Portions of this section first appeared in Counterpunch as If The Blockade Is Bad, Does That Make Hamas Good?

We, expressing our anger and concern for the people of Gaza from a distance, can refer to Israel’s illegal occupation and blockade, settler colonialism, apartheid or the right of an occupied people to armed resistance. These are strategies as well as narratives, each leading to actions.

I choose the language of human rights and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), after many years of professional scepticism about their practical benefit. Working in places like Afghanistan, I believed that people had rights but I didn’t see their theoretical rights doing them much good. I still question the rights industry, which so easily becomes one more exercise of Northern expertise. Yet I believe that it is imperative to insist upon, and return every argument to, the human rights of Gazan Palestinians.

To use this language is to say that every person is born with equal and inalienable rights as outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (both 1966). These agreements are the foundations of international human rights law. In times of war, the value of human life underpins the rules and responsibilities of all armed parties to limit the harm done during armed conflict, as outlined in codes including IHL.

Human rights place at the centre of our frame of vision the rights of any individual and the authority that is responsible for providing and ensuring those rights. In unprotected Gaza today, we through our governments’ actions must take on the desperate task of protecting human lives.

To understand the task and its value, below I look back at human rights as a radical politics for a devalued community—a politics which distinguishes between the people of Gaza and Hamas. Then I offer a guide to the current application of human rights and IHL, which again centres on the rights of Palestinian people.

Gaza and Hamas

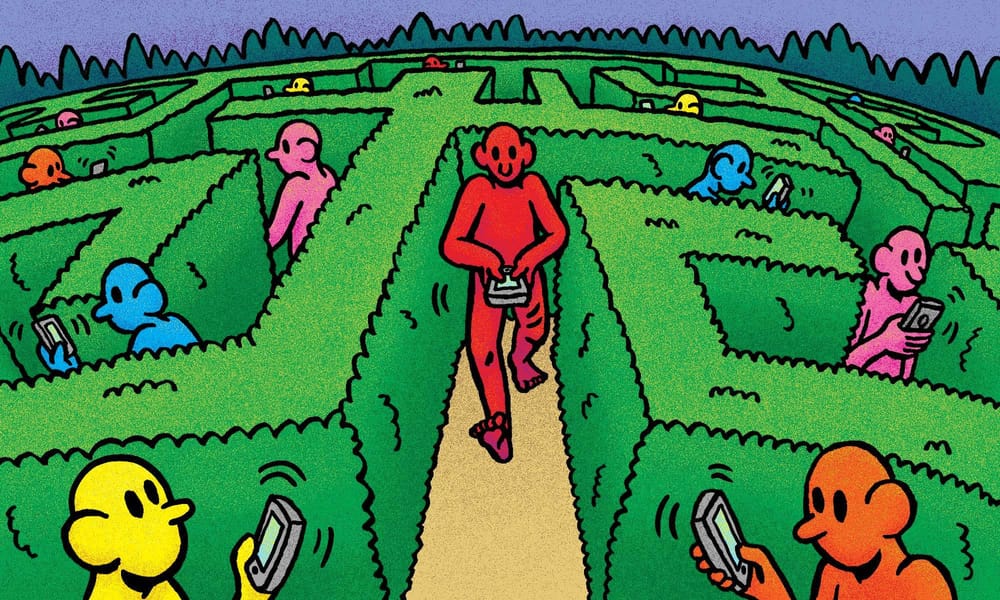

Living in Gaza (2011–2015), I came to understand Israel’s blockade as a seedbed of despair, a future-eater. Human rights best described that which Israel, the effective authority through its blockade, had chosen to withhold from Palestinians. The Gazan community had much of what it needed to thrive, including long-term social assets like education and a deep ethos of mutual assistance. Yet Gazans were avoidably denied inputs essential to their health and wellbeing; and vital building blocks for their collective social, economic and political life. Thus Israel’s occupation and blockade deprived them of their fundamental human rights.

That is a true and incomplete description.

Secondarily, many Gazans were also oppressed by Hamas. Elected in 2006, Hamas had become plain brutal a decade later, not “an expression of Palestinian resistance but of the degeneration of . . . hope that moral strategies can succeed” into something unheroic and enraged. They imposed a crushing unity. Those Gazans who were in political opposition, women, LGBTQ+, accused criminals, debtors and various non-conforming others were twice oppressed and endangered. Hamas was the lurking power that people mentioned in whispers, “Shh, someone’ll tell Hamas.”

