In separate corners of the world sit these modern cities, built not atop but alongside their precolonial history. In West Africa, the former Kingdom of Benin, home to famed bronze plaques and an advanced system of city planning, is now Benin City, an important industrial hub of Southern Nigeria. Further West, in the Peruvian Mountains sits Cusco, former capital of the Incan empire, rich with symbols of its own history, the sacredness of its alters preserved alongside the city's architecture. Mexico City, the final in this virtual walking tour, is home to ruins from Tenochtitlan, a pre-colonial urban centre, formerly the Aztec capital, so magisterial in its formation that historians and archaeologists alike have attempted to reconstruct its pyramids and aqueducts.

The Kingdom of Benin

Fractal Walls

Situated in the southern forests of West Africa, the ancient Kingdom of Benin was once a prosperous regional trade hub. At its height, between the 14th and 19th centuries, it was a civilisation at odds with Victorian design, not defined by its isolationism, but instead informed by its role as an intermediary and point of contact. Its capital, Benin City, was governed by the king—the Oba—and abutted by a wall reported to be some four times the length of the Wall of China. The comparison is best stopped there, as this wall applied a different architectural design and was comprised of deep moats dug by the Edo people, with the excess sediment used to build up the corresponding barrier. Though the walls were demolished by the British in 1897, remnants of the Benin moat still stand in Benin City, the capital of the Edo State in modern-day Nigeria. The system of walls and moats is credited to Oba Ewuare, the most famed king of Benin, who is said to have constructed them for war purposes. The design of the city is, according to ethnomathematician, Ron Eglash, based on a fractal system—heavily relying on proportions and exact measurements. This appeared foreign to Europeans who landed at Benin's shore and had not yet encountered this form of math in their own knowledge systems.

Benin Bronzes

Perhaps the most famed of Benin City’s legacies are the Benin Bronzes. These works, many of which are now held in the British Museum, are considered to be the great representatives of early African art in the global community. They are proud proof that the colonial narrative is criminally mistaken—African societies were in fact brimming with culture, sophistication and the ability to produce magnificent artwork. Many of these bronze plaques adorned the pillars of the king's palace. They depicted the king's wealth and power and served to further glorify his influence. Their retelling of the kingdom’s rich history and artistic tradition has been marvelled at since they were first seen in Europe in the 1890s, where scholars had difficulty situating their advanced form within the colonial narrative.

Cusco

Huacas y Ceques

Some 3,398 metres (11,150 feet) above sea level sits Cusco, the former capital of the Incan Empire. Nestled in the Andean Mountain Range of Southern Peru, the city holds tight to much of its early architectural roots, with many of the original stone structures still standing and the spatial arrangement largely intact. Cusco, in its precolonial form, was divided up into quarters. Within each quarter were sectors, separated by radial lines stemming from the empire’s centre—the Haucapayta. These radial lines were pathways of unobstructed sight called ceques and were adorned by Huacas, sacred shrines deeply embedded in the Incan system of belief which elevates the natural world to the status of a great deity. The Huaca, meaning literally "sacredness" in Quechua—the native Incan tongue—is not a concrete thing; some were man-made structures like tunnels or fountains, while others were features naturally occuring in the native terrain like springs or rock formations. Since the Andean conception of the earth draws similarities to the human body, Huacas were fed, figuratively, through worship and offering, as a sign of reverence to those anointed portions of the landscape. During the colonial period, many Huacas were looted, yet their structures remain defiantly standing today and can be visited in the modern city of Cusco. Also intact are many of the stone structures—temples and homes alike—which were built for both religious and government use before the Spanish conquest. These testaments to the advanced construction techniques of the early Incan Empire line the streets just as the Huacas do, further complicating a city already replete with examples of an intricate and engrossing culture.

