When voices are excluded from Aotearoa’s media, it undermines the inclusive ideal of democratic participation. This story documents the suppression of Palestinian New Zealanders’ speech and speech about Palestinian rights. Incidents of suppression play out differently in private or public media and space because the accountabilities of public and private entities differ.

Merely documenting the inequality says nothing about the experience of having one’s identity sidelined and reduced to politics. Therefore, once the stage is set, the story belongs to Palestinians. Four Palestinian New Zealanders spoke with The Lovepost about their modes of expression and activism. They pursue their rights through grassroots outreach and advocacy organising, social media, and the arts. They, like international Palestinian intellectuals, speak about old media and new alternatives—indeed, a generationally new understanding of solidarity—and they encourage others to proactively educate themselves.

Documenting the disappearance

It seems counter-intuitive that the narrative of the occupying state of Israel should take precedence over the voices and experiences of the occupied Palestinian people. Dr Rand Hazou, senior lecturer at Massey University and a Palestinian New Zealander, provides some history:

"Edward Said, the Palestinian American scholar, often talked about how the Palestinian narrative is often just a footnote to the Zionist narrative.

"After the atrocities of the Second World War, there was a real, driving need to centre the Zionist narrative to ensure that those atrocities never happened again—and fair enough. That discourse was also one of the guiding reasons behind the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, something that I firmly believe in.

"But it still has produced this effect of the political discourse that often makes invisible the personal narratives of Palestinians and their history."

While Israel has become a regional superpower conducting an occupation that the United Nations Human Rights Council considers illegal, the Zionist-centred postwar response has not evolved. Instead, it has calcified into a media norm. Below are three documented examples of the intentional, specific exclusion of Palestinian stories from New Zealand media or political participation.

Public media and the heckler's veto

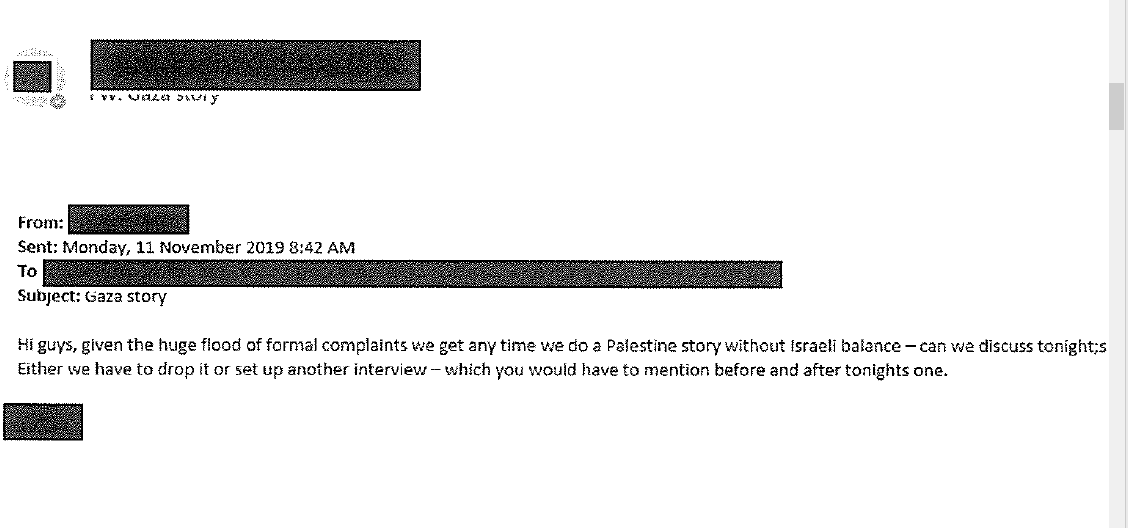

My own book Still Lives—a memoir of my four years of work in Gaza—launched on TVNZ’s Breakfast show in November 2019. Radio New Zealand (RNZ) was to follow. When RNZ promoted and then abruptly cancelled the interview, I asked for their reason. None was forthcoming, so I filed an Official Information Act (OIA) request. Radio New Zealand disclosed this internal email:

An RNZ journalist familiar with the events said at the time:

"As I understand [it] someone got in touch with the head of radio when they heard your interview promo-ed and complained.

"There’s a real reluctance among a lot of the presenters to interview people on the [Palestine-Israel] conflict because they know the amount of criticism it generates—from both sides but the pressure from the Zionist lobby is, I think, well in excess of that from pro-Palestinian groups.

"The idea that your book didn’t result in an RNZ interview I find astounding. I’ve tried to think of possible parallels. A Han Chinese [writer] living in New Zealand who spent time in Xinjiang and had intimate knowledge of the [Uyghur] concentration camps is the closest I can come up with. We’d be falling over ourselves to get them on radio."