The blockade walls ironically gave Hamas unlimited, authoritarian power to oppress. Of course they had supporters but as long as they also had a monopoly of armed power, no meaningful political contest would be permitted to test their support. Hamas fired rockets from residential streets and the neighbours slept with relatives until Israeli retaliation had passed. They shot democracy activists in the knees, such that many limped. I shuddered when they jogged in formation beneath my window in each rosy pink sunrise, their military chant drowning out the soft Mediterranean waves. In Gaza’s public sector Hamas also employed non-combatant teachers, health workers, bureaucrats and rubbish collectors. Hamas tried to govern and administer a society in perpetual resistance while being cut off from the most basic international state interactions—a fiendishly difficult task. The isolation of Hamas never did prevent them from amassing weapons. Civilian Gazans paid the price. Gazans could not post letters, carry out international bank transactions or use many major software systems because Gaza was a diplomatic and commercial non-entity.

Human rights offered a language to balance all this: human rights are the rights of the people of Gaza, not the entity called Hamas. Rights necessarily summon the responsibility of an authority. Hamas was the immediate—yet not the effective—authority over people’s lives in Gaza. They were immediately responsible as the holders of governing power. Their role is often called the de facto authority in formal documents.

However, despite Hamas holding de facto authority, Israel retains effective control over Gaza’s resources, borders, mobility and every aspect of daily life. The United Nations, Red Cross, International Criminal Court (ICC) and other key international institutions still consider that Israel occupies and controls Gaza.

How, then, to hold Hamas accountable for its actions within the messy reality of surviving and resisting in Israel’s noose?

S. Michael Lynk was the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory 2016-2022. I asked him how he balanced Hamas’s responsibility and victimhood. He replied:

"Martin Luther King Jr said, ‘It is incontestable and deplorable that Negroes have committed crimes, but they are derivative crimes. They are born of the greater crimes of the white society.’ I take King to be saying that these crimes should not be excused or justified, but they should be understood in the context of institutionalized subordination.

"The rule of law and the universal standards of human rights apply to everyone and to all situations. But saying this also means that in cases of structured subordination–where a people or a minority are kept by law and/or force in a vulnerable and oppressed situation—we must understand the context in which the violence and the counter-violence take place. Yeats once wrote: ‘I and the public know /What all schoolchildren learn, /Those to whom evil is done /Do evil in return.’"

Derivative crimes within a structure of oppression: we must account for the crimes of Hamas because we value the lives that have been affected. We must also situate those crimes within the occupation’s structure, in order to place Hamas in a meaningful evaluative category.

Human rights as radical politics

To our understanding of battered places like Gaza, human rights bring an anchor and a vision of an accountable, compassionate future co-existence.

As Richard Falk (former Special Rapporteur, prolific author and international lawyer) has noted, altering borders per se will not resolve this comprehensive conflict. “[F]or both sides the struggle is more about people than territory.” (italics in the original). A discourse of human rights keeps people at the forefront.

Because they equate the value of all people, human equality constitutes a radical politics for dehumanised Gaza. If Gazans are fully human and the value of human life is indivisible, then the choking blockade must go. The blockade classifies life ethnically and systematically diminishes the entitlements of a people: the World Health Organisation assesses that Palestinian life expectancy is nine years shorter than that of Israelis.

In a world of power politics, Palestinians are reduced to wheedling concessions within an unchanged regime of control. Rather than negotiating marginal improvements to Palestinian lives under Israeli military occupation (with extensive American financial backing), human rights reject the power to classify life. Human rights reject the structural power of blockade, not by being anti-anyone but by restoring the full, equal value of each discounted life.

When protest takes on this vision and this language, we are obligated to speak it every day: a discourse of rights also prevents us from discounting Israeli civilian lives. The racist rhetoric and the stated genocidal intent of Israel’s leaders do not rob all Israelis of their civilian status. Israel’s President Herzog has said that there are no innocent civilians in Gaza. Wrong as that is, it does not invalidate the civilian status of Israelis.

