This piece is part of our social fiction section, which transports readers beyond the familiar, pushing the boundaries of possibility and exploring imagined futures. From the influence of technology on daily life to the dynamics of power and social norms, these stories challenge us to reflect on the world and our role within it. Some narratives highlight struggles with inequality, governance and ethical dilemmas while others offer utopian visions of a more just future. Whether set in contemporary, near-future or distant worlds, each story invites us to consider how we adapt, resist or transform in the face of challenges.

I blink to life in the mirror. Deep, harsh cracks run down the glass, the remnants of a stranger’s fragmented anger. In the reflection, the bathroom stalls stand like slack-jawed sentries, their walls crawling with the colourful consonants of people desperate to leave their mark on the world in whatever way they can. I run my tongue over my teeth, yearning for a toothbrush, and observe the red bags cradling my tired eyes with the detachment of a bystander. A siren wails outside, its cry softened by the frosted windows that have somehow remained intact in a room that feels destined for destruction. A bird hops across the windowsill. A dull ache spreads across my thighs.

My backpack, tattered and dull from the extremities of weather on the streets, is slumped against the wall. The zipper snags in the frayed fabric as I struggle to yank it open. When the zip comes free, my sleeping bag bursts from within. Tufts of white stuffing poke through the holes in the quilting and a corner drags across the filthy floor. I stuff it back inside, and the infuriating struggle reminds me of a camping trip I went on when I was a kid. A river. A rowing boat. The smell of rain on the tent’s plastic sheeting. I slip my hand into the bag to retrieve a small compact. When I open it, the powdered colours have crumbled, revealing the shiny silver of the pan beneath. Greens and blues have bled into one another, but I wet my index finger on my tongue, dip it in, and gently pat the pigment onto my eyelids, taking care to fill in the creases. The pale pink powder, soft and translucent like the inside of a shell, does little to conceal the darkness beneath my eyes. I try to resurrect the once-plump apples of my cheeks by swiping some red onto my jutting cheekbones. I set my other hand to work, scrubbing the tepid tap water into my teeth as though my skin has suddenly grown bristles hard enough to rid the enamel of its plaque.

Something vicious wraps itself around my stomach and squeezes with the intent of harm. A thin sheen of sweat prickles the back of my neck. I steady myself against the sink and try to blink away the black spots that crowd my vision. My chest heaves and I clutch for consciousness. It’s as though I’m being stripped of the will to think, to feel. I focus on the rosy-pink gob of chewing gum nestled into the yellowing plug hole, forcing myself to wonder whose teeth marks manipulated it, and whether they spat it out before or after washing their hands. If they washed their hands. The rim of dirt around the tap slowly becomes clearer with each blink.

Despite the cheap, industrial nature of the floor tiles, large fragments have come loose, shattered, or are missing completely. No one cares to replace them. I fantasise about collecting the miscellaneous triangles and forming a mosaic with them on the pavement. Turning something dilapidated and forgotten into something beautiful. The sharp smell of stale urine forces me back to the reality of my feet, splotched blue by the cold and blackened by the footfall of the public bathroom. A warm wetness seeps through my trousers.

Outside, the world screams to life on the streets. A quick-tempered driver slams the heel of their hand onto the wheel. With a frustrated tug, a businessman loosens the tie that subconsciously straightens his back and brightens his demeanour at the office. Skateboard wheels thunk, thunk, thunk over the grout in the paving stones. I look skyward and shield my eyes from the glaring white sun that bounces off a million high-rise windows like a kaleidoscope. Taxis screech to a halt, waiting for people to throw themselves in to avoid their late tariff. A dog, wheezing in the August heat, lurches towards me. I crouch to its level, charmed by the comically thick tongue lolling out of its mouth. It strains against its leash, sinewy muscles quivering for the breath that its collar restricts.

“It’s alright.” I smile. “He can say hello.” The woman yanks the dog away without a word.

I drape my only spare t-shirt over my neck as protection from the sun’s gaze on my walk north. It’s eleven blocks to the women’s shelter, and I feel every heavy step of the journey in the cracking of my lips, the weight of my rucksack painting my back with sweat, the blisters chafing my heels.

I used to keep a diary. It was filled with meticulously written schedules, future plans and career aspirations. My next goal was to get a dog; I was well over the prospect of romance and felt that a dog would be a less complicated companion. Now, I weigh up the benefits of a dog’s protection with my ability to feed it every day. I round the corner on the sixth block and almost run into the last woman in the meandering queue for the shelter. I join the queue behind her.

Ten minutes go by. Fifteen. Twenty. My feet have moved less than five metres.

