In the age of social media, we are all just one click away from sharing who we are or what we stand for.

We could be reposting our grandma’s cookie recipe one minute and tweeting about the Myanmar coup the next. Social media can be at once humorous, uplifting, divisive and destructive. It’s no wonder that it can be difficult to navigate this vast digital sphere of communication. With such ever-changing terrain, where does one position oneself to do the most good and the least harm?

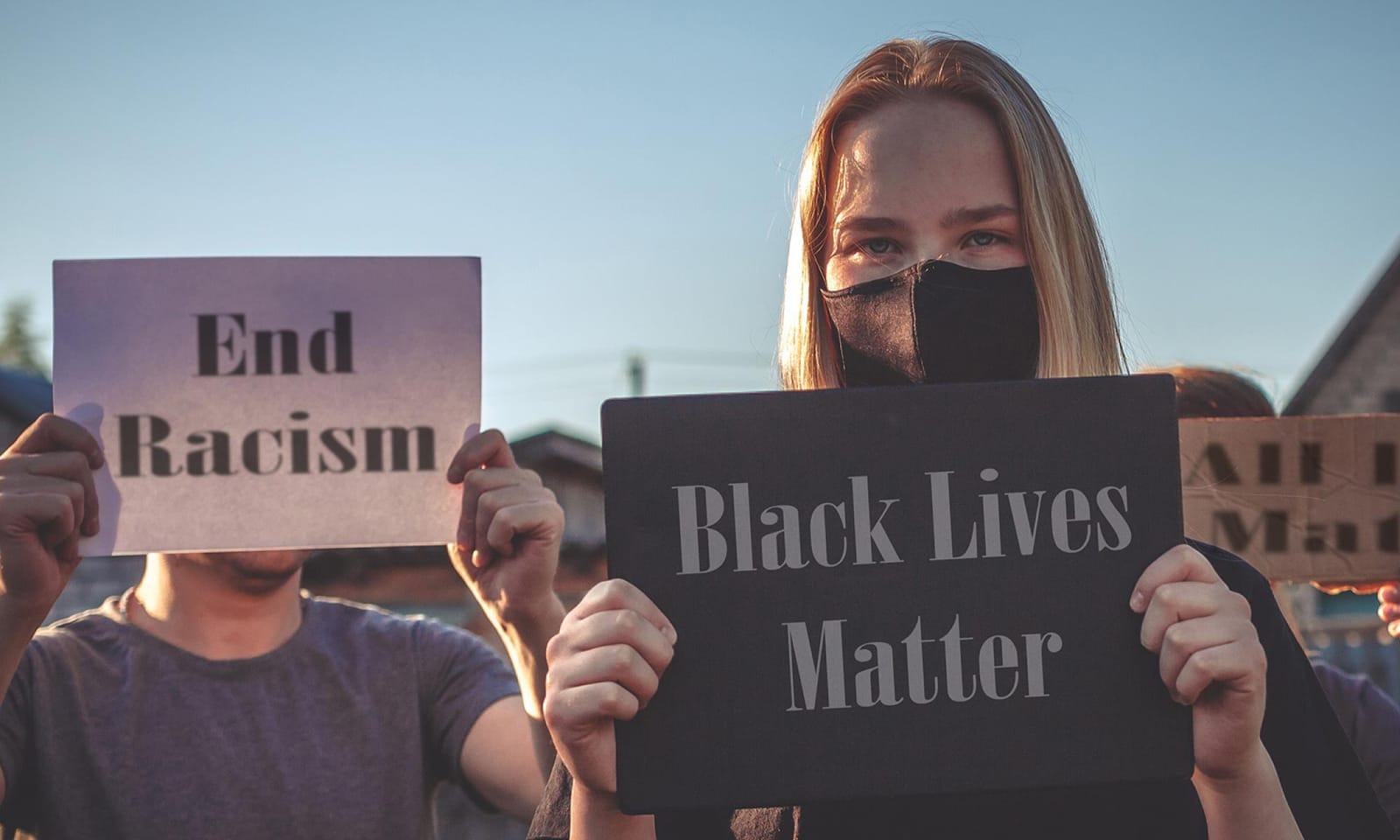

The question of ethical use becomes even more significant when applied to social justice movements that depend on platforms such as Instagram or Twitter to thrive. One movement in particular, Black Lives Matter, has united people through social media in their mission to eradicate White supremacy and protect and uplift Black lives in the process. However, White allies, or individuals standing in solidarity with the Black community, have at times misdirected or thwarted the cause they intended to promote.

