Amid Auckland’s housing crisis, HomeGround stands as a revolutionary solution that addresses more than just homelessness. Drawing on the expertise of Tiziana Panizza Kassahun, an international urban theorist and human rights advocate, we explore how HomeGround incorporates dignity, cultural relevance and sustainability, setting a new benchmark for inclusive urban spaces that serve both current residents and future generations.

Perched beneath the shadow of the Sky Tower, a contemporary building in earthy hues quietly commands attention. What may initially seem like another modern addition to Auckland’s skyline reveals a far greater purpose. Behind its sleek facade lies a sanctuary of compassion—a place of healing and transformation where architecture transcends aesthetics to embrace humanity’s most vulnerable. Opened by Auckland City Mission in February 2022, HomeGround serves as a lifeline to those experiencing homelessness in Auckland city, which exceeds 18,000 individuals. It integrates permanent housing with comprehensive health and social services, all within one sustainable, culturally rich environment.

As the housing crisis continues to escalate, HomeGround proves that beauty, innovation, social responsibility and sustainability can seamlessly coexist in modern architecture. By prioritising people and embracing innovative design, it sets a new standard for what architecture can achieve in addressing pressing social challenges.

Designed by Stevens Lawson Architects and constructed by Built Environs, HomeGround won the 2022 Auckland and New Zealand Architecture Awards. It reflects Auckland City Mission’s vision of "housing for all," accommodating up to 3,000 clients with 80 studios and one-bedroom apartments, alongside integrated health and community services. Every detail, from the open-plan layouts to the on-site pharmacy and medical centre, embodies the principles of trauma-informed architecture, prioritising safety, security and calmness amidst the bustling city.

According to a case study provided by the architect:

“The combination of accommodation and support services ensures the City Mission team can respond to people in an integrated and holistic way. Facilities include a commercial kitchen and community dining room, public showers and toilets, a public medical centre and pharmacy, addiction withdrawal services, activity spaces (for art, carving, music and drama classes and workshops for the homeless community and residents), a rooftop garden, and a sacred space.”

Drawing on biophilic design principles, the building seamlessly integrates natural elements through organic materials, warm lighting and soft hues, creating a welcoming, residential atmosphere that contrasts with the sterility of typical institutional spaces.

Guided by the principles of manaakitanga (hospitality) and kaitiakitanga (stewardship), the architects worked closely with mana whenua Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei to align the space with Māori whakairo (carving) and tikanga (protocols). A large proportion of the people served by Auckland City Mission are Māori or Pasifika, and the design reflects this connection through the use of structural materials, symbols and artefacts, all of which come together to create a sense of healing and belonging. The gabled roof has a multifaceted meaning, drawing together aspects of both the church and the wharenui (Māori meeting house), symbolising dignity through the fusion of traditions and values.

The case study highlights:

“The project narrative developed by mana whenua Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei is founded on the idea ‘Finding your way back home’. From here, a co-development process led by Graham Tipene produced a set of Te Aranga Design principles specific to the project, supported by City Mission staff and client groups. In response, Māori whakaaro and tikanga are in place throughout the building in a meaningful and tangible way.”

The building not only embodies cultural values but also embraces environmental stewardship. The design reflects a strong commitment to sustainability, using cross-laminated timber, an ecologically advanced waste management system and on-site food production. The result is a space that is more sustainable than typical buildings, with a significantly lower carbon footprint—129 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent per square metre (CO₂e/m²) compared to 638 kilograms CO₂e/m² in similar structures. This measurement represents the total greenhouse gases emitted during the building's life cycle, covering materials, construction and operation.