We protect the rights of the powerless with reference to the rights of all. Human rights are everyone’s rights, or they are nothing. And rights are underpinned by responsibility including the responsibilities of all armed parties in war. Occupied people have a right to armed resistance (see below) within the rules of war. However, no one has a right to unlimited violence because that would trample the rights of the people harmed by such violence.

A rights-led statement would say that, within the context of four generations of occupation, on October 7, 2023 Hamas fighters (and any others who breached the blockade wall) committed crimes and atrocities by murdering 1200 Israelis including a majority of civilians. They took civilian hostages, which is a war crime. The history of injustice and oppression contextualises but does not excuse these crimes.

Hamas’s actions triggered but, in turn, do not excuse Israel’s response which has been grossly disproportionate including the repeated targeting of civilians, protected people and objects; forcible displacement of 1.6 million people; and collective punishment by depriving 2.3 million people of food, water, light, fuel, medicines and other essentials to sustain life. The crimes are mounting and scholars of modern genocide have referred to Israel’s assault as “a textbook case of genocide unfolding in front of our eyes.”

A rights-led statement would condemn (while acknowledging the grossly different scales) all the violence that disrespects human rights and the laws of harm limitation including Hamas’s crimes on October 7, the pogroms of Israeli settlers and soldiers in the West Bank, and Israel’s actions which are prima facie war crimes or crimes against humanity. A rights-led policy would not have normalised the past 75 years of occupation.

That has been far, far from the world’s response. The United States government responded by moving warships into the region in support of Israel and allocating more billions to replace Israel’s spent ammunition. Western governments continue to respond with support that is giving Israel day after week of permission to bomb, while Gazans are spending day after week digging relatives from the rubble, looking for scarce food and water, and trying to survive.

Rights have not failed Gaza; we have. In the absence of a caring authority, the fact that endangered people have rights is not a fix. Their rights become, instead, our obligation. How can we speak, act, advocate and require our governments to act internationally, to save lives in our names?

Speaking of law in 2023: what is legal and what is not?

Before we dive into this, it’s vital to remember that individuals rather than whole societies or ethnicities are responsible for their actions in war, for the orders of battle or approvals of tactics. War is a series of individual, accountable choices. All Jewish people are not responsible for the choices of Israel’s military command structure or its politicians, while all Palestinians or all Gazans are not responsible for choices made by Hamas.

IHL is not reciprocal: the actions of one party do not release the other party from its obligations to minimise civilian harm. No one can justify this by pointing to that. International humanitarian law applies to every armed party at every moment. The statement of Yoav Gallant, Israel’s defence minister, that he has released the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers from all restraints is thus a government instruction to ignore every obligation that states have tried to put in place to limit brutality.

The following is a brief reader on International Humanitarian Law (IHL) as it applies to events taking place now in Palestine / Israel. These points are excerpted and adapted from a brief that was delivered toWinston Peters, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of New Zealand, on Tuesday, December 5, just two days before he spoke about ceasefire. The brief was prepared by Justice for Palestine and Alternative Jewish Voices in November 2023.

The first points background the current violence.

- As an occupying power,[1] Israel is required by law to act as the temporary administrator of the Palestinian territories, until they are returned in full, in as short a time as reasonably possible, to the inherently sovereign and protected Palestinian population.[2] As such, Israel is obliged under international humanitarian law[4]

- To respect and preserve the fundamental rights of the protected occupied population under international law.

- To ensure the humane treatment of the population and provide for their basic needs, including food and medical care.

- Not to transfer its civilian population into the occupied territory either directly or indirectly—to do so is a war crime.[4]

- Not to take any steps towards annexation of Palestinian territory.

- Leading international human rights organisations and United Nations bodies have reported on Israel’s repeated violation of its obligations and wider international law and human rights violations. In some instances these violations are so severe they amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.[5]

- Against this backdrop, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Michael Lynk, determined that Israel is in breach of the fundamental principles of IHL, and that is now presumed to be maintaining an unlawful occupation of the Palestinian territories.[6]

Those obligations background Hamas’s attack in southern Israel on October 7, 2023.

