12 years old

August 31, 2005

A modest public school, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

The last school bell rings. You hear Tanggal 31 Ogos by Sudirman being played on the school speakers—a song painfully familiar to you. You pay no attention to it as you rush home to do absolutely nothing but watch TV. The song is played on the anniversary of Malaysia’s independence from British colonial rule in 1957. But you think, “Who cares?” Unbeknownst to you, the trojan horse of American shows is colonising your mind with Eurocentric images of people. You then wonder, “Why doesn’t anyone on Lizzie McGuire look like me?”

You haven’t struggled with this idea of race much in the lush Malaysian garden of multiculturalism. You’re ethnically Chinese, of Malaysian culture, with English as a tour de force spoken in the household. Your Malay- and Indian-identifying friends look different to you, but it’s a sight you’ve always seen. You think, “They just look like that because they just do!” This outward difference did not matter anyway; you were too pre-occupied with trying to get as many people as possible to like you.

16 years old

2009

A semi-private, rugby-centric, all-boys high school, Auckland, New Zealand.

Thanks to your middle-class privilege, you get a one-way ticket to New Zealand for education—do not pass go. At last, an exciting new start to school life you thought would be like Lizzie McGuire.

Unfortunately, you now struggle with this idea of race and identity.

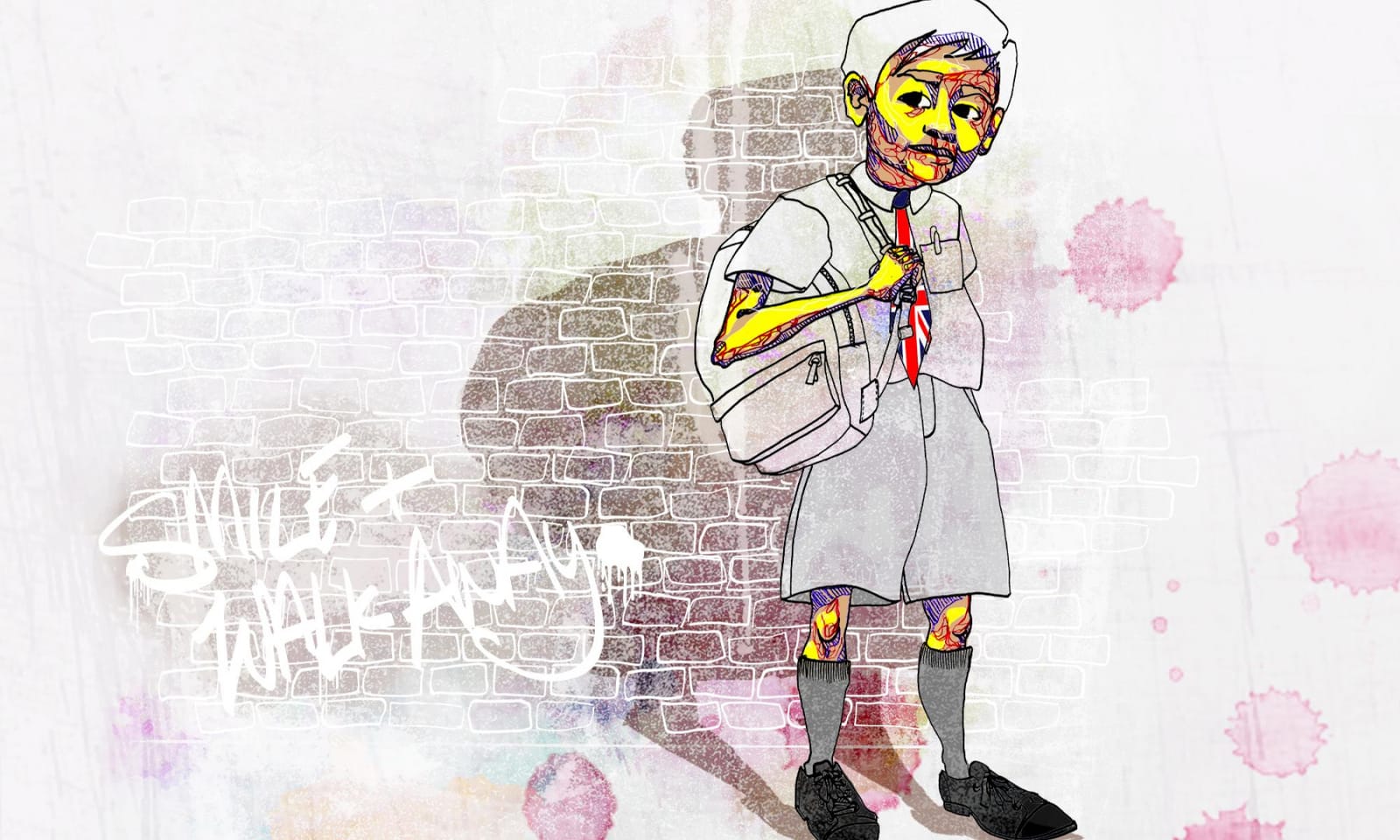

What was once unquestionable and unshakable has now become a source of anxiety for you. “I am just like them!” you tell yourself in your British system of school uniform. How ironic, have you been colonised again?

You learn the fundamentals of genes in Ms Woollards’ biology class. Genes are akin to architectural blueprints that dictate how a building is built. In biology, these “architectural blueprints” are referred to as genotypes, while the observable “buildings” are called phenotypes.

Case in point: the colour, or phenotype, of a pink rose. The “red” pigment gene from one plant plus the “white” pigment gene from another plant creates pink flowers. Sometimes, if the “red” pigment gene is stronger than the “white” pigment gene, the flowers will remain red. In other instances, the “white” pigment gene may become stronger than the “red” pigment gene due to environmental conditions, which results in white flowers. Overall, you think that this is a confusing molecular boxing match and you are ready for the knock-out.