“Excuse me?” I tap the woman in front of me on the shoulder, and the group she’s chatting with turn in unison. She squints at me in the sun’s glare and unashamedly runs her eyes over my hand-cut shorts and sweat-stained tank top. Although her small mouth curls into a toothy smile, when she meets my eyes, I can’t hold her gaze.

“I don’t mean to be rude,” I continue, “but could I cut in front of you guys? It’s a bit embarrassing, but I need to get a tampon, quickly.”

The group of women erupt into laughter, as though we’re students in a classroom and a sanitary pad has fallen out of my book bag.

“What the hell do you think we’re all here for?” One of them laughs and unties a jacket from around her waist, revealing a crimson stain that has completely soaked the seat of her trousers.

I resign myself to the fact I can’t wait in this heat any longer and make a b-line for the nearest fast food restaurant.

The automatic doors glide open and I release a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding. The air conditioner works its way into my scalp, along with the greasy aroma only fast food joints can conjure. The queue snakes from the counter adorned with collection boxes, past the table of colouring sheets and paper-clad crayons, and down to me. An old man manoeuvres around the tables with a bucket of grey water and an old fabric mop, his back hunched over his slowly circling figure of eight motion, only straightening his posture to smile weakly at an exiting customer or to sling a tray of half-eaten chips into the nearest bin. I’ve barely noticed my feet shuffling forward until I realise I’m next in line.

“Look, we don’t have anything going right now.”

“Oh no.” I smile. “I was just—”

“Look,” the man behind the counter interrupts. His name badge reads “Manager”. “If you come back later we might have some stuff left over.” He exchanges a knowing glance with his friend, who continues to squash patties onto the grill with a firm sizzle. An uneasy heat crawls up my neck, settling behind the powder on my cheeks. The woman behind me clears her throat.

“I just wanted a cup of water. Please,” I say.

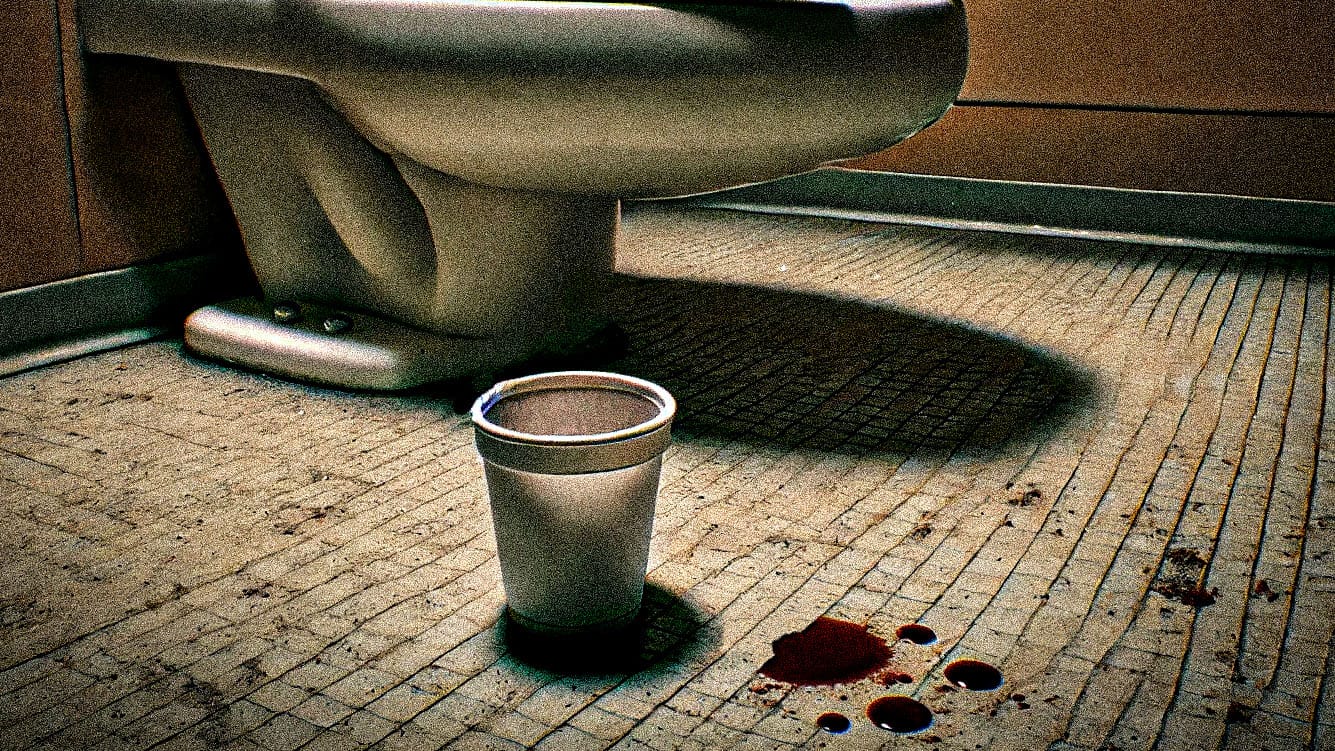

The manager unsheathes a polystyrene cup from its stack. He holds it under the drinks dispenser, letting the water slop over the sides as he checks his watch for the third time during the interaction. He sets it on the counter too firmly and begins to apologise to the coughing woman for the wait. I decide, after passing the fourth person in the queue, to look at the floor instead of their pitying eyes.

