In this globalised age, we carry labels with us everywhere and at all times. We carry them when we start school, a new job or a new relationship; when we pack our bags and move cities, countries or continents; and when we send out a tweet, set our Instagram bios or use a hashtag.

In these and other areas, labels are used in a multitude of ways: to define ourselves in relation to others; to find others like ourselves (or to establish who is not like us); and, in perhaps the most salubrious use, a label can help us to understand another’s needs better.

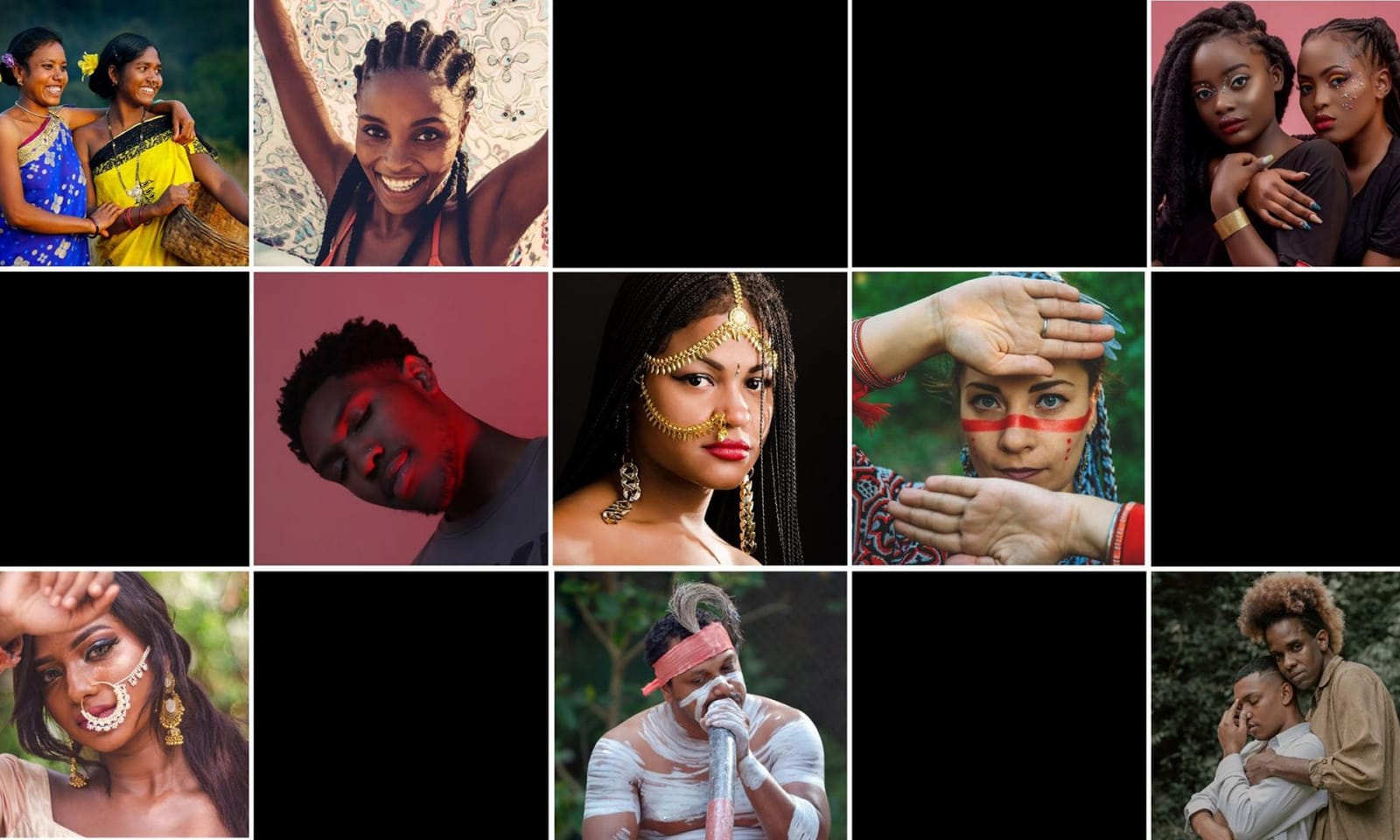

The seven billion or so people on the planet fall under the umbrella of humanity. To be human distinguishes us from the animals and plants of Earth, or the aliens of space. Within the humanity umbrella, labels are used to determine who fits where. The names we carry, the colour of our skin and the country we call home both divide and unify us. How we identify (or are identified) culturally and racially plays a big part in how we experience the world.

