In the face of the many seemingly unsolvable problems of the world, it takes courage, faith and determination to take on the role of a superhero. Colours Of A Changemaker is a series of interviews with Black, Indigenous and People of Colour from around the world who are using their vocation to create social and environmental change. As Gandhi once said, we must be the change we want to see in the world, and these changemakers are doing just that through their art, music, written works, social platforms and much more.

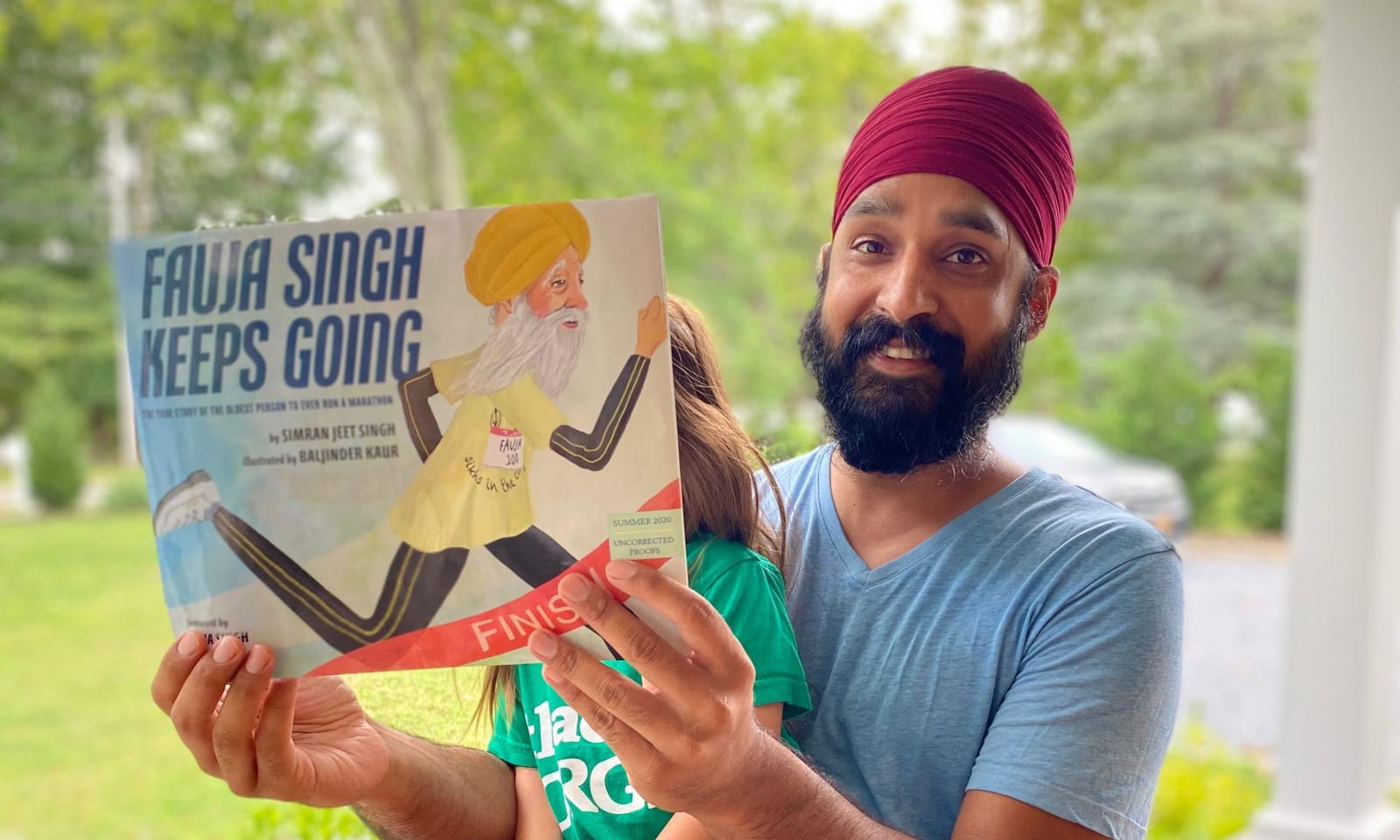

I interviewed author, scholar, teacher, and activist Simran Jeet Singh. Born and raised in the only Sikh family in southern Texas, Simran Jeet Singh would look for heroes that looked like him in local bookstores—only to be disappointed. That childhood longing to be seen and represented remained unfulfilled for years until he came across Fauja Singh, a British-Punjabi runner who became the first 100-year-old to complete a marathon. His life story moved Simran Jeet Singh to write Fauja Singh Keeps Going: The True Story of the Oldest Person to Ever Run a Marathon, an illustrated children’s book that breaks our preconceived ideas around what a hero should look like. The book, published by Penguin Random House (Kokila), is the first children's picture book by a major publisher to centre on a Sikh story. It is also an Amazon best-seller in both the United States and Canada, proving that the world is changing and that diversity is finally being embraced.

We’re here to talk about your book Fauja Singh Keeps Going. I’d love to start with how you came across Fauja Singh, and how he has inspired you. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Yeah, sure. I think my first point of contact and interaction really came when I was an adult. I was in graduate school—I was studying at Harvard University—and I was watching TV, and there was an ad that came on TV, and it was a few of my favourite sports heroes: David Beckham, the football player, Muhammad Ali, the boxer. And then I see a small man in a turban and a long white beard who was running, and I couldn’t believe it. I was shocked [because] in this country, we don’t really see people who have that appearance being presented in a positive way. So seeing him on TV really surprised me. Also, I had always been a big sports fan growing up, so I was really excited to see a turbaned Sikh athlete. So, as soon as I saw him, I needed to know more about who he was and what he was doing, and that’s really how I came into his story. And the more I learned, the more I loved because I learned pretty quickly it’s not just a story about an amazing person who has done amazing things but also a really inspiring story on different levels that can really help all of us connect with different experiences and develop more compassion and empathy, and that was the most exciting part of his story for me.