As an aside, someone will eventually tell you pink is the only colour that has an actual name when a colour (red) is diluted with white. Blue diluted with white is light blue and not “blink”. Challenge them by saying grey.

As you try and rationalise how you look compared to your mostly White (or White-presenting) peers, you classify the observable differences as phenotypic differences. These differences include, but are not limited to, skin colour, eye shapes and hair texture. “How did these differences come about?” you wonder during your lunch break. Well, your older self has answers, but first, you go for a walk to find a cool spot away from everyone else.

Rather than being made up of two genes, like the pink rose, there are 170 genes involved in human skin colour. Of these 170 genes, there are 11 to 14 genes co-involved in the production of melanin, a light-absorbing pigment that gives skin “colour”. With the multiple combinations possible, it is clear that the pink rose analogy suddenly gets a little thorny. I wonder if humour is hereditary?

In fact, there are other genes involved in the other phenotypic differences we observe such as eye colour, height, and hair texture. However, these genes make up a small percentage of genes that are variable between humans. Interestingly, you are 99.9 percent related to every school boy you had a crush on.

You look down at your own skin bearing signs of a sunny summer. This increase in melanin production in your skin is in response to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Having more melanin in your skin protects you from UV radiation. Interestingly, you also learnt at school that the direct ancestors of humans were very likely dark-skinned. UV radiation is not noticeable to the human eye and is the most concentrated around the equator. UV radiation can penetrate through skin and destroy folate, which is a key chemical involved in DNA synthesis. Importantly, DNA is the genetic “language” that dictates every biological process in our body and DNA synthesis is a process in which DNA is replicated so that this language is passed on to the next generation. This process of DNA synthesis occurs at a much higher rate during pregnancy. If folate is destroyed by UV radiation, this would impair DNA synthesis and cause potentially fatal birth defects. Therefore, there is a 'selective advantage' by having darker skin (i.e. more melanin) in these areas of high UV radiation such that adequate folate is maintained during pregnancy.

