information, and that also gave us an advantage. We had specialised tools to a greater extent than the Neanderthals did. All of those things add up to give us the edge, but that edge is only a product of the last 60,000 years or so. Modern humans had probably encountered Neanderthals a number of times before that in the Middle East and even in eastern Europe. In the earlier times, modern humans did not have this advantage, and we don't really know—you can't put your finger on a single thing that makes us the species that will replace the Neanderthals.

The same thing happened with the Denisovans in the Far East, and their DNA suggests that they were more diverse, they were probably large in numbers and they were spread over a lot of Asia and Southeast Asia. They too got replaced. So whatever it was, it also worked over in the Far East in a different environment against a different species. We're still looking for the answers to that.

Another suggestion is survival of the friendliest—that modern humans in a sense have self-domesticated. We are friendlier to each other. Okay, we've got nasty weapons if we need them, but in general, modern humans communicate and work together toward common goals. Within a particular group, we cooperate very well; we have ways of solving problems socially, and that means the group can function very well. The suggestion is that we were able to make wider networks of more people, and that's obviously an evolutionary advantage. When times get bad, if you can rely on your neighbours for help, that can help you survive; if your neighbours are hostile, that's bad news.

Do you think we as a society need to make our views more flexible in understanding who we are and where we've been?

The Neanderthals were certainly intelligent. They survived in difficult conditions, and they certainly had complex technology. They seem to have buried their dead. They were fully human in many ways. I think that our level of language complexity was maybe up a level from theirs, so we have greater complexity of thinking. Neanderthals were using pigment to mark their bodies and mark jewellery, maybe the walls on caves. But, up to now in my view, there's no definite evidence of representational art by a Neanderthal. Once we get to modern humans even 40,000 years ago in Europe, we find statuettes of animals and humans, so humans are creating representational figurative art. There's no evidence that Neanderthals did that. There could be some separation there as sort of self-recognition, the fact that we can make images of ourselves. Maybe that tells us something about modern humans.

Let's say we're inducting fossils into the evolutionary hall of fame. Are there three to five that you think are the most important for the layman to understand?

Okay, iconic fossils. Well probably in terms of history, the Lucy skeleton was important. That was the first skeleton of an Australopithecus that was complete enough to show that these creatures, even three million years ago, were walking upright.

There's a skeleton in Kenya—from Nariokotome, in northern Kenya. Turkana boy, he's often known as. This skeleton is about 1.5 million years old and it's still the most complete Homo erectus skeleton that we've got.

Later on in the story, there are a number of Neanderthals. The site of Sima del Huesos in Spain near Burgos—there's a cave chamber, and it doesn't just have one skeleton, it has 29 partial skeletons, can you believe? These are about 430,000 years old. There are thousands of bones from the skeletons; the bones are jumbled up but you can assemble them into individual skeletons.

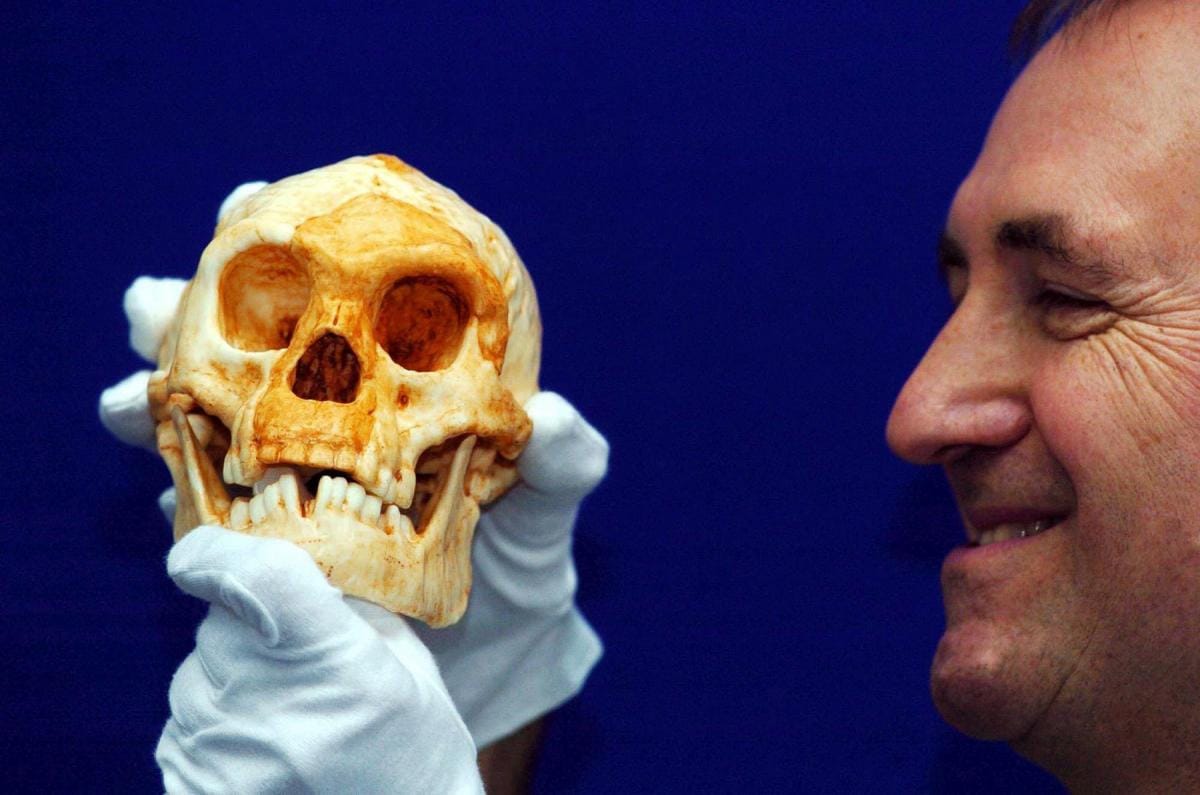

The Homo floresiensis skeleton is another one.

The Neanderthal skeleton from La Ferrassie in France is a beautiful skeleton; it's one of [the] best-preserved Neanderthals that gives us a really good picture of Neanderthal anatomy.

In terms of African origins, it's probably a toss-up between the Jebel Irhoud material I mentioned from Morocco at 300,000 [years], and also that Omo Kibish skeleton which is not very complete but is important because it shows us that there were modern humans in Ethiopia around 200,000 years ago.

I suppose the Dmanisi finds from Georgia—they're about 1.8 million years old, and you've got partial skulls from there of a very primitive Homo erectus.

All of those I would say are all really important fossils.