Can you tell me about the first time you met Fauja Singh? Perhaps you can share something memorable from your conversation with him?

Oh, yeah, lots of things. The first time I met him was actually a remarkable experience because it’s not often that you put someone on a pedestal and have really high hopes for them as a person, and then you meet them and they meet those expectations. He was exactly the way that I had dreamed him to be: very kind and compassionate, and energetic and funny. I mean, he was just smiling and laughing the whole time, it’s amazing. He was 104, I think, when I met him, and he was just in such great spirits. So that was great. We talked for about only 15 minutes or so, and I was just trying to learn from him what I could. One of the things that really stuck out from that conversation: I asked if he had any regrets in his life, and he said the only thing he really regretted was that he didn’t feel like he did enough to inspire young children, and so that really stuck with me, because he seemed so sincerely sad. I could see the pain in his eyes. But also, realising now that I’m able to help him realise that dream at a time when he felt like he never would—that’s been really powerful for me.

Amazing. And so you wrote a children’s book about him. Why did you choose the children’s book format over other formats?

That’s a good question. I think I did consider writing other kinds of books, and I would still like to, but I guess the reason it felt so urgent to do a children’s book is because I had kids of my own in 2016. The second time I met Fauja Singh, my daughter was just born, and I kept thinking to myself these are the kinds of stories that she needs; these are the kinds of values she needs to learn. Thinking about how important these books are for shaping our children and yet, how little attention we give these books, how much is missing in these conversations and what we really want to be finding for them, I realised that I had to write the book that I wanted my children to have. I think that, to me, was the most important reason for starting. And more generally, we don’t do a very good job talking to our children about difficult subjects. We don’t because it’s hard—it’s not easy to talk to our kids about disability or immigration [or] all these other challenges that we encounter in life. But I think we can all agree that we’re not really setting them up for success if we’re not talking about these, and the easiest path is not necessarily the best path. So I wanted to figure out a way to open up these conversations so that parents could expose their kids to these experiences and, in doing so, open up conversations with their own children. I’ve had that experience in my own home with my kids now, where this book has opened up those conversations, and I’m really appreciative of that.