“How’s your day going?” I ask the woman leaving the bathroom stall. She nods and smiles but doesn’t answer my question and, once the tap spits out its pitiful brown stream, she strides out the door. What more can you expect from a public toilet? I hang my backpack on the back of the stall door and slide the lock closed. After placing the cup of water on the toilet lid, I tie my hair back loosely and open the front pocket of my bag. I grab a wad of tissue and raise the toilet seat lid before gently lowering my trousers to just below my knees so they don’t fall to the floor. The seat of my trousers is brown with gelatinous blood. I avoid looking down at the contents of the toilet bowl and I straddle its seat, cupping my right hand and pouring water into it with my left. Delicately, so as not to waste a drop, I bring my hand between my legs and wash myself with the cold water. My breath hitches at the first contact and I shift my weight between each foot, trying not to lose balance and touch anything in here and ruin the cleanliness of the operation. When the cup runs dry, I wring the blood from my fingers with scraps of tissue from the shoddy dispenser, too thin to wrap around my underwear. Reluctantly, I open the front zipper of my bag and grab the three pairs of socks I have. Bringing them to my nose, I try to isolate the smell of the fabric from that of my surroundings to determine which is the cleanest. I line my underwear with the selected sock and lift my trousers so it sits in the right place. I slide open the bolt with my clean hand and, rinsing the other in the sink, try to find some positivity in the fact that I can at least wring the sock out throughout the day. It's the ruthless cramps and swimming vision that can’t be helped.

Back on the street, slumped on the ground, it feels as though I’m begging for human connection more than for spare coppers. I used to think you could tell a lot about a person by the shoes they wear. Looking down at my own battered, swollen trainers now, I wonder what they say about me. Back against the wall, empty cup in front of me, there’s not much to do but look at people’s shoes. She’s probably having an affair, judging by the gait of her walk. He’s miserable at work. Her parents never taught her how to tie her shoelaces properly. After a while, it's less painful to let your head tip back, close your eyes, and allow the light to dance with the shapes behind your eyelids. Slowly, the street is diluted and I drift, like a kid in a rowing boat, to somewhere better, somewhere distant, somewhere…

White. I lurch forward with a start, gasping for breath. My muscles freeze at the mechanical beep, beep, beep of machinery that clamps my head like a vice. The sounds quicken once I realise that I’m blind.

“Where am I?” I try to shout, but the words fall out of my mouth in an incoherent rasp.

“Try to slow your breathing,” someone responds.

My knuckles ache from gripping the armrests. “I can’t see, I can’t—”

Did I get spiked? Was it heat stroke? The cool, clinical plastic of the chair beneath me pinches the bare skin of my thighs as I squirm. Why am I in a hospital? Did I get hit by a car?

“Is she going to be okay?” A woman with a familiar, wavering voice cries out to my left. A soft hand rests delicately on my wrist, as though trying to comfort a bird with a broken wing.

“A bit of confusion, possibly mild amnesia, is to be expected from the procedure,” a man’s voice, dripping with the detached authority of a medical professional, states. “Her vision should start to return within a few minutes.”

I try to focus my attention on the air, laden with the stench of antiseptic. I imagine what my chest looks like with each rhythmic rise and fall, my pursed lips as I shakily exhale through them. No one speaks. Gradually, a thin ring of light seeps in through the darkness, expanding with clinically timed precision. A dull aching thumps to life behind my eyes. As the ceiling blurs into focus through my tears, I find myself longing for the comfort of the darkness I’d found so oppressive just moments before. I feel as though my retinas have been wasted, like an expensive roll of film being exposed by a clumsy photographer.

“Do you feel connected to your body?” the man asks.

White flecks flicker and dance in the centre of my vision. They slowly expand, like a flurry of dust pirouetting in a breeze, a cluster of stars twinkling and winking at me through the murk.

“Miss?” he questions.

With each blink, the mass becomes clearer, and after a while, I realise it’s a chandelier, so grand in its countenance that I mistook it for the sky. The man scratches something down on his clipboard. I try to find a face for the voice, but a strap around my throat makes it impossible to raise myself more than an inch.