This was perhaps exemplified by the Blackout Tuesday phenomenon, in which Instagram users posted black squares alongside hashtags such as #blm or #blacklivesmatter. The trend to demonstrate allyship backfired miserably: instead of promoting awareness of the murders and systematic oppression of Black people such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, these black squares bogged down accounts and feeds crucial to the Black Lives Matter movement. Accounts using the same hashtags found it difficult to share pertinent news, such as posts that informed activists on how to stay safe during protests that were all too often shut down by police brutality. Even well-intentioned posts can be destructive, meaning that one must tread carefully online. Lakshmi Sarah, an American journalist, producer and university educator, puts it best: “If you don’t know where a trend comes from and you’re participating in it, you might perpetuate something you don’t intend to. Sharing a social media trend that you think is great can actually be detrimental.”

Sarah, who has lectured at various universities across the United States and produced content for numerous platforms including AJ+, KQED and The New York Times, says the social media landscape has drastically changed over the years. Part of that is due to the rise in usership. Merely two years after she began teaching courses on social media journalism in 2016, the number of monthly Instagram users had skyrocketed from around 400 million to 700 million worldwide. Today, in 2021, the number has grown to approximately 900 million, showing the potential reach of a single Instagram post or Tweet. Sarah acknowledges that this means, in some ways, social media has the capacity to affect positive change on a large scale. “Movements can more readily share information,” Sarah says, “which I would argue is a good thing.”

However, Sarah points out that “hashtags can get co-opted.” Others have voiced this concern as well. In a video titled “How To Be An Ally: Here’s what white allyship really looks like,” Black panellists address the problem of the point-and-click, reflexive approach to allyship on social media, citing Blackout Tuesday as an example.

“It makes me angry,” says Maria McDowell, one of the panellists in the video. “It demeans the whole thing. There’s so much more to be done; there’s so much more to racism than posting a black square.”

Journalist Jordan Jarett-Bryan adds, “I think we’re past trying to feel good as a group. It’s time to take action . . . People aren’t dying on social media. People are dying around the corner from where I’m living. When Black men and Black women are being murdered, I’m past trying to feel great because we’re ‘in this together’. It’s more than that for me.”

Both speakers touch on the same point: the hollow display of solidarity, devoid of any true action towards dismantling racism—also known as ‘performative activism’—is an insidious and pervasive problem among White allies. It is also a behaviour that undermines or obscures other causes. Sarah references a KQED piece by Rae Alexandra titled “Empowerment Selfies Are Burying A Turkish Women’s Rights Campaign,” The article addresses the viral Instagram trend in which women were “challenged” to post a black and white photo of themselves with hashtags such as #womensupportingwomen. However, upon further investigation, Alexandra discovered that the original purpose of the challenge was to bring awareness to the staggering rates of violence toward women in Turkey. Though the campaign was intended to promote solidarity while highlighting the oppression of women, Instagram feeds became flooded with selfies that provided little to no context, essentially drowning out the initial message.

If you have engaged in some form of performative activism on social media, you’re not alone. The phenomenon can be partly attributed to the ways regular social media use can affect human psychology. Sarah notes that documentaries such as The Social Dilemma “hit home for a lot of people in terms of what social media is training your brain to do . . . you want that little [notification].” This reward cycle, in tandem with the genuine desire to be an ally, can be a harmful combination. “There’s a false equivalence between meaningful change and how many views, shares or likes a post gets,” Sarah says. “I think there’s a tendency for a lot of people to see social media as, ‘oh, if I like this post, or if I share it, then I’m done.’ Liking or sharing information doesn’t take it to the next level.”

So how does one become a true ally? Sarah states that performative activism in social media can “make you feel like you’ve done the work,” but that “the real work is done between people. It happens at, for example, city council meetings. You can’t cut corners.” Furthermore, think before you post. “Thinking before you post is the very basic thing to do,” she says. “Before you post, like or share . . . ask yourself, ‘how might this be perceived by somebody who is different from me?’ or even take the more journalistic approach by asking, ‘how would somebody else read this?’”

Sarah acknowledges that ultimately, it can be difficult to differentiate meaningful online activism from performative allyship. “It’s just such a complicated world now with social media. I feel like we don’t really have all the answers.” However, Sarah looks forward to a future in which we can think more critically about the role social media plays in our lives and adds that many of us have already begun. “I think that people are starting to understand what the impact is on their immediate life and people and things around them, both politically and personally.”

We can all benefit from examining our personal engagement with social justice causes on platforms like Instagram. At the very least, missteps such as Blackout Tuesday have taught us valuable lessons. A cute photo of a puppy can be shared on a whim, but a post regarding social justice deserves serious thought, research and action. Social media posts can be a great start to the conversation about ending racism. They cannot be the conclusion.