* * *

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by police. The evidence of his murder went viral and leapt across oceans via social media platforms. It would be ignorant to say Floyd’s murder sparked a global awakening. The recognition of the police brutality used against Floyd was a realisation predominantly for White people. People of Colour, especially Black people in America, live this every day of their lives. They have shouted it from the rooftops and White people simply haven’t listened.

Alongside the outrage on social media, the term ‘BIPOC’ took centre stage after seven years of living in the peripheries. #BIPOC began to trend as a label and as a call to action. But what does it mean, how useful is it and where does it come from?

As an acronym, ‘BIPOC’ stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour. Fundamentally, it is rooted in the legacies of the United States. Like ‘BAME’, the United Kingdom’s aged but arguably equivalent term highlighting the experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnicities, ‘BIPOC’ draws specific attention to the experiences of Black and Indigenous people in the United States.

In an interview on the Brian Lehrer Show, Jonathan Rosa, a sociocultural and linguistic anthropologist at Stanford University explains the context of the term ‘BIPOC’: “I think for many people, ‘BIPOC’ is a way of saying ‘wait a second, we live in the afterlife of slavery; we live in the afterlife of genocide, and so these are ongoing histories. They are not just 300 years ago; they are today, and we can see their legacy across a whole range of institutional dynamics. ‘BIPOC’ is an attempt to stake a claim to the ongoing legacy of those systems.”

The legacies Rosa talks about can be seen in the systemic injustices embedded in the daily lives of Black and Indigenous people and can be anything from discrimination in the criminal justice system (George Floyd, Breonna Taylor or the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women) to name alteration when applying for a job.

“The conversation we are having today is part of a long-standing history that, I think, is attempting to address or attempting to conceptualise and enact solidarity, while also thinking about the specificity of [a] population’s experiences. And that tension between solidarity and specificity is what’s at stake here,” Rosa explains.

While for some ‘BIPOC’ is being seen as a reclamation, for others, it is simply a rebranding of the same old story. Black, Indigenous and People of Colour have been called a variety of names since White people first landed on their shores.

According to the New York Times ‘BIPOC’ was first mentioned on Twitter in August 2013. The term is a successor to the label ‘Person of Colour’ (POC) which was first recorded in 1796 in the American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. POC was initially used to refer to light-skinned people of mixed African and European heritage and, as time went on, came to differentiate between those who were enslaved, primarily Black people, and those of mixed heritage, who were free from slavery. The term evolved again after the American Civil War, becoming ‘coloured’, and was used widely to describe all Black Americans.

As the Civil Rights Movement took hold of America through the 1950s and ‘60s, a cultural shift occurred. So far, White people had determined what Black people were called. This time Black people chose their own identifiers. The term ‘Person of Colour’ (POC) emerged in opposition to the previously used label ‘coloured people’. POC was intended to create solidarity between marginalised groups through utilising person-first language—a linguistic method that describes what a person has, not what a person is. Central to this was the fact that Black people were able to choose their label for themselves rather than having White people decide for them.

The term Person of Colour, then and today, primarily refers to any person who is not considered White. Of course, this remains largely within the context of the United States of America. African Americans, Native Americans, Latinx Americans, Asian Americans, Pacific Islander Americans, Middle Eastern Americans and multiracial Americans are all included under the umbrella term. It is a label which counters the expectation of Whiteness and creates solidarity but also carries with it the potential for erasure.