“It’s just precautionary,” he says. “We’ll monitor you for another hour or so, to be sure.”

A woman’s face appears above me. Her eyes are grey and shaped like almonds. They cinch closed like a dainty cloth bag when she smiles. It highlights the soft wrinkles around her mouth.

“Everything’s okay,” she whispers, running her fingers through the strands of my hair that aren’t obstructed by wires. “The doctor agreed to do this at home, to make it easier for you.”

“Easier for me?” My voice is still hoarse.

She frowns. “You know, to come back home to England, silly! To me!”

“I don’t know who you are.”

Her voice catches in her throat as though she’s been pinched. Crimson blooms across her cheeks and she looks to the doctor for reassurance.

“You said this wouldn’t happen,” she hisses, before he pulls her out of my view.

The doctor smiles down at me with his neat, bleached teeth. I feel that he must have another set behind the front ones, and another, and another, like a shark, and at any moment he might dislocate his jaw and devour me whole. He steadies himself on the arm of my chair and sits me up vertically with three swift pumps of his foot.

Through two enormous sash windows, golden evening light cascades into the room. Leather sofas draped in fur pelts and plump cushions adorn the huge living room. Portraits of strange men and women in buttoned-up suits and feathered wedding hats hang in grand, polished, mahogany frames on the walls. Outside, an old man manoeuvres his trowel around the invasive roots of a rhododendron bush, the colourful petals exploding with crimson red against the blotted sky. His boots scuff in the gravel of the driveway. Beyond him, vast, rich, rolling land meets only the occasional English oak tree before hitting the distant horizon. The green eventually bleeds into a rushing stream whose frothing waters must host an array of darting fish. Cows groan in the distance. I worry about my bare feet, about the mess they’ll make on the lovely cream carpet, but when I glance down, I find them clad in leather mary-janes and resting quite comfortably in a pair of medical stirrups.

“Where am I?” I ask again.

“You’re at home, for goodness sake!” the woman snaps, her patience worn thin.

“It’ll help if I explain,” the doctor reassures her. “My name is doctor Wren. I work within a programme called EXP.”

“What’s EXP?” I ask.

“Empathy exchange programme. The programme provides an immersive experience that cultivates more diversity and inclusion within upper-class spaces.”

I stare at him blankly and try to decipher how any of this is relevant to me.

“We were just so worried that you’d grow up sheltered,” the woman rambles. “The way things were unravelling at your school, and all those terrible incidents with the new family. The administrative board recommended the programme.”

My chest feels tight, my breathing constricted, I try to stand up but the restraints slam my head into the back of the chair. “The bathroom, my clothes, what the hell happened to me?”

“The person you were projected to is…” The doctor consults his clipboard, rifling through pages far too slowly. “Cindy Peterson, from New York. As I said, it’s normal to feel confused, or even to experience slight amnesia after the proce—”

“What do you mean, projected?”

“The procedure allows the participant to experience someone else’s life for a limited period of time. Walk a mile in their shoes, as the saying goes.” His mouth curls into a wry smile.

“Where is she now?” I don’t realise that I’m shouting until the woman, who I understand must be my mother, begins to sob.

The doctor continues. “As I said, she lives in New York.” He begins to sound impatient, his forced politeness wavering.

“So I get to wake up in this showroom of a house and she wakes up, where, on the street? You have no idea what’s happening in her reality…”

The doctor turns his back and busies himself with his papers. The woman looks at the floor.

“So you get a more ‘well-rounded’ child, and she gets nothing?” I shout.

The doctor beckons the woman and they exchange brief, tense murmurs with their backs turned to me. He begins to rifle through his black leather bag, and I hear the sound of clinking glass. He produces a vial.

“Where does the money go?” I ask.

The doctor plucks a prepared syringe from his breast pocket and begins to unwrap it with mechanical instinct. He inserts the needle into the vial.

“Does any of that money go to her, in New York?”

“Baby, you agreed to this,” the woman, my mother, pleads. “Try to calm down.”

The doctor draws the fluid into the syringe chamber. My muscles tense with a desire to flee but an inch of wiggle room isn’t enough. The wires taped to my forehead blur in front of my eyes as I shake my head in panic.

“As I said,” he repeats. “Some slight confusion.”

“I just want to help her! Please!”

“Mild amnesia is perfectly normal after the procedure, but this should ease the side effects.”

After a while, it's less painful to let my head tip back, to close my eyes and allow the light to dance with the shapes behind my eyelids. To drift, like a kid in a rowing boat, to somewhere better, somewhere distant, somewhere…