In Southern France 1940, a young boy and his friends stood at the entrance of a deep 15-metre hole in the ground.

They believed they had found the lost passageway to the nearby manor house; in actuality, they had discovered a complex of caves. Across the cave’s rocky interiors, the boys uncovered over 2,000 paintings and engravings, representing massive beasts, mythical creatures and abstract signs. Experts believe the cave art to have been painted by generations of artists around 17,000 years ago. A time when mammoths, sabre-toothed tigers, and giant ground sloths larger than today's elephants still roamed the plains. A time when our ancestors began progressing their cultures and artistic skills and recording what they saw on the ground around them. At some point, they turned their sights upward to what they saw written in the stars.

On these walls, amidst the countless paintings and engravings, there features a depiction of a bull with six dots resting just above its shoulder. It is the precise nature of this rendition, with the careful placement of the dots, that has caught the attention of astronomers and anthropologists alike. These dots are thought to be the earliest depiction of the Pleiades, a relatively insignificant cluster of stars lying 400 light-years away to the north-west of the Taurus (’the Bull’) constellation. Perhaps you know the Pleiades as the Seven Sisters or as Matariki, Subaru or Kartikeya; maybe Mao, Hoki Boshi or Kungkarungkara. Across the globe, countless cultures and civilisations have a name for this cluster and a story to go with it.

To find this small, tightly clustered group of stars, look first for the belt within the Orion constellation—one of the most recognisable constellations in the sky. This is made up of a line of three stars, whose closeness and brightness are unseen anywhere else. If you are in the Southern Hemisphere, follow these stars in a line from right to left—if you are in the Northern Hemisphere, left to right—and you will find a triangular-shaped cluster which is the face of Taurus the bull, also known as the Hyades (the half-sisters of Pleiades). A little further on, you will notice a small group clustered tightly together—this is the Pleiades. Or, to the scientific community, Messier 45. Some of you will see six stars, some more, some less.

The Seven Sisters by artist Marije Berting

Our obsession with the Pleaides is well recorded in literature. Mentions of the cluster first appear in the Chinese annals of about 2,350 BCE, followed later by Hesiod's Works and Days, the Geoponica, and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. There are three references in the Bible, with one passage (Revelation 1:16) describing a vision of the coming of the Messiah holding seven stars in his right hand. Some scholars believe them to be the star mentioned in Sura An-Najm (‘the Star’) of the Quran. Even the 19th-century British poet, Tennyson, found himself drawn in by the majesty of the rising cluster, penning the sweet couplet:

“Many a night I saw the Pleiads, rising thro’ the mellow shade,Glitter like a swarm of fireflies tangled in a silver braid.”

These stars have enchanted our ancestors for aeons. They have been revered, worshipped and woven into the fabric of us all. The most widely recognised name for the cluster, ‘The Pleiades’, comes from the Ancient Greeks. Named for the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas and the Oceanid Pleione, sailors used the stars to determine the best times for journeying the Mediterranean Sea. For the Japanese, the stars are Subaru, meaning 'gathering together', symbolising fertility, planting and harvesting, alongside the changing of seasons. For the Vikings, the Pleiades were thought of as Freya's hens. While in Hindu tradition, they are Krittika, representing the seven daughters of Brahma and Savitri, who married seven wise men. Across the ocean, the Kiowa tribe of North America recount the legend of seven maidens transported into the sky by the Great Spirit to save them from the giant bears chasing them. The Spirit created Mateo Tepe (known more widely as the Devil's Tower National Monument in Wyoming), a butte which placed the maidens beyond the reach of the bears. When the bears began to climb the sheer cliffs, the Spirit lifted the maidens even higher. Today, the maidens rest safely in the sky, while the markings of the bear's ascent can be seen in the striations on the side of the magnificent rock formation.

Milkyway over Devil's Tower, Wyoming

For most of us, when we look at the cluster without some form of magnification, we see six stars, maybe a seventh if we squint. For thousands of years, the known number of stars was dependent on where you were in the world, the varying degrees of light and air pollution, and of course, how good your eyesight was. Within ancient cultures, the number of stars recorded has varied between as little as six, to as many as 16, with the Prophet Muhammad said to have seen 12. It was not until the early 1600s when Galileo Galilei first observed the Pleiades through a telescope that the true nature of the cluster was realised. While he was correct in concluding that there were many stars too dim to be seen by the naked eye, his official sketch was still way off, depicting a total of 36 stars. There are in fact several hundred stars. We did not know this when we began to tell our stories.

Pleiadean lore is a direct response to what our ancestors saw written in the stars above. Almost every time, the stories return to the number seven. There are many tales, echoed across the globe from Australasia to the Americas, revolving around the plight of seven young maidens, who are part of an epic chase which begins on the earth before they can find safety in the sky. Typically, the motivation for the pursuit is that a man, or men, desires the women. In the Pitjantjatjara Dreaming story, an evil man called Nyiru, or Nyirunya, chases the sisters, the Kungkarangkalpa, up into the sky, down to Earth and back into the stars again, until eventually, the sisters are transformed into the Pleiades cluster. At the same time, Nyiru assumes the form of Orion, forever immortalising their chase. It is interesting how closely this story is echoed in ancient Greek legend. One version tells of the famous hunter Orion chasing the seven sisters for seven years until Zeus finally answers their prayers for safety, turning them into birds and placing them amongst the stars. These cultures never met, yet what they saw written in the stars was somehow transposed across distance and time.