Fauja Singh is not the typical hero that one would normally find in a children’s book. I actually got to listen to a read-aloud that you did, and I felt that even though he is a very different character his story is quite universal. Could you comment on the universality of Fauja Singh’s story?

Yeah, I think there are two ways to think about it. I think the first is—because of our assumptions of who is relatable—we always think of the people who look like us as being the most relatable, and while that’s our expectation, the reality of our experiences is that we just relate to the people we connect with because we relate on a human level. That’s what happens with Fauja Singh’s story, and I think that’s why it’s so powerful. You have this person who seems so different—he’s older, he has brown skin, he’s an immigrant, he doesn’t speak English—all these things that you see as being different, and then you hear his story and you say, “oh, his story is actually so much similar to mine in different ways.” And it’s not necessarily that we have the exact same experiences, but I think what’s universal here is our experiences of life: encountering challenges, working hard to overcome them and finding joy through that hard work and through our resilience. I think that’s what Fauja Singh does over and over again, and bringing forward the truth of his experiences—that it’s not just that you have one challenge in life, you overcome it, and everyone lives happily ever after, but instead, it’s the ups and downs of life that we all experience and really human pain of feeling isolated—I think those [are the things that] feel really relatable because we’ve all been there; we’ve all experienced that personally.

In a video I saw on your Instagram account, you said you were able to tackle three issues with this story: ageism, ableism and racism. Can you tell us a little more about that?

Yeah, those are three of the big ones. But there are more that come up the further you dig into his story that aren’t completely apparent. So, for instance, you know, Fauja Singh grew up as a Punjabi farmer, and so for him to be in a village in Punjab and for him to be of a working-class background is really thinking about what does it look like for our heroes to be challenging our assumptions on classism? There’s [also] literacy: because of his disability, he never got to go to school; he never learned how to read or write. So that was a really important one for me. Just through him, I challenge my own assumptions around intelligence and literacy and who deserves respect. And so I think there are those that you mentioned, and then there are a bunch of others. Mental health is a big one: it doesn’t come out as explicitly in the book, but he underwent significant depression after his son and his wife died, and it was really hard for him to move to England and not know anybody, but also to have lost his family. So yeah, I think you’re right, that those three are the ones that come up most immediately. But the more I dig into his story, the more these kinds of things that I bring up, because I just learn so much from them.

And that’s what makes it universal.

Right! That’s true. All of those things are, you know, you may not have one of those experiences or all of those experiences, but you probably have at least one.

How did you feel when you realised your book was going to be the first children’s book from a major publishing house that featured a Sikh protagonist? Did you feel any pressure?

Pressure is probably not the right word. Definitely, I felt a big responsibility that I wanted to get the story right in terms of how I represented the community, but I especially felt a responsibility to capture the story in a way that Fauja Singh himself would feel proud. So I actually worked with him quite a bit to make sure that he was happy with the way his life was presented, not just in terms of accuracy but also in terms of what he felt the big moments were, what he felt some of the framing issues were. For instance, he really thought it was important he [wasn’t] painted as a victim. In the New York City Marathon where he doesn’t meet his goal, he finishes the marathon, but then he collapses. I had sort of left it at that and that was sort of the climactic moment of the marathon, but Fauja Singh said, “I don’t want people to feel sorry for me. Can you please tell them that I refused to go into [the] ambulance, and I wanted to stay with the runners?” And I thought, of course, I’ll build that into the story. It may not make for as dramatic of a story, but it’s really important to him that people see his strength of character. And so that was probably the responsibility that I felt more than any to Fauja Singh himself, because it is a biography.

But in terms of how I felt, I was so thrilled. This had been for me a dream since my own childhood: that I would bring forward a story about Sikhs. And part of why I was so thrilled was I had been told over and over again by so many people that this would never happen, that no publisher would be willing to take on a story with a Sikh character. And I was confident we would get some publisher, but to me, the biggest goal was to land with a big enough publisher that this book would be available all over the world in every library, in every bookstore. That seemed like a very ambitious goal and to have achieved that, I feel so grateful.

And so you achieved that and you got published. What was the publishing experience like?