The importance of human rights in architecture

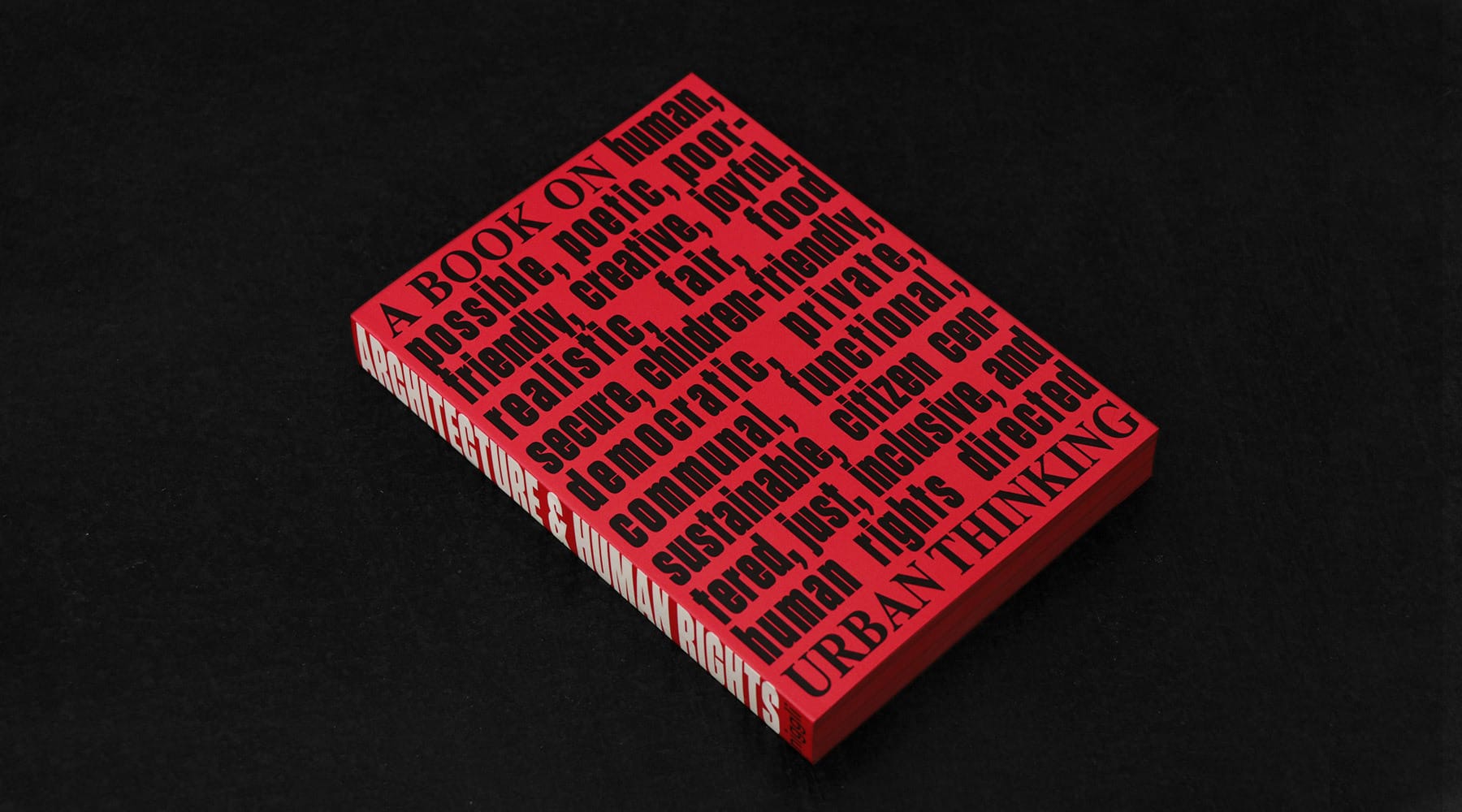

Tiziana Panizza Kassahun, a human rights advocate and the author of ground-breaking book, Architecture & Human Rights, shared insights with The Lovepost about the impact of architecture on individuals and communities. Central to Kassahun’s work is the belief that architects and planners must create spaces that reflect dignity, empathy and cultural respect, transforming cities into more equitable environments. She stresses the importance of open dialogue with the communities who inhabit these spaces, advocating for a design process based on consultation and collaboration. “There is no designing without first identifying the objectives and challenges [of the people],” she says.