When it comes to understanding why there is such a focus on the seventh star when most of us can only see six, you'll find many explanations out there. Some believe that one of the stars has genuinely lost its brightness with time. Others argue that astronomical evidence suggests a once visible star in the cluster became extinct around the end of the second millennium BCE. Perhaps this could explain the Greek myth which claims the missing star is Electra, an ancestress of the royal house of Troy, who, overcome by grief when the city was destroyed, abandoned her celestial sisters by transforming into a comet. Or why the Indigenous people of Japan, the Ainu, now only speak of Six Lazy Sisters when they once spoke of seven.

The Pleiades are so deeply woven into our societies that in many instances, their influence is so subtle it is barely noticed. They have been built world-over into the foundations of cultures and civilisations, past and present. Some claim that the Great Pyramid of Giza is oriented for the rising and setting of the Pleiades. For the ancient Druids, the cluster signified the end-of-October festival of Samhain, which marked the end of the harvest season, the beginning of winter and the Celtic New Year. The modern Halloween is said to have resulted from the merge of Samhain and the Christian celebration of All Saints’ Day. Across the oceans, the Mapuche of South America also began their New Year when Ngauponi (their name for the Pleiades) rose before the Sun, representing the birth of new life.

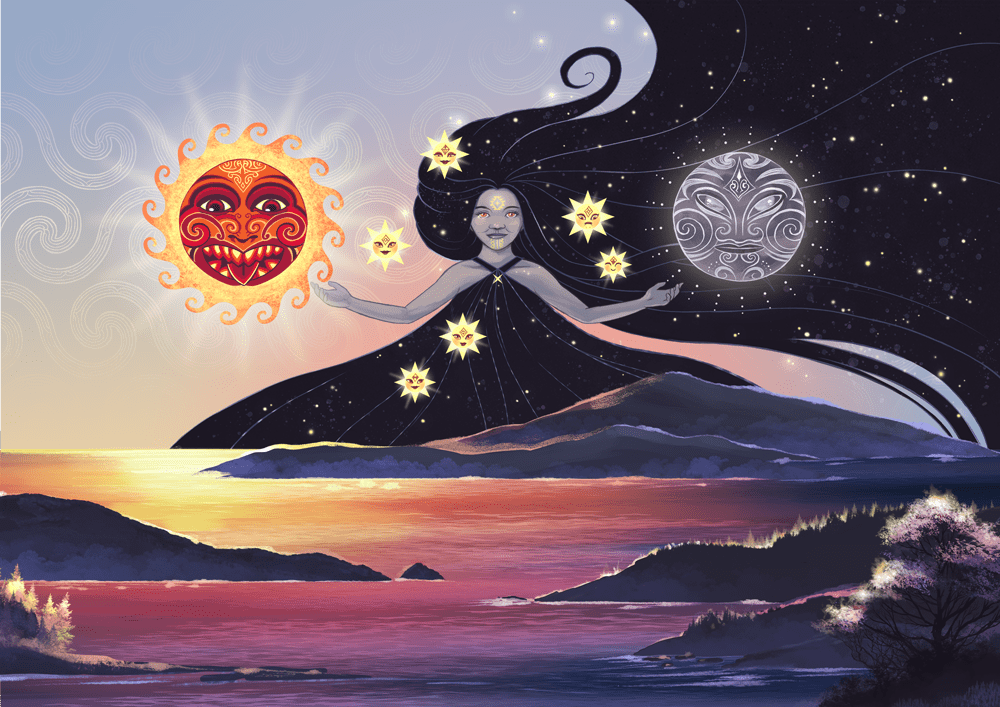

Matariki illustration by New Zealand illustrator Izzy Joy

In the Pacific, the rise of Pleiades in the winter months also symbolised the beginning of the New Year. Like the Celts, the appearance of Matariki for those in Aotearoa, New Zealand, occurred at the end of the harvest season and was an important time for festivities. The brightness and clarity of the stars were seen to indicate the success of the oncoming growing season and used to determine when planting should go ahead, as seen in the following saying:

"Matariki atua ka eke mai i te rangi e roa,E whāngainga iho ki te mata o te tau e roa e."

"Divine Matariki come forth from the far-off heaven,Bestow the first fruits of the year upon us."

It is during these celebrations that traditional Māori kites (pākau) were flown in an effort to bring the people closer to the stars. It seems that no matter where we settled, our ancestors were always looking upwards. For centuries, storytellers have carried our fascination with the Pleiades, passing the stories down generation after generation.

Around 17,000 years ago, an artist painted a set of six dots above a bull depicting a relatively obscure cluster of stars on a cave wall. Why? While there isn't a single answer to that question, one thing is certain, the Pleiades have connected us through space and time. Within the night sky, we saw heroes, we saw villains, and we saw our sisters. We found answers to our questions and guidance when we lost our way. At some point, for some reason, almost every culture and civilisation found meaning within this same cluster of stars. Meaning that continues to resonate across the globe.