To step foot in a national park is to witness pristine ecological beauty: the lush forests, vast landscapes and diverse wildlife populations have proved popular amongst American people since the parks’ inceptions.

These tourist attractions have drawn the attention of 327.5 million people in the year 2019 alone and span across “more than 400 areas covering more than 84 million acres in 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Saipan, and the Virgin Islands,” according to the National Park Service.

These lands, first established by the signing of the Yellowstone Act in 1872 and more popularised through the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, were anointed by the government as a “gift” to the American people. Born from the cultural shift during the urbanisation period of the 19th-century, these parks stood as the pinnacle of “good all-American” nationalism, further spreading the idea of ‘Manifest Destiny’—the divine right for Americans to settle all lands—throughout society. Yet this destiny, like many others from the archives of the United States’ past, was more to conquer and destroy than to protect and cherish.

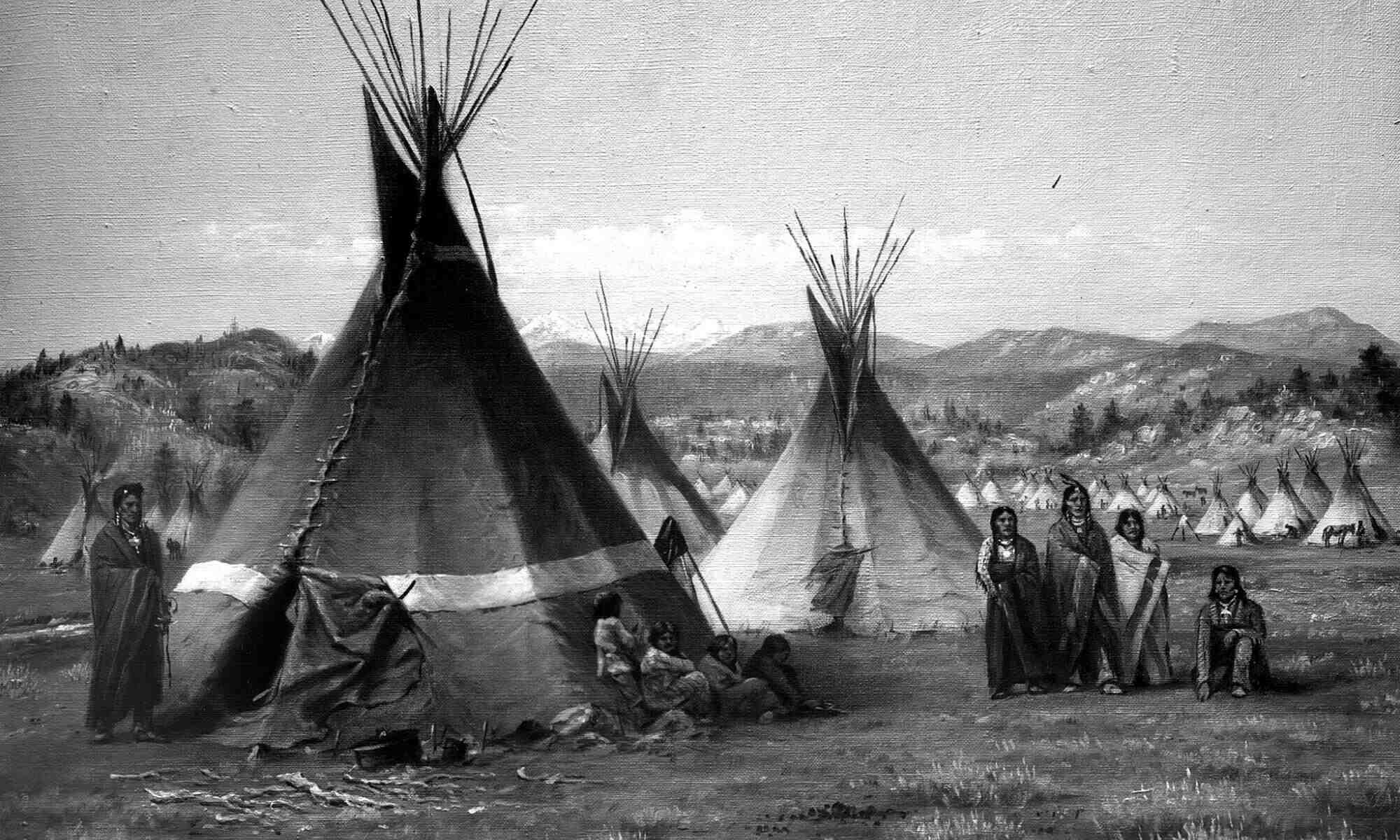

“Conquer who?” you may ask. Unbeknownst to many, the creation of national parks was simply another instance of Native American land being plundered by European-Americans. You see, to step foot in a national park today is really to stand on a battlefield. Or in other terms, a cultural graveyard.