Her interest in the relationship between human rights and architecture began during a trip to Ethiopia, where she witnessed homes desecrated as result of ethnic cleansing and political turmoil. After engaging with communities, Kassahun realised that development is not just about providing four walls and a roof—it’s about embracing people and their need for identity and belonging. While structures are often designed for specific functions—a chair to sit on or a book to read—Kassahun challenges us to think beyond these uses, arguing that spaces should enrich lives, promote inclusivity and create emotional connections, identity and cultural relevance.

Building on this understanding, Kassahun extends her philosophy to communal spaces, recognising their potential to fulfil a range of needs beyond their conventional roles. She points to libraries as an example. While we may view places like libraries as merely for borrowing books, or shelters as places for rest, the experiences people have in these spaces go far beyond what we might expect. A library is a place to access information, communicate with loved ones and for communities to come together. Kassahun suggests that when creating these spaces, architects and designers should think about the multitude of purposes one room can provide. “Why not a shower, why not a locker? [In a library,] you are not there just to read, why don’t we think about not just the necessities, but what it means to be human.”

Furthermore, she believes architects have a responsibility to design spaces that serve both present and future generations, ensuring resilience and wellbeing for the long term.

HomeGround exemplifies this philosophy by incorporating the Living Building Challenge and Breaking Ground principles, both of which emphasise holistic, human-centred design. The Living Building Challenge focuses on creating “spaces that are socially just, culturally rich and ecologically restorative,” aiming for regenerative, sustainable design that gives back to the environment. Breaking Ground views home as a support system, using data-driven strategies to help people transition out of homelessness. These principles have been adapted to meet the needs of Aucklanders and City Mission staff, while maintaining the importance of open dialogue. The regenerative design ensures that the building not only preserves ecosystems but also creates a sense of community and belonging, addressing the emotional, social and physical needs of its residents.

An essential aspect of HomeGround’s design is its trauma-informed approach, which aligns with its commitment to creating a safe and supportive environment. Features such as natural light, calming colours, and private, self-contained apartments offer residents peace and autonomy. Communal spaces, like the rooftop garden, are carefully designed to promote connection without overwhelming individuals who may feel vulnerable. Additionally, spaces dedicated to addiction services include safety elements like anti-ligature designs, ensuring that residents are protected and supported as they navigate recovery.

Beyond providing shelter, HomeGround integrates housing, rehabilitation pathways and social services, making it a comprehensive space that enhances the psychological wellbeing of its residents.

Kassahun, while acknowledging the success of HomeGround, highlights the complexity of designing truly inclusive spaces. She maintains that we cannot stick to the blueprint of HomeGround alone. She suggests that we must acknowledge that cultural practices can conflict within a space. “People cannot live inside because they cannot adapt. They have a different concept of family and respecting each other.” By including an array of different cultural perspectives, there is a possibility of a home-like place for all—but it’s not that simple. Different communities often have unique concepts of family dynamics, personal space and social interaction. A design that works for one group might not be suitable for another if these cultural nuances aren't considered. Kassahun stresses that, to create truly inclusive spaces, architects and designers must consult with all cultural groups, not just the predominant ones in New Zealand, ensuring that cultural differences are respected and acknowledged in the design process. Achieving a space where everyone feels at home is a difficult task, especially in a multicultural society like modern Aotearoa.

The law and human rights

While inclusive design can address the immediate needs of diverse communities, the legal framework that underpins housing rights is equally important. Legal frameworks, both inadvertently and intentionally, shape the lives of New Zealanders, and it is essential that the human right to adequate housing in New Zealand is fulfilled. This right is enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, along with other ratified conventions. New Zealand has also committed to implementing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). HomeGround reflects these principles, particularly SDG Goal 11, which focuses on creating inclusive cities with resilient and sustainable urban development, offering access to adequate housing, transport and green spaces.

But questions remain. Why aren’t these principles seen more commonly in everyday life? Whose obligation is it to uphold these rights? Reflecting on how the law can act as a catalyst rather than a mere textual artefact, we are challenged to consider and confront this human dimension.