RNZ is not the only media outlet to avoid the issue of Palestine, but because it is publicly funded, RNZ is required to disclose information in response to OIA requests.

Private media: editorial gatekeeping

What lies behind the media’s avoidance of Palestine? The Lovepost spoke with a journalist in another New Zealand news media company whose writing “rebalances and prioritises voices that have previously been excluded or under-represented.”

Noticing the lack of reporting on a 2023 Palestine statehood petition, they “wondered why New Zealanders tended not to know much about what is happening between Israel and Palestine and why there was a sense of nervousness for people to have an opinion.” After doing some research, they understood that voices that supported Palestinian statehood "were often shut down and threatened."

"I tried to understand why this was," they said. "I wanted to try to bring these voices into mainstream consciousness in the least inflammatory way. When I first brought this to the [editorial] table, I was warned to talk to community leaders with caution."

The journalist researched and wrote a story about the statehood petition that would “tell a Palestinian human rights issue through Palestinian voices and voices of supporters, without taking an adversarial approach.” When the story was ready to publish, “all input from Justice for Palestine [a Palestinian-led advocacy organisation], a supporter of the petition who is Jewish, and an anonymous Palestinian citizen were omitted at the advice of my editor.”

Editors explained that they had significantly altered the story because they were certain the company would face a flood of hostile feedback, and at worst, that publication might endanger the safety of those involved. The journalist emphasised that this editorial timidity is specific to the issue of Palestine: “[W]e’ve never avoided unwanted responses by not publishing something that isn’t offensive and stands within editorial guidelines” on other issues.

Public space: whose feelings count?

Assembly and protest are essential—and, one wants to think, available—forms of democratic expression and participation. Palestinian New Zealanders cannot assume such access.

On 11 May 2022, Al Jazeera’s Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was shot in the head while she was wearing a helmet and vest marked ‘PRESS’. Abu Akleh was killed while reporting in the West Bank. Israel refused to cooperate with investigations by the media and the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation. Many of the findings are summarised in this interactive forensic architecture investigation. It concludes that Abu Akleh was intentionally targeted and "after being shot, Shireen was actively and deliberately denied medical aid” by the Israeli armed forces in an “extrajudicial killing”. Her murder has been referred to the International Criminal Court. A violent assault on Abu Akleh’s funeral procession by uniformed Israeli forces further stoked outrage in Aotearoa and around the world.

May 15 is Nakba Day, the day on which Palestinians commemorate the catastrophe or ‘Nakba’ of their expulsion and dispossession in 1948. In the run-up to Nakba Day 2022, Wellington Mayor Andy Foster was advised by the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) to disallow a Palestinian display of their national colours on the Michael Fowler Centre for Nakba Day, although the display had already been approved. MFAT advised that “displaying the Palestinian colours could result in complaints from the Israeli ambassador and other Israeli groups.”

Auckland and Christchurch permitted Nakba Day events to proceed despite receiving the same advice from MFAT. Wellington did not, although Ukrainian national colours had previously been displayed on the Michael Fowler Centre without similar concern for the Russian ambassador’s sensitivities. The Israeli ambassador is a guest in Aotearoa, not a policy maker, and the “other Israeli groups” whose feelings took precedence over New Zealanders’ right to peaceful expression have never been identified.

Again, the mere prospect of Israeli or Zionist New Zealanders’ discomfort was enough to problematise and pre-empt peaceful Palestinian public expression. Wellington was one of only two major cities in the West to prevent Nakba Day commemorations this way.

Because this exclusion took place in the public sphere, Wellingtonians and international solidarity groups could and did protest loudly (and vividly, with a guerilla projection of the Palestinian flag on the walls of the Te Papa Museum). Official Information Act requests probed the erosion of Palestinians’ right to participate in Wellington’s public life.

In due course, MFAT reviewed and revised its policy. “Future responses from the ministry will be limited to providing New Zealand’s international policy settings on an issue,” said MFAT secretary Julie-Anne Lee.

Being Palestinian in New Zealand is a “layered trauma”

Such gatekeeping must be documented so that the need for change can be understood. Yet the gatekeeping is scenery, not plot. It is against that backdrop that Palestinians live the real story of contingent participation in the public life of Aotearoa.

The four Palestinian New Zealanders who shared their stories with The Lovepost each respond very differently to exclusion. However, in common, they have formulated a theory of change and staked out a role by which to pursue change. They make it clear that a suppressed voice does not fall silent.