The publishing process was great, actually. This book came to fruition with an all-South Asian team, which doesn’t happen very often at all, and so my editor—she’s desi; she’s half Punjabi—she understood what it meant to [tell] the story authentically. My agent is South Asian; the illustrator is desi. So all of us together were really able to go through this process in a way that felt really natural, and we understood what the key issues were because we’re all insiders; we all know the pain of not being represented; we know how to tell a story that resonates and depicts Fauja Singh’s life pre-partition [of India]—that's when he lived. We were able to depict the immigrants... all these things that wouldn’t have been possible without people who knew first hand what it was like. I think that’s part of why the book turned out so beautifully. But also, I think that’s why the process of it was so great, because we were all on the same page and working together. They’re brilliant. I really admire all of them.

So you’ve brought me to my next question... how did you find them? Did you go looking for them or was it all serendipitous?

For me, it turned out to be very serendipitous. It’s not typically the case. But my agent Tanusri [Prasanna] reached out to me and that was a great connection, because we really connected in terms of our values, and she’s a human rights lawyer by training. I had been looking for and talking to other agents, but I kept feeling like no one really understood, not just what I was about, but also the communities that I cared about and wanted to write about. And so that was a great connection immediately with Tanusri where I felt like she got me and she was very honest about the fact that this would be a very difficult book to sell. She had a relationship with Namrata [Tripathi, the editor] and said, “I think Namrata would appreciate the story because of her own background, and she understands the value and the importance of a story like this.” It almost sounds too good to be true, but it was a very smooth experience overall, where I feel like I was in the right place at the right time; other people had sort of opened up opportunities for me, and then these other women had created their own power and risen within their companies to the point where they could bring me in. I think I was very lucky in that regard.

How do you feel about inclusivity and diversity in the publishing world? Right now, anti-racism is a popular movement; are publishers simply cashing in or are they genuinely taking the right steps towards becoming more inclusive?

Yeah, I think it’s both at the same time. I think it is very clear—and you can look at a number of statistics that have come out—that publishing is not diverse, that power is still primarily held by White people and that people of colour, people of different backgrounds are not getting the chance to tell their stories. You don’t even need statistics to know that. I think if you’re someone of a different background growing up in this country, you know that by intuition because you’ve grown up with all this literature and you see what’s around. You see who’s whose stories are being told, whose stories are being ignored. I think that’s a really big problem. It’s a long-standing problem, and it’s not going to be fixed overnight. But I also think there are some really significant moves that these companies are taking in ways that we haven’t really seen before that demonstrate a commitment to making that change. There’s an effort; there’s a gesture; there’s a shift. And the question now will be, are these companies and institutions committed enough to sustain it over time so that there’s actually a shift in power balance? And that remains to be seen. I’m hopeful, given where things are going in this country, but there’s certainly a long way to go there.

So you talked a little about how Fauja Singh was an immigrant, and I noticed that the book is full of themes like hard work, perseverance and sacrifice. Can you talk about these themes in the context of South Asian immigrants in Western countries?

To be totally honest, I was born and raised in the States. My parents immigrated in the ‘70s, and aside from a few conversations that were relatively light, I never really talked to my parents about their experiences of living here, and I never really thought that much about it. It was through Fauja Singh’s story that I really started to get a sense of how difficult it must have been. It’s because I was really spending time with his story and thinking about how hard it must have been to move to a country where he didn’t speak the language or he didn’t really have friends and no one had time for him. And then I realised that that’s not just him; that’s so many people who move across the world, across borders into different communities and cultures. That’s when I really started thinking about it, and I started having conversations with my own parents about what that was like.

My dad came to this country with less than 10 dollars in his pocket and really had to work hard in order to make a life for his family—in a way that I never have and will never really know what that’s like. But I think the ethic and the value that’s instilled through that—even though I didn’t have the experience first-hand, I have the experience through my parents of what it looks like to do hard work, to really put in effort and to do it as a matter of survival. If you really want to take care of your family, you can’t give up and that’s been something that’s always stuck with me since childhood—since watching my parents do that every day.

Why is it important for more South Asian and other minority characters to be represented in mainstream literature and other forms of art? Why is representation important in general?