Kassahun argues that laws, while essential, often remain abstract—they don’t always address the individual realities of the people they are meant to serve. She asks, “How can a law drive and inspire what we do?” Instead of seeing laws as something that only exists on paper, she suggests that we need to actively listen to the lived experiences of people to understand how these laws impact their daily lives.

For example, let’s consider housing. Changing Auckland’s zoning laws to allow for more affordable housing may seem like a step in the right direction. But if we only focus on the technicalities of the law, without consulting the people who will be affected, we risk missing the mark. Yes, it might allow for more housing to be built, but without considering the broader community needs, it could backfire. Elderly residents, for example, may be forced out of their long-term homes due to rising costs and disruptions caused by new developments, which could isolate them from essential services and community networks they've long relied on. Even if they are looking to downsize, new developments might not cater to their needs for smaller, accessible homes, leaving them with no choice but to relocate elsewhere, away from the communities where they’ve lived for years. On the other hand, young professionals might struggle to afford even "affordable" housing. Rising living costs in newly developed areas and lack of access to convenient transportation and job centres could leave them financially stretched. Without addressing these specific needs, these groups could be left out, despite the intention to provide more housing for all.

Many developments also continue to prioritise Western, predominantly White, ways of living, often overlooking the needs and cultural practices of marginalised communities such as Māori and Pasifika. These communities may require different housing designs, such as larger homes for extended families or communal spaces reflecting collective living practices. By not considering these cultural perspectives, new housing developments risk excluding these groups or forcing them out of the neighbourhoods where they have long lived, a pattern often seen in gentrifying areas. This highlights how consultation and design processes must go beyond superficial engagement to genuinely reflect the diverse realities of New Zealanders.

While community consultation is a standard part of drafting housing policies, the process often falls short of fully incorporating the multilayered experiences of diverse groups. Public consultations, town hall meetings and surveys are valuable tools, but they are often too surface-level, with limited follow-up or action on the feedback received. This can result in laws that technically fulfil consultation requirements but fail to truly reflect the challenges of those they are meant to serve.

For consultation to be truly effective, it must go beyond checking a box. It requires sustained, in-depth engagement with communities, particularly those who are marginalised or disproportionately affected by housing issues. This could include continuous dialogue with community representatives, deeper analysis of the specific needs of vulnerable populations and active collaboration in co-creating solutions. Unlike the typical consultation process, this approach would involve ongoing participation throughout the entire policy-making process, ensuring that the voices of those affected remain central at every stage.

Just as architects like those behind HomeGround engage in open dialogue and in-depth consultation with communities to ensure that their designs address specific cultural, social and emotional needs, lawmakers must adopt similar practices.

Looking to the future

HomeGround demonstrates how human potential can flourish through thoughtful architecture and genuine consideration. HomeGround regularly welcomes a substantial number of people, many of whom have endured extreme hardships. It is heartening to see architecture that not only supports those facing such challenges but also accommodates those providing assistance. The broader architectural landscape often falls short of this, lacking the empathy and sensitivity that HomeGround so seamlessly integrates.

HomeGround proves that human rights can be upheld without sacrificing revenue or aesthetics. Instead, it achieves this through smart design choices that translate human rights into practical, tangible solutions. There is a pressing need for human values to be integrated into architecture, as these play a fundamental role in upholding essential rights. The contrast between legal frameworks and real human experiences highlights the importance of bridging this gap, ensuring that laws are not detached from lived realities but instead inspire and drive positive change.

As Kassahun's puts it: "For the sake of our communities and our future, let’s stop mindlessly constructing and start talking about how we can build mindfully. Human rights and architecture must be intertwined if we are to create cities where people can thrive, not just exist."

FURTHER READING

Tiziana Panizza Kassahun's book Architecture & Human Rights explores the critical relationship between urban design and human rights, highlighting how architecture can be a tool for creating social justice and equity. The book is a collection of narratives, photos and conversations that address the challenges posed by rapid urbanisation and growing inequalities in living conditions. Kassahun argues that architecture should not only focus on aesthetics or functionality but must also consider the human rights of the communities it serves.