Being Palestinian also implies that one is a Middle Eastern person of colour, presumed Muslim (although not all Palestinians are Muslim), and tauiwi (non-Māori) with roots in the resistance to the modern world’s longest military occupation. To carry that complex identity every day through the streets of New Zealand is a “layered trauma”, says Bassma*, an extrovert in her twenties. She introduces herself to strangers as a Muslim-Arab New Zealander.

"I don’t use the word ‘Palestinian’, because being Palestinian inherently is political," Bassma says. "You don’t know if it’s going to impact your job or your family, or your own safety. So generally I don’t tell them. It’s not safe otherwise, to be honest.

"Someone actually told me, ‘I wish Palestinians would stop fighting back.’ I told her, ‘As a mother you don’t know what you would do. You wouldn’t stay quiet if someone was hurting your children.’ When you say you’re Palestinian, it creates a backlash sometimes."

Tameem Shaltoni, in his late thirties with two school-aged children, also speaks of professional risk when one is identified as Palestinian. Shaltoni’s family was dispossessed from Al-Lidd (Lydda), Palestine to Gaza, and then again to Jordan in the Nakba of 1948. There, Shaltoni says “I lived my entire life within communities of Palestinians who all shared more or less similar experiences and stories of dispossession and occupation.” As an adult immigrant to Aotearoa, “I began to get exposed to people who denied my identity and history and even advocated for further oppression and denial of my rights and those of my people.”

The sense of having their identity denied is shared by each of the Palestinian speakers.

“I could say that it makes me angry,” says Nadia Abu-Shanab, a few years younger than Shaltoni with two pre-schoolers. “But more than anything, I think underneath that anger is a kind of grief that the articulation we might have doesn’t get to breathe. It doesn’t get to see the sunlight. It doesn’t get to move through the world.”

Invisibility can also be internalised. Dr Rand Hazou, the eldest of the speakers at 48, works at the intersection of the arts and social justice. He recalls researching a theatre project with his father. Each time his father looked back over his own life, his story repeatedly strayed: "The politics and the history, and the dates would come in," Hazou explains. "A lot of our history and identities is a history by numbers: [the Nakba of] 1948, [extended occupation following the war of] 1967, etc. Even within Palestinian communities, we’ve got this issue: how do we speak and not be constrained? [How can we] be seen as real human beings rather than just as members of a political community—one often defined by the other?

When the New Zealand media do cover Palestine stories, they perpetuate Israel-centred definitions. The events of a particular day are decontextualised. By avoiding political analysis and reporting in the present tense, the media robs audiences of the cause, motive and flow of events—the setting that underlies and gives shape to the events of that particular day. Because it has been depoliticised, the action of any one day feels inexplicable.

Palestinians must navigate this present-tense reporting when the opportunity arises, as it did in 2017. The global Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign seeks to apply peaceful economic pressure on Israel until Palestinians’ equal rights are realised, including by means of cultural boycotts. Within that campaign Nadia Abu-Shanab and Justine Sachs (a Jewish fellow trade unionist) wrote a letter to the artist Lorde, asking her not to perform in Israel. Lorde cancelled her performance. Suddenly Abu-Shanab and Sachs had the world’s major newspapers on their phones. A human rights-based global campaign had laid the groundwork for Lorde to listen, but that was not the story that the papers were lining up to publish.

“I hated it.” Abu-Shanab grimaces. "The reason that Lorde cancelled was that thousands of people had been building movements over generations that slowly shifted the dial to a point where it became . . . for her as a young, progressive artist, culturally untenable . . . to go and perform in Israel.

"And what happened when the story came out was this very individualised . . . ‘Oh, two women write a letter and someone changes their mind.’ But that was the opportunity we had."

Abu-Shanab lives by that theory of change, as a unionist and as a founder of Justice for Palestine.

"I’ve always had a recognition that [change requires] organisational work," Abu-Shanab says. "It’s that slow, deep, unglamorous, often unseen kind of work . . . a deeper, more relational work where people come together and decide to try to thread the needle on moving people in our communities toward a better position on Palestine.

"The work we do together is not that self-reinforcing echo chamber. We have to be able to break through to that group of people who are unsure, undecided, haven’t been exposed, have questions, are curious or maybe have a completely different political training."

Tameem Shaltoni felt “spoken over and about” in the same advocacy sphere. Although he is an expressive writer, he quickly found himself thwarted by the major media’s gatekeepers. He responds by writing on social media and blogs—a path that feels both “liberating” and “harsh”. His writing is often met with aggression, abuse and denial. "[In addition] and most impactful to me, [with writing] comes a high emotional toll when we open up on intergenerational traumas and not only relive them but also dwell on them [to make others understand]," Shaltoni says.