“How did I lose pigmentation in my skin then?” you question while you quickly find some shade from the scorching New Zealand sun. Migration of modern humans to various regions across the globe resulted in a different type of selective advantage in the form of having less skin pigmentation. The further you are from the equator, the less UV radiation your skin is exposed to. Having less skin pigmentation in geographical areas of low UV radiation allows for the efficient conversion of cholesterol into vitamin D, which is vital to bone health. In contrast, having high skin pigmentation in areas of low UV radiation would be detrimental to vitamin D production due to excessive absorption of UV radiation. Then, you think about all the misogynistic jokes said by the boys in high school about giving the “D” in vitamin D. You cringe. Have we really evolved to this level?

The school bell rings, and it is the end of the lunch break. You file into your respective classroom, pull your sock garters up and instantly get a strong whiff of sunscreen throughout the hot sticky class. You look over and someone has a tan line of something derogatory spelt out with sunscreen. Wonderful.

“It wasn’t the norm to apply sunscreen in Malaysia anyway, so what’s the big deal here?”, a pressing question you had during your indoctrination to formal English grammar.

Reality suddenly crashes down on you with a booming shout.

“Ng, what is a pronoun?” asks the teacher.

“I, I don’t know sir…” you stutter back, clearly too shy and caught off guard to really speak your mind. You did know the answer! It doesn’t matter, no one expects anything of you as an Asian international student in this English class.

To go back to your pertinent question of why Sunscreen No.5 was so prevalent, you have to understand that Australia and New Zealand have the highest incidence of skin cancer in the world. You also need to understand the concept of 'displaced genotypes'. This idea of displaced genotypes occurs when genotypes are maladapted to new environmental stressors. In this instance, the relatively recent migration of Europeans to Australia and New Zealand has resulted in a dissonance between genotype and environment. In contrast to Europe, Australia and New Zealand have much higher UV radiation. Hence, these populations are at a higher risk of skin cancer compared to populations with more skin pigmentation.

Suddenly, a slurry of “he, she, me, I, they…” echoes through the classroom to answer the question. You embarrassingly sink your head and the class continues on. Better luck next time, Jin.

25 years old

2018

Some random party, Auckland, New Zealand

You are at a point where you embrace your racial identity but still stumble when trying to describe your cultural identity.

“Where are you from?” someone drunkenly asks.

“Well, I spent half my life in Malaysia and half in New Zealand, so I guess Kiwi-Malaysian?” you reply knowing this would be the last thing you say before leaving the conversation.

“I’ve been to Malaysia!” they interject before you turn your back.

“Where specifically?” you ask with piqued interest.

“Oh, I was in transit. I would’ve preferred a transit in Singapore though! That airport is meant to be the best!” they retorted while fisting the air with their drink to the beat of the music.

You smile and walk away.

27 years old

2020

Reece’s lounge at 583, Melbourne, Australia.

One pandemic and many critical self-love lessons down, you have found an appreciation and understanding for the gamut of phenotypic differences. Despite biology showing that we have more in common with one another than we think, you wonder why we fall back on this social construct of race. Even though you look different to the majority of your peers, genetically speaking, your genomes are about 99.9 percent similar. Why was your experience so different to the “majority”? In some ways, you are like “them” in many ways. But what sets everyone apart is their personal journey through life. For a large proportion of some, these journeys are coloured by systems that uphold a bias towards this idea of race. What we can do together is engage in dialogue and dismantle these systems. Some might say your job isn’t to educate. However, you’ve learnt to give the benefit of the doubt, or rather, the benefit of being inquisitive, to everyone wanting to engage on this topic.

You rewatch the Lizzie McGuire biopic of her tales in Rome as an adult in isolation.

“Wow, I really identify with the 99.9 percent of Lizzie McGuire here,” you say to yourself as you sink deeper into the hole of cynicism and benevolence.