- The deliberate killing of Israeli civilians, indiscriminate launching of rockets into Israel and the taking of hostages by Hamas and other armed groups are war crimes. IHL requires people taken into custody to be treated humanely, and taking hostages is prohibited.[8]

- It is a fundamental rule of international humanitarian law (IHL), the law governing armed conflict and military occupation, that parties to hostilities must distinguish between combatants and civilians at all times including during all actions by Israel in response to Hamas. Civilians and civilian objects are never legitimate targets, and parties must take all feasible precautions to minimise harm to civilians. Failure to discriminate is prohibited.[7]

- The instruction from Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to Gazans to “leave now” before Israel “turn[s] all Hamas hiding places to rubble”, demonstrated intent to indiscriminately bombard the Gaza Strip.

- Israel’s right to self-defence does not give it the right to indiscriminately kill Palestinian civilians, deprive the population of Gaza of the basic necessities of life, and forcibly transfer Gazans from their homes. These are not legitimate acts of self-defence. These are acts of collective punishment. These are clear violations of international humanitarian law. These are war crimes.

- IHL prohibits attacks that fail to discriminate between combatants and civilians, or would be expected to cause disproportionate harm to a civilian population and/or civilian infrastructure compared to the military objective. The scale of Israel’s military assault on Gaza and the unfathomable numbers of civilians killed, including thousands of children, belie any proportionality.

- IHL requires parties to give “effective advance warning” where an attack may affect the civilian population. If civilians are not able to move to an area that is safer, this will not be an effective warning. Irrespective of any warning Israel is still subject to its obligation to protect civilians. There is nowhere safe for Gazan civilians to go. They cannot leave the territory and the places where they have sought refuge, including in places protected under international law,[9] have been bombed.

- Parties to armed conflict must not forcibly transfer the civilian population of an occupied territory, unless the civilian security or military imperatives require it on a temporary basis. The permanent displacement of Gaza’s civilian population by Israel is a war crime. It represents the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their land.

- Israel’s actions in cutting off access to humanitarian aid are a form of collective punishment of the people of Gaza, which is prohibited by IHL. Israel, as the occupying power with effective control over Gaza through its blockade, has an obligation under IHL to ensure the basic needs and safety of the population of Gaza are met, including the provision of food and water.

- Other states have obligations to support the implementation of IHL. Each state should encourage its allies to fulfil their responsibilities to utilise the frameworks of IHL, including through sanctions, as provided by the Geneva Conventions. States, whether engaged in the conflict or not, must take all possible steps to ensure the rules of IHL are respected.[10]

- In the context of Israel’s flagrant and longstanding disregard for international law, including IHL and fundamental human rights, countries providing military aid to Israel (particularly the United States which provides over 3 billion USD in military aid to Israel each year) are actively facilitating Israel’s war crimes against Palestinians.

- Ongoing violations of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territories are also being exacerbated. Israel currently holds over 5000 Palestinian political prisoners in military jails, 170 of these prisoners are children (under 18 years) and over 1200 are administrative detainees. See more detail on pre-October 7 prisoners here, and detail on child prisoners here.

- Every year hundreds of Palestinian children under the age of 18 are arrested, interrogated and detained by the Israeli army and prosecuted in Israeli military courts, without the basic fair trial rights afforded to Israeli children under the civilian criminal justice system. The most common charge children face is throwing stones, which is punishable under military law by up to 20 years in prison.[11] Palestinian child detainees face physical and psychological violence at the hands of Israeli forces, and are routinely held in solitary confinement for interrogation. Israel’s practices are contrary to international law and human rights, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[12]

- Administrative detainees are prisoners who may be held by Israeli forces indefinitely on the basis of secret information, without being charged or facing trial. While the military court issues administrative detention orders for a maximum period of six months, these orders can be renewed for an unlimited period of time. The use of administrative detention in a widespread and systematic way is prohibited by international law but is used by the Israeli occupation forces as a means to punish and repress resistance to the occupation, including by human rights activists, students, lawyers and many other Palestinian civilians. Apart from being denied rights to a fair trial, Palestinians in administrative detention face severe restrictions on their rights, including their rights to communicate with family and receive visits, and adequate medical treatment.[13]

- More broadly, human rights groups have documented the systematic use of physical and psychological torture, and degrading and inhumane treatment by the Israeli occupation against Palestinian prisoners and detainees, contrary to its prohibition under international law.[14]

- Those who commit war crimes and those responsible for ordering, assisting or facilitating a war crime, are criminally liable. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has jurisdiction to adjudicate war crimes committed in or from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The ICC can only function when its work is supported by states.