I think there’s a very common answer to that question—the term that a lot of people use is windows and mirrors and that is representation is important because it helps give a window to people to see into experiences they don’t have themselves and to really humanise difference. I think that’s important. And then the mirrors idea is you create opportunities for kids who don’t typically get to see themselves as authors of their own story to begin to imagine themselves as heroes. That’s the one that I really felt growing up. Not seeing people who looked like me being represented made me feel like maybe there weren’t possibilities for me; it’s hard to imagine what success would look like when you can’t see people who look like you in those cases and so I think those two are really important.

But I think the third thing that people don’t talk about so much is through these forms of representation and increasing representation for these communities that are not typically depicted, it does the work of undercutting dangerous and harmful stereotypes. In a context where people are quite literally being attacked physically or having to deal with hate violence and discrimination just because of who they are and what they believe, I think it’s really important that we begin to undercut some of those assumptions, and I think that’s what representation can do when it’s done right; it can really open up our perceptions of who people are, and in doing so, that can open up our hearts in ways that we can connect with people that we’re otherwise feeling disconnected from.

You’ve said that you grew up as the only Sikh or Punjabi family in your area in Texas. What was that experience like?

It’s kind of a strange thing to describe because on the one hand, it was really strange: you feel isolated and you know that nobody around knows you or gets you or connects with you, and that’s a big part of the experience. Then at the same time, it feels very normal because it’s all you really know, and you make what you can out of it. And for us, it was a very joyful experience. It’s not like we were just constantly worried about racism or hate or anything like that. Yes, those incidents happened, but for the most part, we were happy, and we were looking for happiness. I had three brothers; we were very close in age and, my childhood—if I’m recalling it—the first things I think about are playing sports. We would always be playing sports. It was so happy in that sense and then within those experiences, we would occasionally have issues, whether it was someone on another team saying something or a parent or referee saying something. Things would happen but they didn’t really define our experience. And then we had to learn from a pretty young age how we wanted to deal with those moments: if we wanted to let them make us feel angry and vengeful and bitter or if we wanted to figure out ways to look beyond those experiences and really focus on the positive, and I think that’s where we ended up focusing our energies.

You have two daughters. How are you helping them embrace their Punjabi and Sikh heritage?

That’s very very important to me and my wife. My wife is also Punjabi. She’s from Amritsar, and we made a very open commitment early on that we would only speak Punjabi with our children from childhood. So until our older daughter went to school, she only spoke Punjabi. There’s a commitment to keeping the language; there’s a commitment to keeping the connection to our Sikh faith, and so every Sunday, when there’s no pandemic, we go to a Punjabi school nearby in New Jersey where she learns about her heritage, she learns about her language, she learns about Punjabi culture, she learns about Sikh history and traditions. That’s a really important part of our daily and weekly practice that both of our kids are regularly thinking about and meeting with people from their community. On a day to day basis, she’s in school, and there aren’t any Punjabi or Sikh kids in her school, but on the weekends, we’re making sure she gets that at home; we’re making sure we have those conversations so she always feels connected to that part of her heritage.

Why was it important to you to instil that in them?

For a couple of reasons, but I think the biggest one, for me, was I personally find a lot of value and joy in my heritage—and as a parent, you just want your kids to be happy—that’s what brings me joy, and I want her to at least have a chance to access that. I think another thing is that there are some real values that are part of our culture that aren’t part of American culture and so we’re really thinking a lot about how we give our kids those values and help them cherish the things that they wouldn’t get otherwise if they were just born and brought up here. And it takes a lot of work, a lot of time, but yeah, if you think it’s important than you make time for it.

I got to learn a little bit about Sikhism recently—it’s a very interesting religion. So can you talk a little bit about Sikhism, and how it has influenced you? Also, what lessons can we draw from it to help us navigate some of the issues we’re facing in the world today?