* * *

Journalist and activist Dina Gilio-Whitaker identifies as a “survivor”. As a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes, she knows that “anyone who’s Native in the United States right now is a survivor of a 97 percent genocide. And that’s not overstating it at all.” Journalist and activist Gilio-Whitaker has dedicated her life to supporting Native communities, publishing two novels and winning the Native American Journalists Association Media Award in 2015. Her books As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock and “All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans (co-written alongside Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz), discuss the social and environmental issues that plague the Native community today—one of them being the National Park Service.

“[National parks] were created by a convergence of circumstances,” says Gilio-Whitaker. In the early 19th century, America was dealing with rapid urbanisation, surges in population growth and developing social perspectives regarding land and wilderness—all of which influenced their relationship with Native communities. Historically, these factors “always [come] with aggressive policies towards Native people,” she explains. This instance is no exception.

“National anxiety and angst about modernity and the impacts of urbanisation on the East Coast raised red flags about the overuse of resources, polluting of the natural world and the loss of “wild spaces”. That combined with this parallel narrative of Manifest Destiny meant violently getting rid of Native people from their own homelands. All of this drove the impulse to create a natural park system to protect a “wilderness” which is now a social construction,” says Gilio-Whitaker.

In his incredibly influential novel Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, Mark David Spence supports these sentiments. As an author and advocate for Native communities, Spence is an expert on the relationship between national parks and Native disruption. Spence explains how the social construct of “wilderness” created by European Americans was drastically different from how Native communities viewed land—national parks were “more about the nation and the myth of how the nation came to be” than natural beauty.

Native communities built their lives around their surroundings—ecology and spirituality were seamlessly combined. European Americans, on the other hand, were concerned with other things, in this case more nationalistic appreciation for the American government, and more recently, USD 35 million in economic revenue.

Another key distinction between Native’s views of wilderness and those of European Americans is the separation between people and the land. For European Americans, these serene landscapes were thought to be beautiful for their purity, emphasising their removal from the daily hustle of urban life. As Spence writes, “uninhabited wilderness had to be created before it could be preserved,” giving European Americans what they thought was an excuse to remove anyone from this precious wilderness. However, for the Native communities, this land was more than a vacation spot. “The land is everything to Native people—Native people are the land. That’s how we say it, ‘We are the land’,” says Gilio-Whitaker

So how did European Americans go about taking Native land to build their nationalistic parks? Short answer: treaties. Yet these “agreements” proved to be just as detrimental as physical violence. Because, as Gilio-Whitaker puts it, “Those treaties were imposed at the barrel of a gun.”

Land treaties were one-sided agreements, imposed on the Native American communities whether they liked it or not. Through the use of these documents, European Americans further exploited their access to the land, displacing huge numbers of Natives—exactly 26 Native tribes lived in Yellowstone alone before being forced out in the 1870s.

European Americans committed these acts under the guise of making parks “safer” for visitors. They used this racism to further substantiate the horrendous and untrue stereotype of Native Americans as “dangerous” and “savage”. However, many Natives didn’t leave their sacred lands without a fight. As years passed and more land was converted into national parks, wars broke out, one of the most famous being the Nez Perce War of 1877. This battle, in particular, was initiated when the United States broke the Walla Walla Treaty, an agreement that would allow tribes 7.5 million acres of their ancestral land.

This was not the last time European Americans broke a treaty. In her article for Collectors Weekly, columnist Hunter Oatman-Stanford writes, “Indigenous Americans eventually began referring to such treaties as “bad paper” because they learned the written contracts of European Americans were untrustworthy.” Forcibly removing Natives from their homelands and sending them to reservations not only negatively impacted 19th- and 20th-century communities but modern tribes to this day.

Native Americans have the highest rates of COVID-19, diabetes and suicide deaths of any ethnic group. They make up 2.4 percent of the population. Gilio-Whitaker cites this “historical continuum” of systemic oppression and forced assimilation as the cause. While the wilderness was just a thing to own for European Americans, removing Native communities from their ancestral lands also took away their medicine and native food sources. Years of trauma and degradation have plagued Native American communities for generations, and somehow their struggles still go wildly unnoticed.

So what can we do to help? Gilio-Whitaker urges us to steer clear of performative petitions and work to educate ourselves. After all, the lack of knowledge regarding the Native struggle is incredibly prevalent, one of the worst stereotypes of Natives being that they’re “shadows of their former selves,” according to Gilio-Whitaker.

“If you can de-legitimise a person's existence—that’s part of the dehumanisation that’s happened to us—and you can keep doing that systematically, you can continue to legitimise the violent foundations of our country and perpetuate those lies. And that’s the conversation we’ve yet to have,” she says.

Americans need to be held accountable and face the taboo notion of mass genocide and land theft head on. Everyone who lives on US soil needs to realise that they’re on stolen land, the very ground they stand on is rich with culture, history and bloodshed. To recognise our present, we must wrestle with the past of turmoil and destruction that gave rise to society as it exists today. To quote Gilio-Whitaker, we must reckon with our “settler fragility”.