- Palestinians’ right to self-determination and statehood is non-negotiable and fundamental to any prospect of a peaceful, political rather than military resolution to the situation in Israel / Palestine. Apart from ignoring the right of Palestinian people to determine for themselves what a just resolution might be, statelessness perpetuates the asymmetry between the negotiating parties. Israel enjoys sovereignty over its territory, Western diplomatic and economic support and controls the most powerful military force in the Middle East. Palestinians are stateless, oppressed, occupied and under the constant surveillance of the Israeli occupation forces.

- Currently 138 of 193 United Nations member states recognise the state of Palestine, including Iceland, Sweden, South Africa, India, China, Chile and Argentina. The criteria for statehood under international law are that a state should possess a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states.[15] Many experts agree that Palestine meets these criteria for statehood.[16] The commonest arguments against recognising Palestinian statehood rely on circumstances resulting directly from Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine. It is unfair and illogical to denounce Israel’s occupation and settlement expansion as breaches of international law yet, at the same time, to use the effects of those breaches on the Palestinians and the control of their land as an argument against recognition of Palestinian statehood.

- Under international law, refugees have the right to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced. For the 75 years since the Nakba - the mass expulsion of Palestinians from their lands - millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants have not been able to return, and Palestinians have faced further forced displacement and dispossession, including through the expansion of illegal Israeli settlements on Palestinian land, evictions and home demolitions. Over the last 75 years, the United Nations General Assembly and Security Council have repeatedly called on Israel to facilitate the return of Palestinian refugees. For 75 years Israel has denied Palestinians this right and forced them to live in exile.

- Realising the right of refugees to return is critical to any political solution to the situation in Israel and Palestine that respects Palestinian self-determination. As articulated by United Nations Special Rapporteurs: “The right of return constitutes a fundamental pillar of the Palestinian people's right to self-determination. The fragmentation of the Palestinian people, both geographically and politically, through administrative methods of control based on residency and race, tantamount to apartheid, has obstructed the realisation of the right to return and self-determination.”[17]

Citations

[1]“...occupation when a state has effective control, without consent, of a territory over which it has no sovereign title, such as the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory.”: How Does International Humanitarian Law Apply in Israel and Gaza? | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

[4] How Does International Humanitarian Law Apply in Israel and Gaza? | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

[5] Amnesty International report: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2022/02/israels-system-of-apartheid/#:~:text=This%20is%20apartheid.,order%20to%20benefit%20Jewish%20Israelis

Human Rights Watch report: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/27/threshold-crossed/israeli-authorities-and-crimes-apartheid-and-persecution

B'tselem report: https://www.btselem.org/publications/fulltext/202101_this_is_apartheid; and Special Rapporteur report: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G22/448/72/PDF/G2244872.pdf?OpenElement

[7] How Does International Humanitarian Law Apply in Israel and Gaza? | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

[8] How Does International Humanitarian Law Apply in Israel and Gaza? | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

[9] International Humanitarian Law Databases: Rule 35 | ICRC

[10] Common Article 1 of the Geneva Conventions: Common Article 1 of the Geneva Conventions revisited: Protecting collective interests - ICRC; https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S0020860400073058a.pdf

[11] Children | Addameer

[12] Military Detention | Defense for Children Palestine (dci-palestine.org)

[13] Administrative Detainees | Addameer

[15] Montevideo Convention of 1933, art 1.

[16] See, for example, Boyle, F. A. (1987). Creating the state of Palestine. The Palestine Yearbook of International Law, 4(1), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.1163/221161488X00025

Panganiban, S. K. (2016). Palestinian statehood: A study of statehood through the lens of the Montevideo Convention [Master’s Thesis, Virginia Tech]. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/64512

Pitta, M. (2018). Statehood and recognition: The case of Palestine [Master’s Thesis, University of Barcelona]. https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/123175/1/TFM_Michele_Pitta.pdf

Quigley, J. (2010). The statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict. Cambridge University Press. https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/42481#:~:text=The%20book%20is%20the%20most,Zionist%20and%20other%20imperialist%20forces

Whitbeck, J. V. (2011). The State of Palestine Exists. Middle East Policy, 18(2), 62-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4967.2011.00485.x