At times, Shaltoni’s written voice boils with anger. He makes no apology; rather, he writes to require others to hear uncensored Palestinian emotions.

"My writing is a response to being excluded and denied my rights and my identity," Shaltoni says. "I write to resist and to exist. Expressing myself and how I feel is not a byproduct of a story I am telling; it is the story. My voice can feel filled with anger and rage, because that is how it feels to be dispossessed and oppressed."

Dr Hazou’s theatrical work creates a performance and a channel for cathartic expression. When he develops theatre pieces with marginalised participants (whether they are Palestinians, social welfare recipients or prisoners), does he have a political objective, or is expression its own story?

“It’s thinking about theatre as a catalyst for some kind of social change," Dr Hazou says. So in that sense, there’s a kind of radical potential there. There’s a political imperative.” However, for Hazou, giving people a voice is not sufficient to realise that imperative.

"[Expression] can enhance a sense of dignity for communities or people that have experienced different types of invisibility or disenfranchisement," Hazour says. "But if they’re speaking and no one’s listening, then what’s the point? So the other part of the equation is to think about how power works and create opportunities for power to listen."

Each of these modes of activism is about speaking on one’s own terms: the monopoly of old media and unbalanced set-piece events is over. Those channels de-politicise the audience's understanding, and that stance no longer suffices. Tareq Baconi, an international Palestinian analyst and author, recently declined to speak at Rice University’s Baker Institute's "Israel at 75" conference as the token Palestinian voice, dissenting on the periphery of a panel of Zionists. He wrote a strong argument that opportunities to speak should be rejected if they merely reproduce the existing power disparities.

How do New Zealand Palestinians create exchanges where they speak on their own terms about their individual and collective rights? Where are the excluded voices heard? The answers reflect an evolving understanding of solidarity—of the role that non-Palestinians can play in supporting Palestinians’ own pursuit of justice.

Generational perspectives

Former refugee-immigrant communities can be thought of in generations, not only of age but of belonging. The passage from trauma to a new, more integrated normalcy takes time. The passage is audible: the fresh pain of Shaltoni’s voice differs from the sound of Abu-Shanab’s professional organising, and speaks to the value of Hazou’s project of theatrical expression.

Hazou points to the gradual accumulation of Palestinian capacity and means of advocacy. He says that among “any refugee group, a lot of effort has gone into trying to fit in and trying to rebuild lives . . . making sure you’ve got work, building up your life again."

"But now, we have a second, third generation who are taking up community and political life more fully and confidently," he continues. "As part of their participation, Palestinians are establishing all kinds of well-rounded community presence including advocacy relationships with editors and politicians."

Within his own advocacy, Hazou pursues a politics of inclusive solutions:

"The way forward for me, and I’d hope with my Jewish brothers and sisters, is to insist on things like human rights. [The] idea that they’re universal and inalienable—there’s that principle of inclusion that I think is really important, that insisting on my rights doesn’t necessarily mean that another group’s rights are going to be taken away. That’s the way out, to just firmly insist on human rights as a way forward."

Abu-Shanab regards the role and potential of rights differently. “I try to avoid legalistic solutions to things that I think people can solve together," she says in relation her union work. "But I also understand the law as a good tool. Human rights are one such tool. It is not likely to be a sufficient tool on its own, given “its roots in some parts of the world that really shouldn’t be outsourcing their ideas on how to treat people.”

Abu-Shanab also enjoys the flowering of new media where Palestinian voices are now being actively sought out. “In the long shadow of the war on terror, there were a lot of young Arabs . . . [who] started creating their own media. And I think that’s a real cultural force,” she says.

New media, the arts and personal encounters disintermediate the old media’s curation. In these new spaces, Palestinians can humanise politics and state their case personally

A “believer in grassroots education”, Bassma is emphatic that Palestinian stories are being told “in the street, in your neighbour’s house, in community meetings and cultural events that you organise."

"It’s not just media that gives us a voice and that’s the Palestinian challenge," Bassma says. "I don’t think of this [method] as weakness. I view this as enriching.”

To find the voices that are suppressed (and those include many groups in addition to Palestinians), the onus is on individuals to seek out opportunities to listen. In Bassma’s words:

"Branch out beyond your own circles and your own social media platforms that are formulated by Artificial Intelligence to give you information that you constantly, regularly look at. You need to engage with people you wouldn’t otherwise engage with, be curious, be respectful. It’s all about persistence and hopefulness. To shine light on the Palestinian cause is to shine light everywhere."

*Some names have been changed to protect the identity of subjects.