Tenochtitlan

El Templo Mayor

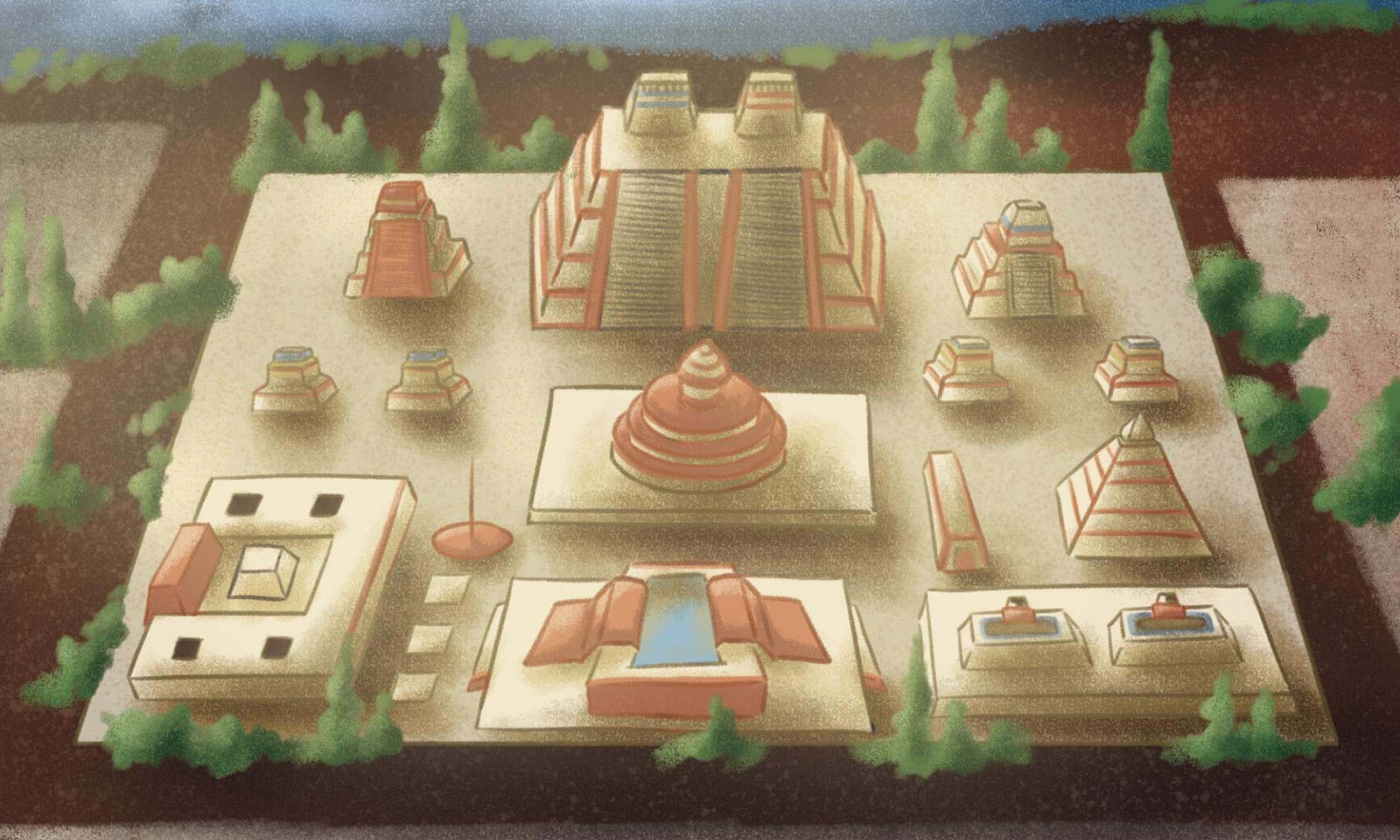

Mexico City sits atop buried treasure—literally. Sustained excavation efforts since the 1970s have rendered it a little less buried, but for many years, the Templo Mayor pyramid—the centrepiece of Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztec civilization—was hidden beneath 19th-century colonial architecture. Between the 14th and 16th centuries though, this pyramid rose opposing and grand over a bustling city. It was a temple upon a temple, with two pyramids built atop the main base, twin tributes to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, and Tlaloc, the god of rain. It was the sight of a great many coronations and sacrifices—meant to feed and satisfy the gods. Offerings and goods were buried within the many layers, built higher and higher with each new ruler. The great temple could be reached through a processional walkway and at the peak of the pyramid’s stairway, one could watch the sunrise between the dual shrine. All about the structure was an expansive wall, called the 'serpent wall' because of the great many snake carvings found within the structure. During the Spanish Conquest, the Aztecs defended the Templo Mayor fiercely, but their eventual loss to colonial forces saw the pyramid destroyed. The 20th and 21st centuries have seen its excavation, and the archaeological site sits today in the heart of Mexico City. Its phantom shadow serves to remind visitors that this was once the centre of a proud and complex pre-colonial civilisation, its public buildings, palaces and temples laid out in a carefully crafted grid, separated by canals and roadways and connected to the shore by thoroughfares raised above the water. So complex in design was the city that it is said that the soldiers who came upon it thought they were dreaming.