“Any of these labels in a given moment might be politically useful and productive from some vantage points but might be erasing or marginalising someone else’s experience from another perspective,” Rosa explains. “This is what we were grappling with: how it is that a certain moniker or a certain acronym allows us to specify particular realities or particular relationships while also obscuring other realities.”

The individual experiences of those who fall under the POC moniker are highly dependent on their cultural and ethnic backgrounds. While the term ‘BIPOC’ has the potential to push back against the homogenisation of the term POC, it still does not account for the myriad experiences of people who identify as Persons of Colour. This is why it is so integral to understand the etymology of terms like BIPOC and BAME, especially when it comes to using these terms in our day-to-day lives. Who exactly are we talking about?

A term like BIPOC has a time and a place, but fundamentally we need to recognise that there is more to the acronym than just a series of letters representing words. When the term BIPOC is used, it is used in reference to human beings. Human beings who have the right to determine how they want to be known. So, listen.

Gabby Beckford, an award-winning Gen Z travel influencer and Opportunity Expert behind the blog Packs Light, says that when it comes to a person’s labels, it's important to listen to those who identify as Black, Indigenous or as a Person of Colour.

“Black people are classified and reclassified so often that it can feel like we are being recategorised like books and other objects,” Beckford explains. “Some Black people say that they prefer to identify as generally Black or as ADOS [American Descendants of Slavery] or African American or any other terms... I think that’s the important distinction for those looking for guidance on what is the “right” term to use—you can never be too specific, but to generalise (especially incorrectly) can be hurtful. When in doubt, be as specific as possible.”

What is the importance of specificity? It’s about making clear the different issues faced by different groups. Every ethnicity faces a distinct form of discrimination at the hands of White supremacy. A Black person’s experience overall is entirely different to that of an Asian person; an Indigenous person’s experience is entirely different to that of a Black person; and so on. While ‘BIPOC’ calls awareness to the Black and Indigenous experience, not every situation refers to all included under the umbrella.

“The term BIPOC—and other generalising terms like POC and BAME—are essentially saying ‘non-White’ or ‘other’,” Beckford explains. “There are times when it might be appropriate to classify people as such, but it’s a rarity and not as often as most may think. I will always encourage those in question to forgo the trendy terminology and stick to the specific basics. When in doubt, ask ‘What’s the most respectful way to refer to you?’ or ‘Can you tell me how you identify ethnically? I don’t want to misspeak.’”

Mae M. Ngai, an historian and author of Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, also explains this concept in an article for the New York Times: “You should call people by what [they] call themselves, not how they are situated in relation to yourself.” Though here she is referencing the term ‘Oriental’, an “antiquated” term for people of Asian descent the sentiment remains true.

‘BIPOC’ is a product of the times. It recalls the history that led the United States of America to the place that it is today—the reasons that George Floyd and Breonna Taylor’s murderers are yet to be convicted and why White supremacists have no fear of police bullets as they ransack Washington DC’s Capitol, bearing confederate flags. Does #BIPOC have the power to bring us together as we overthrow oppressive systems? Perhaps. Though there is more to it than that.

“None of these acronyms will ever solve the problem of racial justice by themselves,” Rosa surmises. “They are more of a reflection of where we are in a given moment and how it is people are making sense of the struggle. BIPOC is a tool, or any of these acronyms are a tool, for engaging in broader struggles; they are not solutions by themselves.”

‘BIPOC’ is not a perfect term; it will probably be replaced by a new iteration in the future, but for now, it is what we have. Its story begins with the Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour who make up the United States, but its message is one that resonates across the globe. The term speaks to the experience of BIPOC individuals worldwide who have grown up in societies that centre around Whiteness and so cannot be underestimated for its ability to establish solidarity between those long positioned as ‘other’. Nor should it be discounted for its ability to give people a voice. However, who is and is not ‘BIPOC’, and the challenges and experiences of BIPOC should always be decided by those who identify as Black, Indigenous and/or People of Colour.