Sikhism is the world’s fifth-largest religion. Though so big, it’s still only a fraction, a small percentage of religion in India, because there are so many people in India, but it’s about two percent of India’s population. The tradition is interesting in that it’s a unique, independent religion with its own founder and scripture and practices and ceremonies: all those things you would expect in a religion. What I really love about it is that it offers a perspective of the world that doesn’t really commit itself to identity politics. Identity is important, but according to the Sikh religion, there’s no one way of doing things. There’s no single answer to even the biggest questions in life like “how do you find enlightenment?” Our belief is you can be of any religious background and find happiness within your life—which is our goal—and I find that to be really powerful, especially in today’s world where people are constantly trying to convince one another, and sometimes killing one another, over issues of belief. I wish there was more of this kind of approach, which is that “I respect you for who you are and you can be happy and you should respect me for who I am, I can be happy.” I think that’s a really big take away from that.

On that note, you practise something called spirited activism or activism rooted in spirituality. How do you define spirited activism? What led you to it and how is it different from other types of activism?

What Sikhism teaches us is that the most important thing you can do in your life is to live your values. Anyone can have values, but if you’re not putting them into practice, there’s no point in saying anything. And what that looks like is our religion teaches us that everyone is connected, everyone’s equal and that if you truly love the people around you, then you will serve them, and that’s the idea behind what I describe as inspired activism [or] spirited activism. In today’s age, everyone wants to be an activist; it’s a cool thing to claim, and it’s really easy to claim it because all you have to do is go on Facebook or Twitter and write a few things and be angry and then all of a sudden be an activist—and I think that’s fine. But what we’re finding out is when you live life that way and when you approach activism that way, it’s not really sustainable; you’re not really going to be able to do it for very long, and more important than that, when you’re acting out of anger or selfishness or any of those things, you’re going to end up creating more harm than good. Maybe you’ll take down something that’s harmful to people, but the thing that you replace it with will also be a problem because it’s rooted in the same kinds of problems that created these systems in the first place.

What Sikhism teaches us is that as much as it matters what you do in your activism, it matters just as much how you do it. It matters what’s in your heart when you approach your work, and I don’t think that’s something we really think about very much in our society today. It’s an important point that activism is not just about trying to fix the world around you, it’s also about growing yourself, and if we were to start practising that, if we were really to become serious about doing the right things for the right reasons, our world would look so different than it does right now. That’s what I mean by spirit-driven activism, and in Sikhism and in a lot of South Asian languages, the word we use for that is sewa.

You’re a professor of religion. Why is teaching important to you? What role does teaching have in your work and your life?

For me, teaching is the centre of everything I try and do. I really think that teaching itself is a service that can help other people open their eyes to experiences they don’t have themselves and to really become more loving and empathetic. And I think that’s what education has done for me. Yes, I’ve gained a lot of knowledge on different topics. I have collected degrees from different universities. But the most important thing that education has done for me is that it’s opened my eyes to the humanity of other people. And so that’s what I try and do in my teaching and that’s why I don’t teach the things you might expect. I taught Islamic studies for a few years. Now I’m teaching Buddhist history, and my focus is really to bring attention to communities that are otherwise not seen as equal, that are seen as inferior or who don’t get representation in different ways and to really help people connect with them, to learn about them. I think that’s the work and, to me, that is an anti-racist practice, to really help people see these people for who they are.

You’ve spoken about resisting racism and injustice with love and compassion. What’s your advice on putting this into practice, especially at this time when we have so many issues going on.

It’s a tough question. I think the answer, based on what I’ve learned in my life, is you can’t really just wake up one day and decide that you want to do that. It has to be something that you practise every single day, and it’s like any kind of muscle. If you want to strengthen your muscles, you have to exercise every day, and this is true for all of our qualities as well, if we really want to lead with love. It’s not easy to live that way, especially when you deal with hate that comes your way. It’s actually very difficult, and what I’ve learned through my life is if you can exercise that muscle, if you can practise every day with the smaller things—such as just making sure that every day you’re spending a little bit of time thinking about practising, preparing yourself—then you’ll be ready for those big moments like we have right now, where everything seems impossible and frustrating and overwhelming, and you will have the muscle that you can then flex in a difficult moment. So, I think that’s probably my best advice right now.

You can follow Simran Jeet Singh on Instagram here, on Twitter here, and you can learn more about him on his website here.